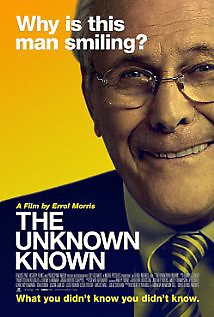

The number of times Donald Rumsfeld impulsively smiles in the new documentary “The Unknown Known” will surely astound you, especially since about 90 percent of the film is a discussion on terrorism, torture and the casualties of war.

It’s this type of evasive persona that filmmaker Errol Morris objectively explores while interviewing the former Secretary of Defense like he’s under interrogation for his job performance during the George W. Bush administration.

The 90-minute interview is narrated and sequenced by Rumsfeld reading aloud sections of the more than 1,000 memos he drafted during his time at the Department of Defense. It’s a clever strategy by Morris to force Rumsfeld out of his comfort zone and confront his involvement with America’s invasion of Iraq.

Rumsfeld jumbles his words as he struggles to answer Morris’ questions eloquently, and he soon finds himself in a sinking ship of language, text and double meanings.

Viewers looking for Rumsfeld to admit his complicity will be disappointed by the subject’s suave ability to avoid answering any of Morris’ questions directly. The film quickly becomes less about prosecuting Rumsfeld and more about parading his cartoonish exterior.

It seems like Morris takes delight in showcasing the contradictions Rumsfeld makes in his statements. One sequence has Morris asking Rumsfeld about the confusion Americans had with the link between Osama Bin Laden and Saddam Hussein. Rumsfeld nervously dances around the question, and then Morris cuts to a press conference in 2002 in which Rumsfeld boldly confirms the correlation between Iraq and Afghanistan.

It’s embarrassing errors like this that make this documentary an open buffet for the more liberal-minded. Morris makes no political apologies in identifying the fallacies of the Bush administration, which he does convincingly by highlighting Rumsfeld’s tactic of hiding behind paradoxical semantics.

The title of the film itself alludes to a philosophy dictated by Rumsfeld that explains the complexity of national security. According to Rumsfeld, there are four categories of intelligence; the “unknown knowns” are the facts one thinks are known but actually aren’t.

Rumsfeld’s rhetoric disappears into a cyclical abyss along with all the other promises, secrets and talking points of this finely tuned politician. Morris covers Rumsfeld’s history all the way back to his days as a congressman in the early ’60s, and up through when he was a final candidate to be Ronald Reagan’s vice president in 1981.

In between these two points is a peculiar side story of Rumsfeld’s plausible involvement with the Watergate scandal; Richard Nixon admitted to distrusting the then-Counsellor to the President.

Morris’ style of documentary filmmaking is a mash-up of archive footage, abstract metaphors and elaborate re-dramatizations. His narrative attempts to revitalize history through the Aristotelian model of the flawed protagonist.

Rumsfeld is dramatized as a victim of hubris, and he only scratches the surface of his journey to salvation when he discusses his decision to resign as Secretary of Defense in 2006.

Morris should be given credit for humanizing a political figure who seems to instinctively hide behind a façade of manic ambivalence. By the end of the film, the only thing Morris wants us to know for sure about Rumsfeld is that the man himself really does not know anything.

Republicans are advised to stay away from this feature, as it will definitely make them reconsider their votes for Bush in 2000 and 2004. Those looking to better understand the faulty individuals behind big government decisions are encouraged to see a screening of “The Unknown Known” at The Loft Cinema, where it will be playing through Thursday.

@KevinReaganUA