Ear worms are those little melody snippets that pop up and replay in your head at the most random of times and simply refuse to leave. Everyone’s had them at least once in their life, and some find themselves listening to multiple ear worms a day. But why do they occur, and what does their existence say about the relationship humans share with music? The Arizona Ear Worm Project works to answer these questions.

The Arizona Ear Worm Project is the brainchild of master ethnomusicologist Dan Kruse.

“I had an inherent interest in what music means to people,” Kruse said.

After hearing about a British woman doing research on the subject of ear worms, Kruse began to wonder just how songs getting stuck in people’s heads plays into the relationship between humans and music.

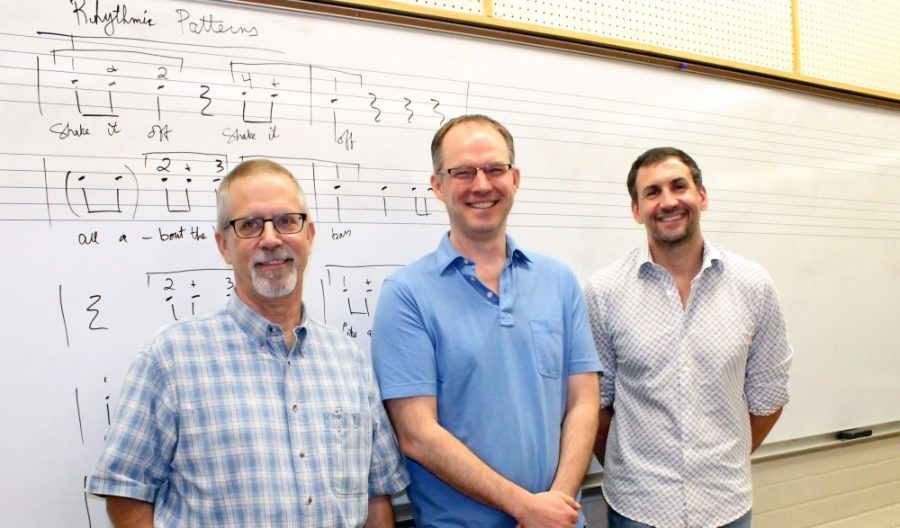

In order to conduct his research, Kruse decided to submit a grant to the UA Confluencenter for Creative Inquiry, an organization dedicated to funding interdisciplinary projects involving the arts, humanities and social sciences. Kruse wanted to take a novel approach to his ear worm research and recruit people to work with him who came from different backgrounds and brought varying perspectives to the table. He teamed up with Donald Traut, associate professor of music theory at the Fred Fox School of Music, and Andrew Lotto, associate professor of speech, language and hearing sciences, and the three began their research.

The team first put together an online survey that asked about people’s ear worm experiences and music history. From there, they invited certain participants to take part in a computer test of their musical perception abilities and to be interviewed by Kruse.

The test results answered the one question that everyone has about ear worms: just what makes a song become one? It seems like there should be some unifying factor between these tunes, whether it be similar melodies, common beats or certain musical patterns. The Ear Worm Project team wanted to address this question, among others, and ended up with some interesting results.

After analyzing the data from the survey, perception test and fixed interviews, the team compiled an ear worm song database of every infectious tune mentioned by the study’s participants. Out of the hundreds of reported ear worm melodies, very few of them ended up being repeated.

“One of the most interesting things was how varied and different the songs were that people were choosing,” Lotto said. “Initially it was, ‘What’s common amongst everybody’s ear worms,’ and now we’re starting to ask the question, ‘What’s common about one person’s ear worms?’ ”

The trio shared this conclusion among other research project findings Oct. 7 at Playground Bar and Lounge’s Show and Tell @ Playground: “Can’t Get You Out of My Head!” The talk featured several clips from “TRACKS,” Kruse’s short documentary on the Arizona Ear Worm Project.

The ear worm team is very passionate about the subject of their research and is looking forward to sharing their intrigue with their audience. Each of the three researchers said they enjoyed the collaborative process that took place between people they might have never encountered on a daily basis.

“This project allowed me to interact with other really smart people while still giving me the chance to share my knowledge with them,” Traut said.

At the talk, each researcher presented ear worms from their individual perspective: Lotto focused on music cognition and perception, Traut on music theory, and Kruse on what he dubbed the “reported ear worm experience.”

“Music’s power over people is really quite amazing,” Kruse said. “You don’t run into people walking down the street who say, ‘You know, I’ve got a Picasso painting stuck in my head.’ Music does this to us in a way that other things don’t.”

Follow Victoria Pereira on Twitter.