September 9. Baton Rouge, Louisiana. A flash of white and yellow comes out of nowhere and drills Arizona quarterback Willie Tuitama on his team’s 20-yard line.

That flash turns out to be Louisiana State defensive end Tyson Jackson.

October 7, almost a month to the day later. Los Angeles, California. Tuitama gets drilled again. This time, he gets hit at UCLA, and this time, he hits the surface of the field with incredible force after taking a vicious hit from Bruins defensive end Bruce Davis.

And the hits just kept on coming.

November 18. Eugene, Oregon.

November 25. Tucson, Arizona.

Four cities. Four hits. One athlete. And perhaps the most misunderstood injury in the entire sporting realm: the concussion.

“”Certain things you can play through and certain things you can’t,”” said UA head athletic trainer Randy Cohen. “”Certain things are higher-risk than other things.””

A concussion is one of those things.

Most readily defined by one expert as a jolt or blow to the head that causes a change in mental status, concussions are just beginning to be understood.

“”It used to be ‘How many fingers am I holding up?'”” said that expert, Dr. Jamie Pardini, a neuropsychologist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Center for Sports Medicine. “”We’ve got a long ways to go, but we’ve also come a really long way.””

Now, the treatment of concussions is trending toward a more personalized level of management.

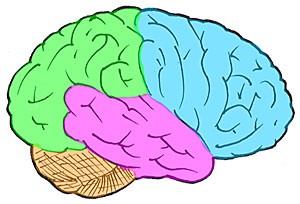

Pardini, a self-described “”graduate school nerd,”” is one of three neuropsychologists at the UPMC’s Center for Sports Medicine’s Concussion Program, a nationally renowned clinic that draws athletes from all over the United States. When it comes to concussions, whereas a neurologist has an M.D. and examines the brain to check for physical injuries such as bleeding, neuropsychologists like Pardini examine the brain’s behavior interface.

On a given day, she sees dozens of concussed athletes ranging from age 6 all the way up to the professional ranks, many of whom return in the weeks following their visit bearing signed jerseys as a thank you.

Though she’s been in the concussion field for more than three years now and works in a medical center that can see up to 100 patients a week in the busy season, Pardini said she often struggles with the stigma surrounding the seriousness of concussions.

“”If you have a concussion, you don’t have a cast, you don’t have a bandage – you look fine. The way you looked probably didn’t change at all when you had the injury,”” said Pardini, an informational packet on the newest type of neuro-imaging lying open on the table in front of her. She gestures as she talks, her hands helping to articulate her words.

“”And so here you are feeling horrible, walking around school, not feeling the same, but people are expecting you to act the same,”” she continued. “”There are all these external pressures …that I think make it difficult to win people over in terms of taking it seriously.””

Willie Tuitama didn’t take it seriously. At least not at first.

After the UCLA hit, he was asked about his symptoms. Did he have headaches? Blurred vision? Memory issues?

“”I was (telling the doctor) that I really wasn’t all that messed up,”” said Tuitama, 19.

So, with his parents on the phone, the doctor sat down with him.

“”They said, ‘Just make sure you tell him the truth, because either way, you’re not going to be playing this next week,'”” Tuitama said. “”So then I started telling the truth.””

Why’d he do it in the first place?

“”That’s just because I wanted to get back out there,”” he said.

Tuitama’s case was a widely publicized and widely debated story. After the first hit, fans and media grew increasingly concerned about whether he should sit, and if so, for how long.

The Stockton, Calif., native was cleared the week following the LSU hit and played in the next game, leading Arizona to a late-game touchdown in a win over Stephen F. Austin. And so he was fine – for a month.

With Arizona’s run game struggling and a young offensive line still searching for a way to become a cohesive unit, Tuitama faked a hand-off to running back Chris Jennings in the second quarter against UCLA Oct. 7, rolling out to his left as he looked for tight end Travis Bell.

But Bruce Davis, the Bruins’ defensive end, didn’t bite on the fake, and Tuitama’s head hit the ground with incredible force.

UA wideout Syndric Steptoe would tell him later that he was screaming so loudly, he thought Tuitama had broken his leg.

And though Davis caught Tuitama square on the chin, it was that impact with the ground that caused his second concussion within a month. Pardini said these “”temporal injuries”” to the side of the head are the most common type of impairment she sees.

Tuitama was transported to a Los Angeles hospital, where he underwent a CT scan to check for any physical abnormalities in his brain, such as bleeding. (A common misconception, Pardini said, is that concussions show up on EEGs, MRIs and CT scans: “”There’s no blood test, no brain scan or anything that we could do to say ‘Yeah, for sure, your concussion is gone.'””)

The sophomore had suffered his second concussion in a month – Cohen estimated that the number of concussions he sees on the football field in a given season can range anywhere from one or two concussions all the way up to nine or 10 – and it caused an uproar.

Some were calling for Tuitama to sit out the rest of the season. Others said he should miss the Stanford game the following week and return against Oregon State Oct. 21.

“”You’re definitely more concerned about someone who’s had back-to-back concussions,”” Pardini said, pausing before she revealed why: “”Is less biomechanical force causing increased injury?””

Translation: It might not take as big of a hit the second time.

Tuitama ended up switching to a helmet specifically designed to protect against concussions – one study published this February revealed that one of the new helmets, designed by Riddell in conjunction with laboratory research, reduced the relative risk of a concussion by 31 percent. In other words, if a vicious hit had a 20 percent chance of causing a concussion with older helmets, the new helmets reduced that chance to roughly 14 percent.

So Tuitama and his new helmet waited a month, then returned Nov. 4 at Washington State upon being cleared following Arizona’s bye week.

Though Pardini stressed she couldn’t talk about individual cases without first meeting the athlete and examining them herself, when given Tuitama’s symptoms, she said the one-month healing period “”sounds about right.””

After leading Arizona to two wins in the next two weeks, Tuitama had his team up 7-3 before taking yet another lick Nov. 18 at Oregon. He finished the series and played two more – throwing two touchdown passes – before being lifted late in the second quarter.

Though it wasn’t a concussion, he didn’t return.

Why?

This time, Tuitama told the truth. He had had a moment of blurred vision – “”It was kind of weird,”” Tuitama said, “”I was trying to get plays, and I couldn’t really see the coach (on the sideline) right …the lower half of his body was gone for some reason”” – and he knew the severity of possibly staying in the game and having another concussion. So he told the training staff about it.

Then last week against ASU, he took yet another hit. The young quarterback was sandwiched between two Sun Devil defenders well after he released a pass in the second quarter, the brunt of the contact coming from his blindside.

The hit was flagged, but Tuitama left the game. Though he tried – UA medical staff had to take away his helmet in order to stop him from attempting to re-enter the game – Tuitama wouldn’t return.

He had suffered his third concussion in less than four months.

But is he to blame for having lied in the first place and wanting to get back on the field before it’d be healthy for him to do so? Or is it what Pardini called football’s “”You need to be tough for the team”” culture that surrounds him?

“”If it was an ankle or something, I would play,”” Tuitama said before the Oregon game, “”but just being the head, it’s just so important, and if something else happened right away like that, I could have been all damaged.””

But not every athlete comes to that realization. Every so often, Pardini finds herself sitting across a table from a patient begging to be cleared.

“”It can get ugly every now and then,”” Pardini said, smiling as she folded her hands.

She took a look around the room as she thought of how she deals with concussed athletes who beg her to be cleared.

“”People take head injuries seriously at different levels,”” she said after a moment. “”Some people are still kind of in the mindset that, ‘It’s a ding, it doesn’t matter.'””

After the UCLA game, UA running back Chris Henry told a group of reporters that he gets a concussion just about every time he steps on the field and added “”the first couple of times, it’s really weird when you get a concussion if you’re not used to getting them.””

In reality, that’s probably not the case.

A 2001 study revealed that of every 1,000 athletic exposures in a game or practice of any sport, roughly six athletes sustained concussions, and Cohen said Henry’s statement was probably an instance of “”someone not understanding what a concussion is.””

Still, it serves to exemplify the type of nonchalant attitude athletes often take with concussions.

“”There is that mindset that if you’re tough enough, you should be able to shake (a concussion) off and just go back (to play) because your teams needs you,”” Pardini said.

But Cohen believes that that culture is beginning to change, and that athletes are beginning to realize the consequences of a concussion.

“”Do they underreport? Sure. And have they traditionally underreported? Sure, they have,”” Cohen said. “”But, in turn, now they’re getting more educated and they’re understanding, and they’re a little more forthright than they have been in the past.””

Maybe it’s easier to lie to a person. Or perhaps it’s tougher to lie to a computer.

Either way, it’s working.

The UPMC’s concussion center has made its biggest breakthrough with a program known as the Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Test, or more simply, ImPACT.

All Wildcat athletes must take a physical before they can see the field. Along with that physical comes the ImPACT test, developed more than a decade ago by Drs. Mark Lovell and Mickey Collins of the same UPMC Concussion Program that Pardini works for.

With one study estimating that roughly 300,000 sports concussions occur across the nation every year, it’s a program that has rapidly become widespread in use. The test is now used by the NFL’s Pittsburgh Steelers and more than 400 colleges and high schools across the country, and it’s also available online at www.impacttest.com.

Arizona adopted the software three years ago and has been using it ever since.

“”We go to every resource we can possibly get,”” said UA athletic director Jim Livengood. “”We just don’t pass (a concussion) off and say, ‘Well, that’s OK. He’ll feel better, she’ll feel better.'””

When an athlete first takes ImPACT, it provides a baseline for which to compare a concussed athlete with his or her pre-concussed self, testing verbal memory, visual memory, hand-eye coordination and reaction time.

Everything is tested both right away and after a 10-minute delay, which gives the neuropsychologists a chance to examine different types of memory with each patient.

Because the brain has to work harder after a concussion, thus making the tasks completed during the baseline test more difficult to finish as accurately and rapidly as the original test, the post-concussive test results differ from the first test athletes take.

So if a concussed athlete like Tuitama wants to return to play, his test results must return to his normal baseline levels, meaning the he’s fully recovered.

“”Any added tool you have to help in the overall assessments will help give you more concrete knowledge of what’s going on,”” Cohen said of ImPACT. “”You have a better idea of when someone’s safe and when someone’s not safe (to return).””

But while ImPACT goes a long way in helping to determine that recovery, it’s important to note that at Arizona, ImPACT isn’t the “”end-all, be-all,”” as Cohen put it, of return-to-play guidelines. Athletes face a multitude of tests in order to return to the field, the most important of which, Cohen said, is knowing the athletes themselves.

“”When you get a concussion, a lot of times, (the athlete’s) personality changes and they’re not themselves,”” Cohen said. “”And sometimes it’s a feel, so you look at them in the eyes, and you say, ‘Yes, they can answer the questions, but they’re not right.'””

Still, ImPACT gives trainers a new scientific standard with which to measure an athlete’s progress after a concussion.

“”This is the best that we know how to manage an injury given current technology and current research,”” Pardini said, “”which is a heck of a lot better than what we used to do, which is, ‘How do you feel?'””

That’s why, in years past, athletes have traditionally gotten away with underreporting their symptoms.

“”Having an objective measure, the computer test, is very important,”” Pardini said. “”Because if you want to go into a big game, you’re going to lie about your symptoms.””

Pardini continues to see a number of cases a week in which athletes try and get back on the field sooner rather than later. It’s something she’ll never stop cautioning against.

“”A brain injury is one of the – in my opinion, of course, because I’m biased – really the injury that you can’t play with,”” Pardini said. “”You can’t be 90 percent recovered from a concussion and go back to play, because then you’re in dangerous territory.””