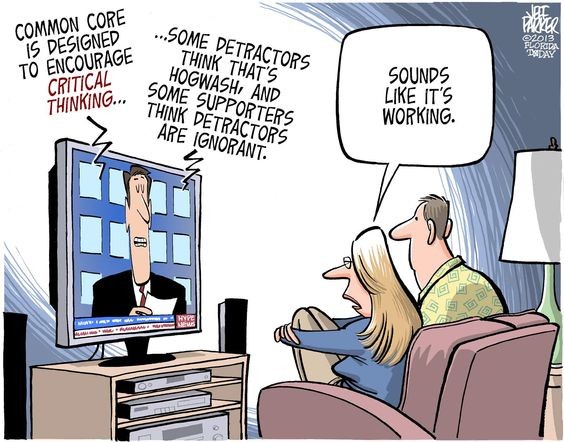

When students make the choice to attend college, they choose to further advance their knowledge and cultivate critical thinking skills. Many students, however, do not see such improvement until senior year or, at worst, ever.

What exactly is critical thinking? The Critical Thinking Community defines it as a “mode of thinking—about any subject, content or problem—in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully analyzing, assessing and reconstructing it. … It entails effective communication and problem-solving abilities, as well as a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism.”

“[Forty five] percent of students made no significant improvement in their critical thinking, reasoning or writing skills during the first two years of college. After four years, 36 percent showed no significant gains in these so-called higher-order thinking skills,” according to a study using data from the Collegiate Learning Assessment.

The study also goes on to say students devoted less than one-fifth of their time—including hours spent studying and in class—each week to “academic pursuits.” Students also spent 51 percent of their time—or around 85 hours each week—socializing or being involved in extracurricular activities, according to the study.

As a student studying linguistics and anthropology, my fields have cultivated my critical thinking and creativity in a variety of different ways. Linguistics taught me to find patterns within human language and to articulate these findings through writing. Anthropology taught me how to understand diverse cultures and societies through a variety of lenses and to cogently illustrate my knowledge verbally and through writing.

Both of these fields are research-intensive and require analytical writing and reading skills in conjunction with reasoning skills. This is also the case with many of the fields in liberal arts, the social sciences, humanities, natural sciences and mathematics.

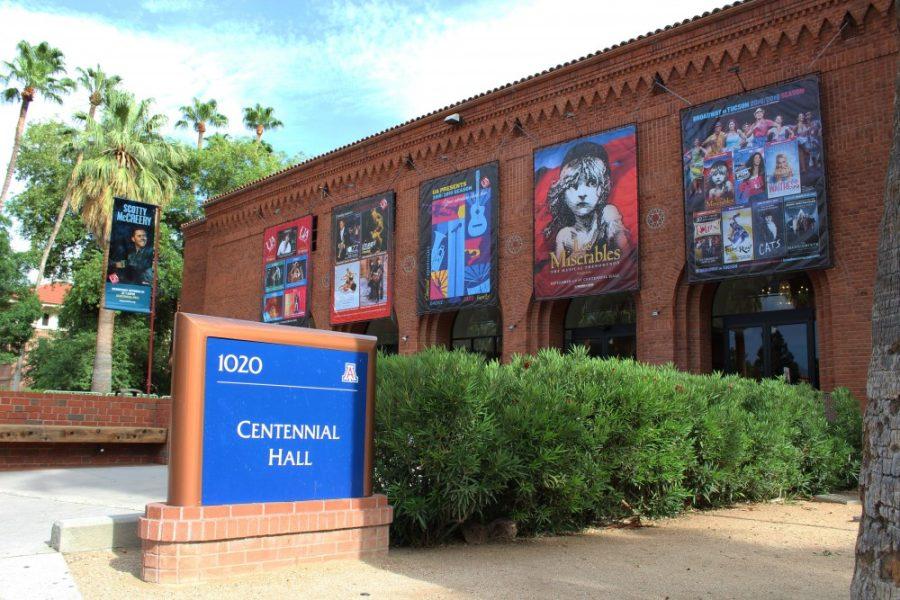

Although many general education courses at the UA may not have an instantaneous impact on our long-standing knowledge, after a while, we may realize they did teach us something.

These courses, which lowerclassmen often assume are useless and a waste of time, offer an alternate perspective through which to understand the world. They aid in developing and refining critical thinking skills by illuminating the path to applying knowledge and capacity to form valuable connections to a variety of disciplines.

These erudite experiences are occasionally hindered in the classroom. Many classes are too large to promote critical thinking, leaving many first and second-year students short of their full potentials.

In some instances, a professor or instructor will pose a question to students only to hastily move on without giving students the time necessary to form an opinion and provide a well-reasoned response.

I recall a time when I was in a course and a student raised her hand to ask the professor if it was OK to disagree with him in her essay. The professor was shocked she asked such a question, he ultimately allowing her to disagree with him as long as she supported her position.

Critical thinking and creativity should be encouraged in the classroom. If an instructor or professor degrades such development, what is the point of being in that restrictive environment at all?

For critical thinking and creativity to occur in classrooms, students must inspire and push students to reach their potentials through circumnavigating the pervasive group-think mentality. Professors must allow classes the chance to form original, analytical insights on various topics. Students must also work to inadvertently devalue their skills and potentials in favor of those who have already attained expertise in the topic at hand.

Follow Michael Cortez on Twitter.