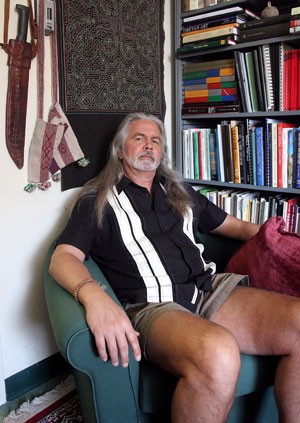

Professor Profile

Anthropology professor Mark Aldenderfer began his career in archaeology as an undergraduate student in 1970. Since then, he has excavated national and international sites, including those in Ethiopia, Guatemala and Peru.

On a dig in the late 1990s in the Peruvian Andes, Aldenderfer and his team unearthed the oldest known gold artifact to be found in the Americas.

Sociology research involving the dig – which was published in the April 1 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – indicates that early native groups living in the region valued such gold artifacts as status symbols, despite limited resources.

Aldenderfer sat down with the Daily Wildcat to discuss his ancient find.

Wildcat: When you say ‘the earliest gold artifacts,’ how early are we talking?

Aldenderfer: It’s 4,000 years old. It’s at least 600 years earlier than the previous finds of gold in the Americas. It’s not the oldest gold jewelry in the world. There’s obviously plenty of gold in the Old World that is earlier than this, but this is significant if you’re in the New World.

W: Where did you dig and when?

A: We started this project in the middle 1990s. It started with a survey for archaeological sites. We discovered this particular site called Jiskairumoko during that survey. We went back the next year with different funding and tested the site and found that it had deposits that were the right time period for the problems we were trying to research. A couple of years later, we got funding from the National Science Foundation to do large-scale excavations of the site.

W: What were you trying to find?

A: The project was designed to look at this question of how hunters and gatherers become sedentary village people – in other words, moving from mobile lifestyle to a relatively permanent lifestyle in one place. This site was one of the most important that we thought would be useful in this region to look at. The dates worked out, the deposit looked really interesting and it turned out to be the key site for much of our work.

W: How many times did you visit the Peru site until you found the necklace?

A: The full-scale excavations began in 1999. … We had been working that site since 1997, and so it was in the very first season of the large excavation that we found the necklace.

W: What was the big news with the necklace?

A: This is the earliest gold artifact in the Americas, so it was a surprise to us that it was even there. People do decorate their bodies all over the world with different sorts of beads – stone beads or bone beads or what have you – but this was the first time anyone in this region had found gold beads, No. 1. And the second thing that’s important is that these people are still hunter-gatherers; they are not quite these village people that are living in this village setting. So this signals an interesting change in social life when people begin to become sedentary. They begin to compete for different status positions. They begin to try to expand the range of their contacts from where they live to try to develop a higher standing within their own group.

W: When did you date the necklace?

A: There was a small piece of charred wood underneath the skull from which the necklace was found, and we submitted that to the UA accelerator lab. We probably dated it that year or the next year.

W: Who owned the necklace?

A: We don’t know who, but the person who was buried with it was likely to have been the owner. We are not entirely sure of what sex the person is, because the bones were in fairly bad condition. We suspect it was a woman because all the other burials of this time period are of women that we found at that site, and it’s consistent with our thinking about what’s going on at the site and what’s important about it.

W: How much do you think the necklace was worth back then?

A: You could add up how many ounces of gold it was, but it’s more of what it signifies that’s important to us. (Editor’s note: The largest of the nine golden beads weighs 5.2 grams, according to a report Aldenderfer and his team wrote about the find.) For archaeology, it’s a priceless find. For the people who owned it back in the past, this was a real mark of distinction for them. It really signaled that these are people making an effort to enhance their prestige and status by so possessing it. When you have something exotic like that, it really signals that you are trying to become important in some fashion.