Breathe easy, because the University of Arizona Health Sciences Asthma and Airway Disease Research Center and the Arizona Emergency Medicine Research Center are leading a study funded by the National Institutes of Health that is looking for a solution to the alarming amount of Emergency Room visits by children suffering from asthma attacks.

According to a 2017 study by the Center for Disease Control, 6.2 million children suffer from asthma, with the number of visits to emergency departments where asthma is the primary diagnosis topping out at 1.7 million.

Children are taken to emergency departments more often than to a primary care provider. About one third of these visits are usually are followed by a second visit within six months due to a second asthma attack. These visits are cut in half, however, by children who regularly use inhaled corticosteroids, via inhalers, after the first discharge. This is a statistic the authors of a new study by the UA Health Sciences Department are hoping to increase.

RELATED: UA researchers develop snakebite venom inhibitor

According to a UA Health Sciences press release, the study will include children ages six to twelve who are in kindergarten to fifth grade. Each will be provided the proper inhaler medication for in-home usage and additional medication for the child’s school’s health office.

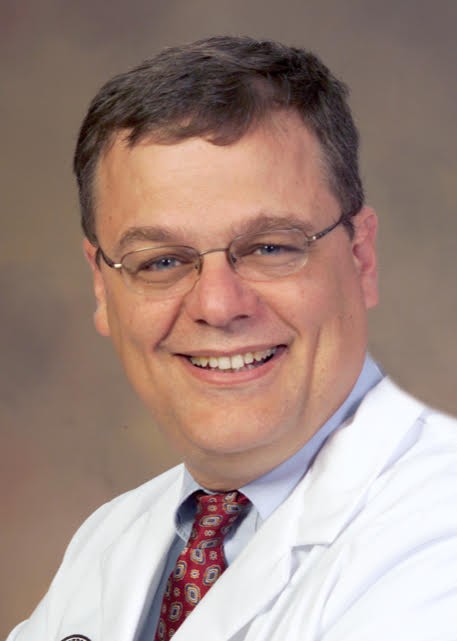

“We are looking to see if we can engage the school environment as a part of the medical home,” said Dr. Kurt Denninghoff, the associate director of the AEMRC. “Often in the emergency department, we see underprivileged kids who have [an] asthma attack aren’t getting help they need. We have proposed using school and the school nurse as way to deliver asthma-control meds to kids with high risk, with the hope being a decreased number of attacks and visits these kids experience.”

The school’s health office will receive an “asthma action plan,” as well as supervised use of once-daily medication each school day, according to the press release. Parents will receive general asthma-management education on the use of the medication and potential side effects.

Parents of the children will also be advised to supervise at-home use of the inhaler on weekends, holidays and absences from school.

“We know that if the kids use inhaler meds appropriately, it helps prevent attacks and reduce severity,” Denninghoff said. “The question isn’t ‘Does the medicine work?’ It is ‘Does using this approach to delivering the medication work?’ It is about how best to help at-risk children miss less school days and have less hospital admission.”

Since the study is on children on Medicaid, Denninghoff said he does not see cost as one of the main reasons the problem is occurring.

“The issue is … [when] we tell them they need to use the inhaler, they choose not to,” Denninghoff said. “Cost could be an issue for people without insurance, but it comes down more to convenience or neglect. We would like to reach children in an environment where those things aren’t happening, to get a better sense of things.”

RELATED: ‘Marriage’ of ideas: Husband and wife team-up to combat opioid epidemic

Participants in the study are advised to complete a follow-up visit with their child’s primary asthma care provider within seven days of discharge from the emergency department, according to the press release.

The asthma care physician will also receive a letter with information regarding the child’s participation and specific medication.

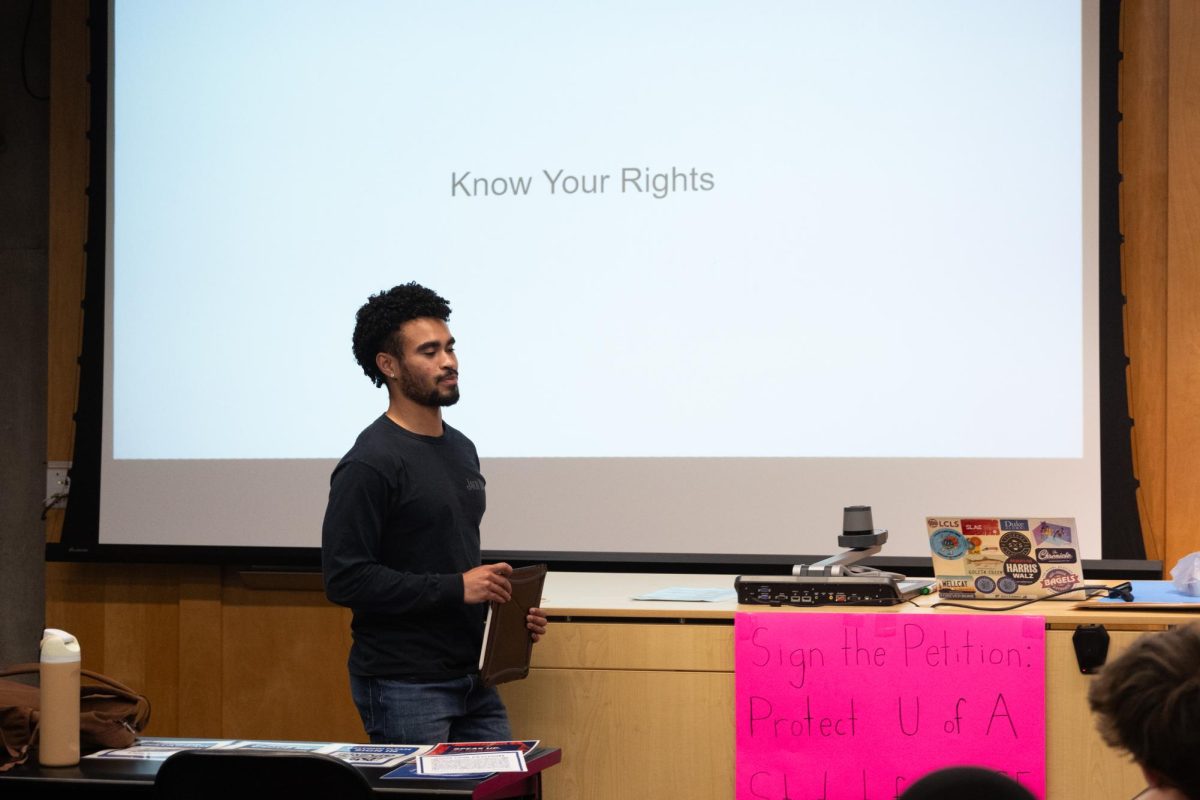

A web-based training program will be made available to school nurses and health staff to make sure they are properly trained to handle the medication, with a toll-free hotline operated by experienced personnel available to anyone with questions, according to the press release.

Follow Mark Lawson on Twitter