TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — Officials on Thursday stepped up emergency relief efforts after the fiercest band of tornadoes in decades tore a gaping wound through Alabama and at least five other Southern states, causing hundreds of deaths and a wide band of destruction.

“”This may be the worst natural disaster in Alabama’s history,”” Gov. Robert Bentley told reporters during a day when his state’s death toll began in the dozens and quickly rose to at least 180. With the loss of life reported in Mississippi, Tennessee, Georgia, Virginia and Kentucky, the toll stood at about 270 by mid-afternoon.

“”We do expect that number to rise,”” Bentley said at a morning news conference where he and other officials were careful not to predict the final death toll. “”We’re sure it will.””

Craig Fugate, administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, pledged aid to the region where each state was handling its own search and rescue efforts. Fugate traveled to Alabama in the afternoon and his boss, President Barack Obama, will visit the state Friday to meet with officials and victims, the White House said.

Speaking at the White House before he announced the details of his new national security team, Obama acknowledged the storms, which he called “”heartbreaking, especially in Alabama.””

“”In a matter of hours these deadly tornadoes, some the worst that we’ve seen in decades, took mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, friends and neighbors even entire communities,”” Obama said.

“”We can’t control when or where a terrible storm will strike, but we can control how we respond to it,”” the president said. “”I want every American who has been affected by this disaster to know that the federal government will do everything we can to help you recover, and we will stand with you as you rebuild.””

Obama said he has talked with various governors to tell them the government “”was ready to help in any possible way.””

Obama declared a state of emergency in Alabama, clearing the way for federal aid. Meanwhile, 1,500 National Guard troops rushed to the scenes of destruction. Firefighters, police and paramedics probed piles of debris as dogs sniffed for the scent of survivors. The number of injured was in the hundreds and no one had an accurate count of the missing in a swath of damage that was more than 60 miles long and up to half a mile wide.

It was too soon to begin computing the dollars and cents of the damage, but the disaster will likely take weeks and months to repair, officials estimated. Meanwhile, water, clothes, electricity and shelter were the immediate concerns.

Bentley said that between half a million and 1 million people in Alabama were without electricity and that there were numerous injuries, especially in Tuscaloosa, which seems to be among the hardest-hit areas in the state. A nuclear power plant was shut down in Alabama but officials said there was no danger of radiation leakage.

Bentley said that he had relatives in Tuscaloosa who had survived the storm’s onslaught.

“”The family came through OK,”” he told reporters, “”but I’m concerned with everyone’s family.””

The extent of the current toll was difficult to confirm, and officials were careful to avoid citing a specific number while rescue efforts were under way in individual states. But so far, Mississippi officials reported 33 dead, Tennessee raised its report to 33, Georgia reported 13, Virginia said it had eight deaths and Kentucky reported at least one death.

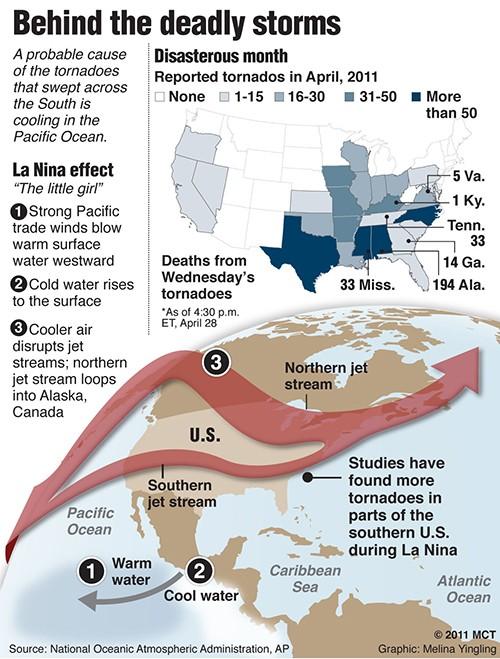

The latest storm began Wednesday afternoon. The National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Okla., said it received 137 reports of tornadoes.

Bentley said Alabama residents were prepared for the storms, but the violent weather moved into the region too quickly and forcefully to make evacuation effective.

“”It was just the force of the storm,”” the governor told reporters. “”It’s hard to move that many people.””

Officials estimate the intensity of the storm at F4 or F5, meaning winds in excess of 150 mph and as deadly as 200 mph. Whole neighborhoods were flattened.

Police and other emergency services in Tuscaloosa, a city of more than 83,000 and home to the University of Alabama, were devastated, Mayor Walter Maddox said. At least 36 people were reported dead and more than 600 injured.

“”I don’t know how anyone survived,”” Maddox told reporters. “”We’re used to tornadoes here in Tuscaloosa. It’s part of growing up. But when you look at this path of destruction that’s likely 5 to 7 miles long in an area a half-mile wide to a mile wide, I don’t know how anyone survived. It’s an amazing scene. There are parts of this city I don’t recognize, and that’s someone that’s lived here his entire life.””

At a news conference at Tuscaloosa City Hall, Maddox, who had just toured his city by air, said some neighborhoods had been “”removed from the map.”” The devastation crossed the city’s economic lines, from middle-class housing for University of Alabama students and employees to one of the city’s oldest public-housing complexes.

Officials were in an urgent phase of search and rescue, digging for bodies and trying to account for everyone. But the task was made more difficult because a key city building that housed the emergency management agency had been destroyed. So had most of the city’s trash-pickup fleet. Two major water tanks were empty, Maddox said, and the city was facing potential shortages. He urged conservation.

“”This is going to be a very long process,”” he said. “”The amount of damage that is seen is beyond a nightmare. … This will not be an easy journey. We ask for patience and we ask for prayers.””

One of the worst neighborhoods was Cedar Crest, a collection of modest single-family houses near the university, home to many campus workers, professors and students and surrounded by strip malls, stores and fast-food restaurants. On Thursday morning, much of it was closed to cars, but throngs of people walked the streets — rescue personnel, gawkers, college students in running shoes and fraternity and sorority T-shirts.

The devastation was unavoidable and widespread. Trees were uprooted and broken on the ground, a gasoline station twisted into an accidental version of a Gehry building made of sheet metal, the drug store gutted and a mattress store turned into a hulking, filthy ruin. Block after block of homes were turned into skeletons with nothing but walls as silent sentries.

On one street, a group of young people marveled at a large boxy appliance — it wasn’t quite clear what kind — suspended about 20 feet up in a tree. A Winnie the Pooh crib bumper hung from another tree, like a sad banner from an awful party.

Cars had been thrown around, their windows bashed in, their metal battered and caked with mud. A newish Chevy Avalanche pickup was clogged with chewed chunks of fiberboard, its “”door ajar”” signal bonging nonstop.

“”Dad, we’re at ground zero here, and it’s awful,”” a young man said, speaking into his cellphone. “”It’s really sad.””

Kirk Miller, 36, and his wife, Rachelle, 44, were standing outside of the custom four-bedroom home they built four years ago. One side of it had been caved in from the top, with much of the roof falling on their ski boat and Kirk’s motorcycle.

They felt, though, that they had escaped the worst: Kirk had been traveling on business Wednesday night, and Rachelle and their 3-year-old son, Wyatt, were alone when the tornado came. When she knew it was coming, she put Wyatt on his stomach in a windowless bathroom and covered him with her body. They made it. Their dogs made it.

When they walked outside, Rachelle said, she couldn’t believe what she saw. Wyatt said, “”Mommy, our house is broken.””

Kirk said he grew up in Alabama and that tornadoes were not an abstraction to him. He said that when he heard there had been some damage, he figured he’d see the usual — shingles strewn around, a few trees down.

But this time, he said, “”I just couldn’t believe it. All the trees were down. It’s just all gone. It ain’t Tuscaloosa anymore.””