Oftentimes, change can be good. Other times, change can be another hurdle to getting back to the sense of “normalcy” we felt before the pandemic.

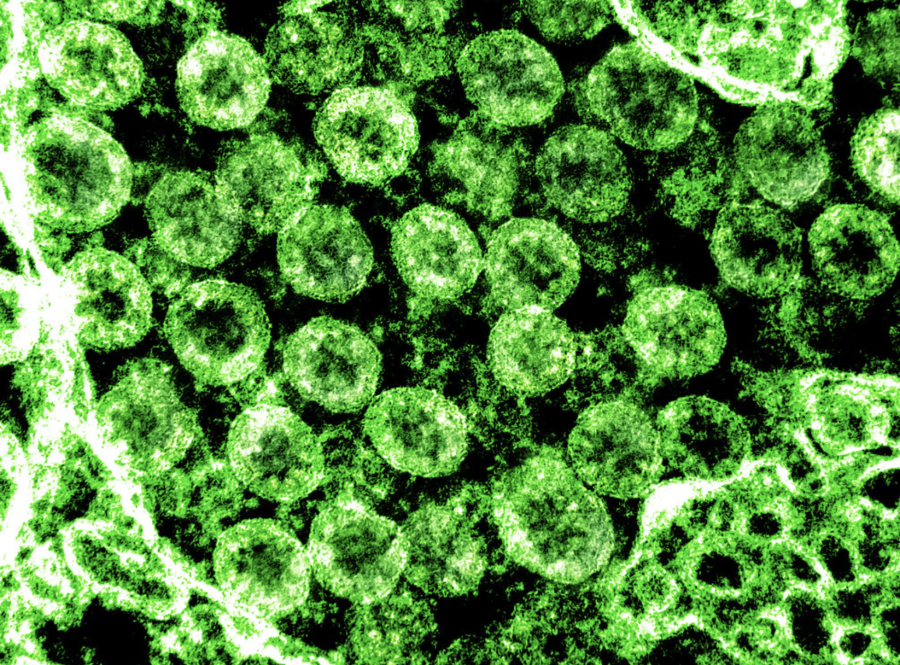

By its very nature of being an RNA virus, the novel coronavirus is susceptible to changes in its genetic code. In the past year, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has mutated a number of times, giving rise to new variants.

The three major variants present today are the United Kingdom variant (B.1.1.7), the South African variant (B.1.351) and the Brazil variant (P.1). The presence of these variants, which are oftentimes more contagious or fatal, reinforces the dire need for mass vaccination, which proactively impedes the spawning of new variants.

Experts currently estimate that around 70% of the population will need to be vaccinated in order to reach herd immunity, “the indirect protection from infection conferred to susceptible individuals when a sufficiently large proportion of immune individuals exist in a population.”

U.K. variant (B.1.1.7)

The U.K. variant, as the name implies, was first identified across the pond in the United Kingdom. This coronavirus variant, based on current research, has higher transmissibility than the wild-type, or original, strain. On the bright side, the current vaccines all work pretty much just as effectively on this strain.

This variant appears to be more infectious due to several mutations in its spike protein, which the coronavirus uses to attach to cells.

As of Thursday, March 25, there have been 8337 reported cases of infection by the U.K. variant in the United States across 51 jurisdictions, per the Centers per Disease Control and Prevention. In the middle of January, the CDC estimated that the B.1.1.7 variant would be the dominant strain in circulation by the month of March.

The U.K. variant was first identified on the University of Arizona’s campus on March 25, per an email sent by Dr. Michael Dake, the Senior Vice President of UA Health Sciences.

RELATED: New coronavirus strain B.1.1.7 to be dominant by March, CDC says

South African variant (B.1.351)

The South African variant was first identified in South Africa and was first identified in Arizona late on Friday, March 26. This coronavirus variant has not been researched as extensively as the U.K. variant, but based on current research, the current vaccinations still work on this strain, just not as effectively as on the wild-type.

As of Thursday, March 25, there have been 266 reported cases of infection by the South African variant in the United States across 29 jurisdictions, per the CDC.

“According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, this SARS-CoV-2 variant, which spreads at a faster rate, was first detected in the U.S. at the end of January. The CDC has advised that currently authorized vaccines so far appear effective against this variant,” according to a statement released by the Arizona Department of Health Services on March 26.

RELATED: Arizona opens vaccine eligibility to residents 16 years of age and older

Brazil variant (P.1)

The Brazil variant was actually first identified in Japan, in people who had recently traveled to Brazil, and to date, is the least widespread of the three strains in the U.S. Based on the current research, the P.1 strain is able to evade our current vaccinations to some extent, but not very well. P.1 is a close relative of the South African variant and it has some of the same mutations on the spike protein.

As of Thursday, March 25, there have been 79 reported cases of infection by the Brazil variant in the United States across 19 jurisdictions, per the CDC.

Follow Amit Syal on Twitter