Rebecca Reed, a UA researcher and family studies and human development doctoral candidate, is studying how close relationship partners help each other recover emotionally and immunologically after psychological stressors such as arguing. Reed has recently completed collecting all of the data for the Couples’ Healthy Immune and Emotions Study and is currently processing the data.

“I’m interested in how these daily stressors with partners influence their daily immune functioning, with the idea that it is these daily processes that compound over time and put people on certain trajectories towards various health issues,” Reed said. “How we interact with our close relationship partner, how does that facilitate faster immune recovery?”

Immune systems respond to physical stressors, but they also respond to psychological stressors when we experience negative emotions. The immune system responds the same way to both stressors. Evolutionarily, stress was a reliable enough signal of impending danger. It meant someone was about to be physically attacked or wounded, and the appropriate immune response would be mounted, Reed explained.

“Nowadays, we’re not being attacked,” Reed said. “We’re just experiencing these daily stressors and hassles, so it’s important for that response to recover appropriately when it’s no longer needed.”

Recovering effectively is just as important as reacting effectively, Reed said.

“Science has shown that it takes time for the immune system to recover after it becomes activated by stress, such as an argument with your partner,” said Mary-Frances O’Connor, an assistant professor of psychology. “But what is not yet understood is how long it takes to recover and whether that is a different length of time for different people.”

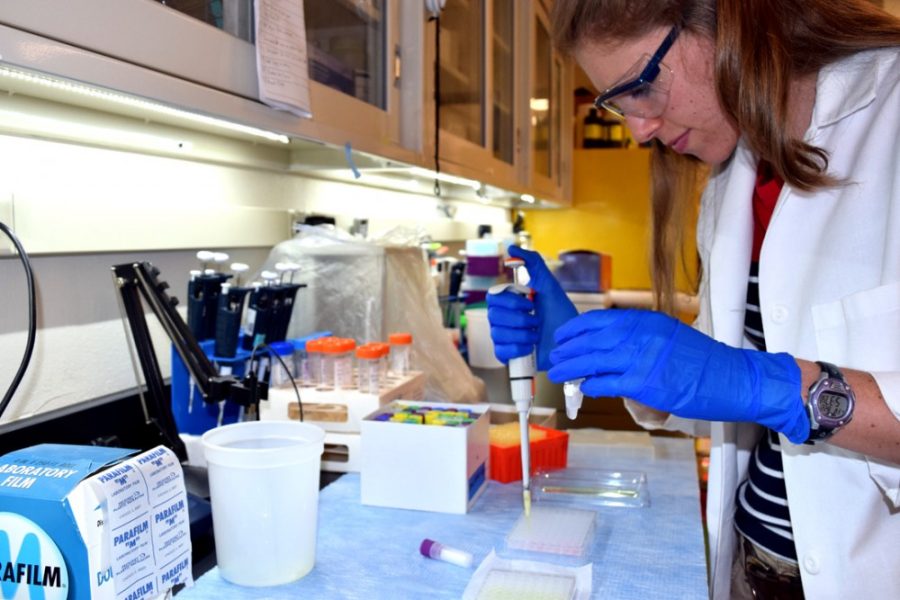

Reed is studying the immune response to psychological stressors by looking at the immune indicator interleukin 6 in saliva. IL6 indicates an immune response. This is one of the first studies to use the salivary method to look at changes in immune functioning over multiple days, Reed said.

To conduct the study, Reed obtained baseline samples of her participants’ IL6 levels to see their natural rhythm and then introduced the psychological stressor. The stressor she used was having couples talk about an area of disagreement in their relationship. She then measured IL6 levels for two days afterwards to see how long it took for their immune systems to recover.

Reed also recorded their interactions on the day she introduced the stressor to see how partners helped each other co-regulate their emotions to see if it related to immune recovery.

“Co-regulation is happening when you see both people emotional, but then come into sync with each other,” said Emily Butler, an associate professor of family studies and human development and Reed’s primary advisor.

The effect of co-regulation is for both people to calm down after a negative emotion and ultimately get to a happier place, Butler said.

“I think what we might see is that couples who didn’t effectively regulate their emotions will have a higher [IL6] rhythm than their normal rhythm for the rest of the day or even into the next day,” Reed said.

This study is a step in the right direction to see how certain interactions with a close relationship partner facilitate better recovery and, ultimately, better health, Reed said.

“What we do in our relationships affects our health,” Reed said. “It’s something to become more aware of in our everyday life.”

Follow Julie Huynh @DailyWildcat