The last time I saw a movie that confined itself predominantly to a car, it was fall 2013, and the film was the action-thriller “Getaway” starring Ethan Hawke and Selena Gomez. That movie was an abomination — but “Locke” is not. It is a highly engaging, enthralling, character-driven piece.

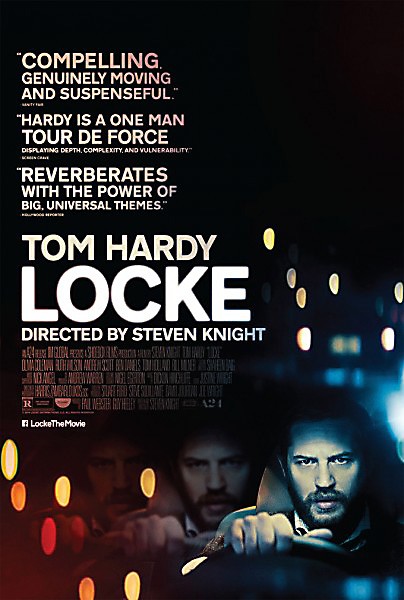

The Loft Cinema is one of 50 independent theaters across the country that participates in the New York Film Critics Series. Roughly once every month, a preview screening of a film is shown, on the same night, to audiences across the country. After the screening, oft-quoted “Rolling Stone Magazine” film critic Peter Travers moderates a Q&A with some of the more prominent people who were involved in the film, providing insight and commentary on what the audience has just immediately seen. In the case of “Locke,” Travers spoke with director Steven Knight and star Tom Hardy.

The concept of “Locke” is a simple one: Ivan Locke (Tom Hardy) is driving south, away from his home, on a motorway in London in the middle of the night. With the exception of the first 30 seconds or so, the entirety of the film’s 85-minute running time Locke is in his car. As he drives, confined to the driver’s seat, his picturesque life devolves via a series of phone calls.

Films like “Phonebooth,” “Buried,” “Getaway” and “Locke” fall under the grim-sounding subgenre of “claustrocore.” I don’t know how often the phrase “claustrocore” comes up in serious discussions about film, but it sure is fun to say. It sounds like the goth, black eye-liner-wearing older brother of “mumblecore.” The conceit of this subgenre, deriving its name from “claustrophobia,” consists of films that generally have one protagonist who is confined to a single space. Not only must the character, space, script and narrative be interesting, but the actor must carry the whole film on their shoulders.

Knight would be hard-pressed to find an actor who could play the role as well as Hardy. Hardy has shown that he is more than willing to take roles that eschew the normal. As Bane in “The Dark Knight Rises,” he wore a mask that covered half of his face, relegating him to an almost purely physical performance and forcing him to do all of his dialogue after shooting. Hardy is the only person who appears on screen throughout “Locke,” with the other facets of his life calling in through the phone.

Locke is driving to a woman he had a one-night stand with, who is in the hospital, about to give birth to his child. He not only fields her calls, but he also has to break his infidelity to his wife over the phone.

Locke is a construction foreman and, of course, the next morning, he is supposed to oversee one of the largest concrete pours in the history of England. He must coordinate the plans for the pour with his right-hand man back at the construction site.

Sometimes there is silence, and sometimes there is a flurry of calls, but Locke addresses them all calmly and collectively.

Hardy’s adopted Welsh accent, which he said he employed to encapsulate both the sensitivity and gruffness of the region of England that Locke is from, is the smooth, reassuring through line in the mounting chaos. Knight, primarily known as a screenwriter, has penned a script that is both dramatic and funny. The screenplay deftly executes the tall task of carrying a film that is all dialogue.

There are some minor bumps in the road here and there. Locke has imagined conversations in the car with his dead, neglectful father, and the ending arrives suddenly. Perhaps, though, that’s because the film was the fastest hour and a half I’ve sat through at the theater this year. “Locke” is enthralling, daring cinema and, with Hardy’s performance, is largely rewarded for the risks it takes.

Grade: A-

@FilmandEDM