Imagine a time where MTV and reality television doesn’t rule the planet. Radio doesn’t exist, nor does the ancient art of silent movies. Electricity is just being discovered and the United States continues to grow with the insurgence of immigrants from all over the world. It is in this era that a new phenomenon sweeps though the United States – vaudeville.

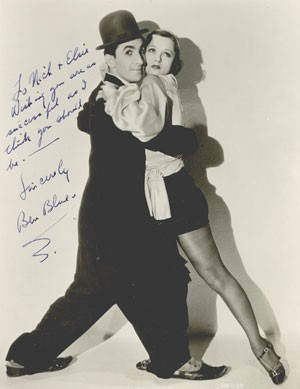

Consisting of short variety acts, vaudeville provided Americans with a cheap, fun form of entertainment – a moment to sit back and relax or a chance to get in their 15 minutes of fame. It introduced the population to performers like Charlie Chaplin, Fred Astaire and Will Rogers. People flocked to local playhouses, saloons and theaters see the shows. It disappeared as quickly as it began with the advent of technology, however, leaving many of its less famous, yet talented performers long forgotten.

Years later, these forgotten singers, dancers, actors, unicyclists and fire breathers have found a new home and a new chance at fame at the UA.

On Tuesday, the UA received an expansive collection of Vaudeville memorabilia from the American Vaudeville Museum. The museum, located in Boston, closed after director and founder Frank Cullen decided to retire to the southwest. Since his retirement, Cullen has searched for a university that is worthy of the collection.

After hearing that Cullen was looking for a place to house the collection, David Soren, a classics professor and former vaudeville performer, pursued the possibility of bringing it to the UA.

“”(I) was a consultant with the museum and knew they were going to retire,”” Soren said. “”He and his partner are now in their ’70s.””

Determined to bring the collection to Tucson, Soren traveled to meet with Cullen, and worked for three years on a grant to aid in the fight.

“”It’s one of the largest collections in the world,”” Soren said. “”This is an incredible collection and something we should have.””

After three years and a wide search across the country, Cullen decided on the UA. He thinks that the special collections department housed in the library will be able to give ample care for the collection, which includes countless numbers of old programs, costumes and video and audio recordings.

The UA Main Library is “”among the most innovative and useful in the United States,”” said Cullen at the first presentation of the collection, held on Tuesday.

The School of Theatre Arts also worked closely with Soren to convince the museum’s director that the UA was the right place for the collection. “”My main role was to meet with Frank Cullen and talk to him about the theater training program and arrange for him to meet with our acting students,”” said Jerry Dickey, vice director for the school.

The UA hosts a strong musical theater program and there is a lot of cross over with vaudeville, Dickey said.

“”(Cullen) wanted it to be at an institution where some of the performing art students were still putting vaudeville in to practice,”” he said. “”He saw this as a place where students are hoping to go in to the profession.””

The idea of vaudeville dates back to the end of the medieval era, Dickey said. It became a phenomenon in the U.S. near the end of the 19th century.

“”Vaudeville was really the main entertainment venue for mass audiences,”” he said. “”America was coming of age with waves of immigration and urban cities expanding – vaudeville expanding with it.””

Vaudeville originated in “”variety”” shows, which catered mainly to men and also featured prostitutes and gambling. “”Good government”” reformers, Cullen said at the presentation, thought these places were “”dens of vice and corruption,”” and tried to push them out of towns.

In response, variety club owners decided to clean up their act and try to attract women and children to their shows too. They rid the shows of prostitutes and gambling and renamed the shows “”vaudeville,”” he said.

“”Vaudeville has no unifying plot,”” Cullen said. “”The components of vaudeville don’t even share a common style. You don’t know from one act to another what you’re going to get.

“”Unless, of course,”” he added, “”you have a program.””

Today the composition of vaudeville acts can be compared to hit television shows like “”American Idol,”” “”So You Think You Can Dance”” and “”America’s Got Talent,”” said Dickey.

“”Anyone could audition or try out,”” he said. “”It was up to the performer and audience to decide if the act was a hit or not.””

The show usually consisted of twelve acts, ranging from singers and dancers to unicyclists and fire breathers, said Soren.

They started in saloons and bars but as the century progressed, it expanded into formalized venues. Managers set up touring circuits and acts were contracted to perform for a certain amount of time. By the 1930s, there were over 4,000 vaudeville theaters in the U.S.

But with the advent of radio and motion pictures, Vaudeville started to become a dying art, said Dickey.

“”(Motion pictures) were partly what killed it off. Once a vaudeville performer put it on film, the novelty of their live act wasn’t there anymore,”” Dickey said. “”It became easier for the performers to make quite a bit of money from doing (movies) and they didn’t have to tour from city to city. “”

Because many of the vaudeville acts were performed live and not recorded, they were lost and forgotten about. Having Cullen’s collection is like discovering a lost era, said Soren.

“”We have rock music, we have hip-hop, we have rap. You can go to iTunes and we can find these things. 1880 to 1930 – what was popular music? People don’t know.

“”Everything that was going on in America is there,”” he added. “”It’s not just about entertainment … we can see the history of the United States, we see popular opinion.””

Soren believes that the collection will give credit to the many forgotten names that paved the way for entertainers today.

“”There are many, many important names – like Bert Williams,”” he said. “”He was the first black man to perform in front of a white audience. Black rappers owe everything to this man, but they have no idea who the hell he is.””

The collection will also benefit many students involved in the performing arts, Dickey said.

“”These are types of entertainments that have been under-chronicled by historians,”” he said. “”Getting students to encounter primary documents – bills, scripts, acts, monologues or visual recordings or sound recordings and costumes – it brings history alive in a way that it doesn’t in the textbooks.””

– Justyn Dillingham contributed to reporting.