WASHINGTON — While the ugly public fight in Congress over how to keep the government funded for the next few months is getting all the attention, behind the scenes a bipartisan effort to craft a long-term path to fiscal stability is proceeding slowly and quietly.

The immediate struggle to make spending cuts for fiscal 2011, which runs through Sept. 30, is getting most of the publicity amid fears that a partisan stalemate may lead to a government shutdown. The government will run out of money on March 18 unless a fiscal 2011 spending plan is adopted. Two Senate votes Wednesday are both expected to fail to resolve the issue, which will require high-level negotiations next week.

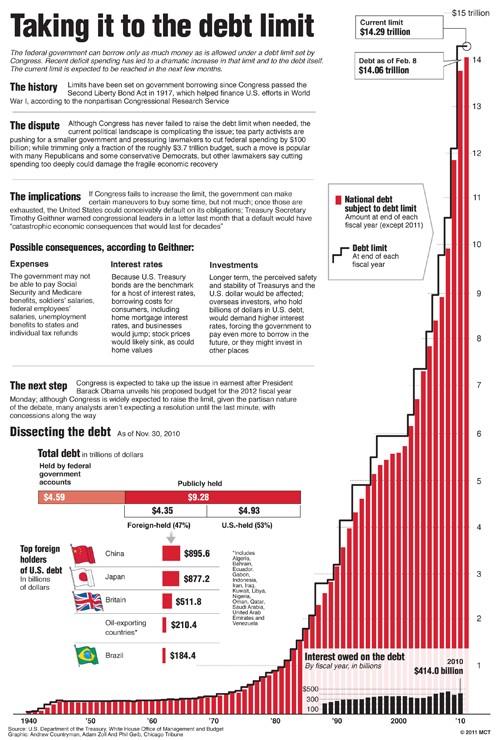

However, the short-term funding fight is simple compared to the real budget challenge, which is stark: The government borrows almost 40 cents of every dollar it spends. The White House projects a record $1.65 trillion deficit this fiscal year, and $7.2 trillion in deficits over the next 10 years.

President Barack Obama’s budget for fiscal 2012 would leave the government $26.35 trillion in debt after the next decade, up $12.8 trillion from last year. All the debt the nation ran up in history totaled only $5.6 trillion at the end of fiscal 2000.

The immediate fight over short-term government funding “”doesn’t deal with the real problem,”” said Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad, D-N.D. “”Debt is the threat.””

Unless major changes are made soon to federal tax and spending laws, “”interest costs for everything will rise, and rise rapidly,”” said Erskine Bowles, co-chairman of the bipartisan National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. That will make it harder to buy homes or cars, or to expand a business, or to reduce unemployment.

In December, Bowles’ commission outlined how to reduce deficits by $4 trillion over 10 years. Neither Obama nor lawmakers from either party have agreed so far to go along with its plan.

The chief hope for long-term debt reduction now rests with six senators, three from each party, who have been meeting privately once or twice a week. Leading the Senate effort are four commission members who backed its final report: Democrats Conrad and Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin of Illinois, and Republicans Tom Coburn of Oklahoma and Mike Crapo of Idaho. Also involved are Sens. Mark Warner, D-Va., and Saxby Chambliss, R-Ga. They are liaisons to a broader group of about 25 senators who’ve signaled interest in joining a serious bipartisan plan.

Some of them dined Monday at a Capitol Hill steakhouse with Bowles and his commission co-chairman, Alan Simpson. The group is trying to build on the commission’s blueprint.

They hope to propose a sweeping debt-reduction package of legislation this spring, and they hope that the Obama administration, which has supported their talks, will step in then and push for a big deal.

“”I don’t know yet how this will play out,”” Conrad said. “”First we have to demonstrate there’s resolve for a bipartisan group to come together.””

They won’t discuss specifics publicly yet, but Conrad said “”it has to be a comprehensive package”” likely including Medicare, Social Security, Medicaid, defense and taxes. All involve political peril, as cutting the costs of popular programs and raising tax revenues are necessary to solve the problem.

The deficit commission report, endorsed by 11 of its 18 members, recommended capping spending for almost all government programs except Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and some national security programs — and even they were to be overhauled.

The panel proposed revamping the nation’s tax system. Instead of five income tax rates, there would be three: 8, 14 and 23 percent. They’d also end or trim about $1.1 trillion in popular tax breaks, such as mortgage interest deductions.

Conrad recalled a conversation he had with Durbin before the commission vote in December. When Durbin asked how he would vote, Conrad said he’d vote yes, because “”the only thing worse than being for this is being against it.””

Impending circumstances may give the Senate negotiators momentum. The Treasury Department expects the federal debt limit, now $14.294 trillion, to be reached as soon as next month. Unless Congress raises the limit, the government will be unable to borrow, and could shut down. That prospect could quake global financial markets, which adds pressure on lawmakers to compromise.

There are no easy paths to ending federal deficits and taming the national debt. Republicans like to say that eliminating waste, fraud and abuse could make a serious dent in the deficit, but on Monday Douglas Elmendorf, the director of the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, put that into realistic perspective.

“”Fiscal policy cannot be put on a sustainable path just by eliminating waste and inefficiency,”” he said. “”The policy changes that are needed will significantly affect popular programs or people’s tax payments or both.””

That’s the long-term big picture, the one the six senators are talking about behind closed doors. For now however, in the open, lawmakers are talking only about how much to cut from non-military domestic discretionary programs — which total only 12 percent of the federal budget.

“”This whole process doesn’t make a lot of sense to me,”” said Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., “”and I’m afraid it doesn’t make sense to a lot of West Virginians or a lot of my fellow Americans.””

Beneath the surface, however, there’s one kernel of harmony that offers hope for eventual compromises that matter.

“”The entire conversation in Washington, D.C., has changed,”” said House Chief Deputy Whip Peter Roskam, R-Ill. “”Now the entire conversation, including the conversation with the Senate and the White House, is where are we going to save?””

———

(c) 2011, McClatchy-Tribune Information Services.