UA researcher Yann Klimentidis received a $115,000 grant for research into lipedema, a condition that causes disproportionate amounts of fat to develop around the hips, legs and thighs.

The condition is found almost exclusively in women, and is easily mistaken for standard obesity. It cannot be treated with simple exercise and it causes those affected to be overly sensitive in the afflicted areas, Klimentidis said, causing pain on even the slightest touch.

Klimentidis is focusing on finding genetic patterns and indicators to help learn more about the condition and potentially find a treatment. His funding is coming from the Lipedema Foundation, which is only just beginning to fund research.

“Lipedema is rarely diagnosed and poorly understood,” Klimentidis said.

The main effect of lipedema is persistent fat developing around the legs and thighs, with less developing around the belly. This pattern means that women with lipedema show lower risk for developing diabetes or heart problems, according to Klimentidis.

“The difference is it’s a specific type of fat patterning, whereas obesity is a general crude description of having a lot of weight,” Klimentidis said.

The fat itself developed in lipedema is also different, said UA college of medicine associate professor Karen Herbst.

“Normally fat is smooth, with a rubbery feel on the thighs, but in lipedema it feels like little pearls,” said Herbst. “When we train people to identify lipedema, we tell them to search for those nodules.”

RELATED: Soy may help prevent breast cancer

Studies have also shown that lipedema fat is persistent, and even removal by liposuction is not perfect. Surgeons in Germany have done long term studies on liposuction on lipidemic patients, and for about five percent of patients, it is ineffective, Herbst said.

“For the remainder of women, debulking lipedema fat is effective at improving quality of life, but after an extended period, it would likely eventually come back,” Herbst said.

Currently, liposuction is the only treatment for lipedema.

The theory for why lipedema is found primarily in women is that women are already genetically programmed to put fat in those areas, so lipedema is almost like an overproduction of that programming.

“You could argue that it is an extreme of typical female fat patterning,” Klimentidis said.

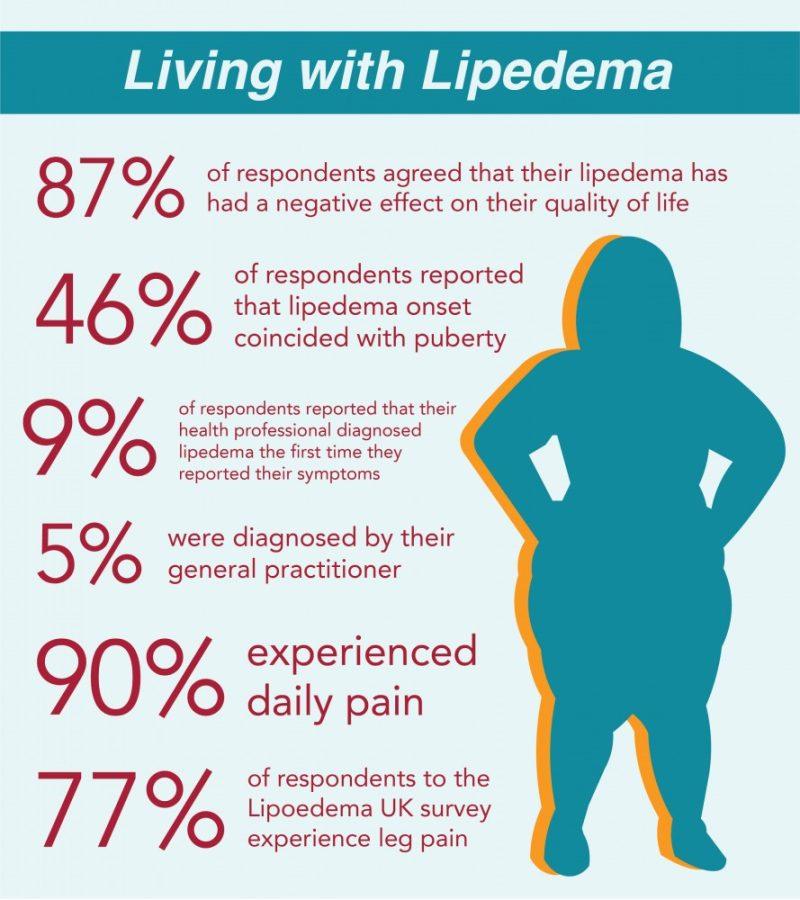

Evidence also shows that lipedema develops around puberty, a time when different hormones rise in men and women, according to Herbst.

“Since hormone levels rise in men but they don’t develop lipedema, we think it may have to do with the difference in hormones, specifically estrogen,” Herbst said.

Herbst, who has also received a grant for lipedema research, is focused more on observing skin and fat tissue under a microscope. The goal of her research is finding differences in the tissue and blood flow between those with and without lipedema.

“What we have found is women with lipedema tend to have larger bundles of blood vessels and more inflammatory cells,” Herbst said, “We’ve also done ultrasounds, and have found lipidemic patients are more prone to leaky vessels and fibrosis.”

Lipedema has three stages, with each stage being more drastic than the last, according to Herbst.

“There’s something different about the structure of tissue found in women at stage three, which has big lobes of fat that hang and impede blood flow,” Herbst said.

This all leads to interference in proper blood flow, symptoms Herbst believes further perpetuate fat development.

RELATED: Many ways to use a mushroom

Klimentidis’ research focuses on identifying genetic patterns in women with lipedema. He has been given access to the UK Biobank, a cache of genetic, disease and physical data.

“I’m sorting through the data to find women with physical attributes like lipedema,” Klimentidis said. “There’s data about fat deposits around the leg, arms, trunk, waist and hip circumference, and leg pain.”

While the data does not specify who has lipedema, Klimentidis can identify the symptoms and sort through those who suffer from it. By observing the genomes of lipidemic women, Klimentidis can find potential patterns and indicators.

“By identifying genetic risk factors, we get insight into the biology of the disease, issues with genes and potentially identify if someone is at risk,” Klimentidis said.

Lipedema is still something the medical field knows very little about, so Klimentidis said he can’t narrow down his search and will have to analyze entire genomes.

He must also search whole genomes because, in many cases, he said, more than one gene is responsible for your physical and biological characteristics.

“It’s really probably hundreds or thousands of genes that in combination put you at risk for the disease.” Klimentidis said. “For example, there is no single tall or short gene, it’s many genes that determine height.”

Follow William Rockwell on Twitter