Allan J. Hamilton is a professor of surgery at the UA. He graduated with honors from Harvard Medical School and finished his neurosurgical residency at Massachusetts General Hospital. Hamilton has worked at the UA for 18 years.

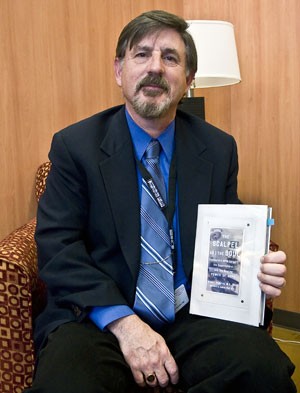

Hamilton recently published “”The Scalpel and the Soul.”” In the book, Hamilton delves into the correlation between the physical and spiritual aspects of surgery by recounting his experiences with spirituality in and out of the operating room.

Stories range from inexplicable encounters with individual patients to a story from his humanitarian trip to Africa, in which an African native waited more than 24 hours by a river because the man saw in a dream that he was supposed to help Hamilton and his crew find their way to the community the group was supposed to immunize.

Hamilton began working on the book in 2004, and it was released March 13. The book is available in the UofA Bookstore for $23.95. He sat down with the Arizona Daily Wildcat yesterday before his book signing in the UofA Bookstore to talk about the book.

Wildcat: Who is this book written for?

Hamilton: Mostly patients who are facing severe illness or major surgery. The second group is probably people in the health care profession who are taking care of these patients.

W: What were you trying to accomplish?

H: I was hoping to pass on some lessons I learned from patients about harnessing their own emotional and spiritual energies to enhance their recovery.

W: When did you decide that you needed to write this book?

H: Certainly not 30 years when I started all this. I think somewhere around 2002 I started really looking at things and thinking that of all the things that amaze me, it was more the spiritual experiences that impressed me more than the technical expertise.

W: What is one experience you talk about in your book?

H: I had a young man who had a brain tumor, a malignant cancer, and I operated on him and took care of him. His big hobby was fishing. He went through the regular regimen of chemo and radiation. He came to me one day and said, “”I know I’m going to beat this thing, but if things really get bad, I want you to promise me you’ll tell me when it’s time to go fishing.”” And it went on for several years and unfortunately the tumor grew back and he had multiple operations, but the tumor was invading his brain and his spinal cord. One day I took him aside, and I asked him if he remembered when we talked about when it was time to go fishing, and I told him it was time. And the next morning his family called me and told me he was dead. And I think I snipped that cord of hope he had. I think when he saw me give up, he gave up. It just taught me that no one has the right to take away somebody else’s hope.

W: Have you ever been under the knife?

H: Yes. The last chapter is about it.

W: In your book, you list some “”Rules to live by.”” Could you tell us some?

H: I’ll mention a couple of my favorites. One of my favorites is, “”Don’t let yourself be turned into a patient.”” A hospital has a way of removing your identity … I really think that’s a bad idea. I think you want to assert your identity. So bring your favorite T-shirt and wear your crazy sweat pants. Instead of those little paper slippers they give you, go get the big, fluffy, bunny slippers that you love. You aren’t a disease in that bed. You are a patient in the bed with a disease. Music has a lot to play, I always tell patients to make their own soundtrack for their recovery. I tell them to put together some music that will convey some of the emotions that they want.

W: What have been on some of the tracks on these recovery soundtracks?

H: I had somebody who wanted Lynyrd Skynyrd played. And the thing was, it was OK until we got to the really concentrated part of the surgery. We had to turn it down for that part of the surgery. But most of the patients have very quiet, new age, meditative music. I had one patient who wanted (the theme from) “”Rocky”” when he was emerging from the anesthesia. You know, you can just see him climbing up the stairs.

W: What would be on yours?

H: I think a lot of Bach. I think probably a couple of arias I love from Mozart. I think there might be one or two Muddy Waters in there to make sure they are backing off on the anesthesia.

W: Do you think, as a surgeon, you lose any credibility in talking about spirituality?

H: I don’t think it’s credibility that you lose. Surgeons are a very, very conservative group. We are masters of technique. We are as mechanistic a field as there is. So I think that field of colleagues asks if we should really even be talking about this. And yet you have a lot of them that come up to you and say, “”I’ve seen things I couldn’t explain and I didn’t dare tell anybody.”” I think there are a lot of people that are just afraid to discuss it. Nobody talked to me about this. You go right into this with your patients, and you don’t realize that their spiritual challenges are going to have an effect on you too.

W: Do you think medical schools will start addressing the spiritual issues of surgery?

H: They are. I think patients are really insisting on it, and I think the younger generation is responsive to it. Fifteen years ago we had less than 10 percent of medical schools even having anything related to spirituality in medicine. Now it’s nearly 70 percent.

W: And for the token school publication question: Do you watch any of the hospital shows on TV?

H: I am the neurosurgical script consultant for Grey’s Anatomy. I write all the neurosurgery that Patrick Dempsey does.

W: Is he as attractive in person as he is on screen?

H: Well, everyone knows he got the role because he looks so much like me.