In the past month, there has been a resurgence in the consumption of plague stories and apocalyptic fiction. Pandemic films like “Contagion” and Netflix’s “Outbreak” have risen to particular prominence according to Business Insider, as well as Emily St. John Mandel’s novel “Station Eleven.”

Being older works, the revival of these stories during the time of COVID-19 begs the question of why people turn to such stories now. What can these stories teach us?

“[Science fiction] has had an obsession with catastrophes … I think our personal and cultural fears of mortality have driven everything from The Epic of Gilgamesh to The Andromeda Strain,” Christopher Cokinos, an associate professor of English and affiliated faculty member of the Institute of the Environment at the University of Arizona, wrote in an email.

RELATED: Face-to-Face: The duty of the mid-pandemic professor

UA Associate Professor of English Scott Selisker teaches a science fiction course every few semesters, and his interest in the subject has appeared in his research and writing.

He attributed this phenomenon to our desire to properly digest and understand recent events.

“One thing fiction is really good at is processing the intellectual, cultural and political consequences of abrupt changes in our lives,” Selisker said in a Zoom interview.

The plague narrative is not novel. The zombie apocalypse trope is a well-known take on an extreme, fictional pathology. One of the earliest plague stories was Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, a story about not only the stain of Oedipus’ famous family, but of the mystery of a plague that led him to his fate.

The plague investigated by Oedipus was likely, according to the Centers for Disease Control, the Plague of Thebes, recorded by the Greek historian Thucydides around the same time. These sorts of coincidences — real epidemics coinciding with the creation of plague fiction — continue into modernity.

Selisker explained that plague fiction is often inspired by real outbreaks. For instance, “Contagion” and Ling Ma’s “Severance” were both inspired by SARS and H1N1, along with a slew of other stories.

RELATED: UA Financial Sustainability Emergency Response Taskforce implemented in response to COVID-19

The fiction is far more extreme, exacerbated even, but that may be the point.

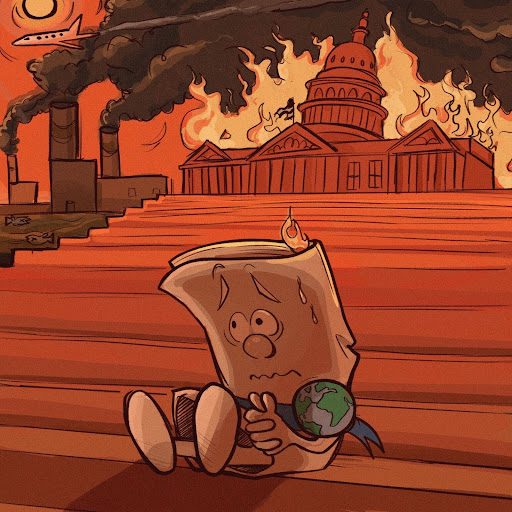

Cokinos explained that science fiction about pandemics is interested in “clearing the stage” of society to “set up new relationships, new systems, to test ourselves in a thought experiment about extremity.”

“Though science fiction has largely preferred the telescope to the microscope, that is outer space to invisible space, the genre helps us understand the vast scales from the very small to the very large–all sort of unfathomable in every day terms–in which we operate,” Cokinos said in an email.

In terms of science fiction, Selisker described the plague as “the thing that wipes out everything on Earth and then allows us to think about the difference between the ‘Before’ and the ‘After.’”

There is always the world before the virus begins its damage, and the world after is eternally changed. According to Selikser, distinguishing between the two worlds in real life is what plague fiction allows people to do.

Apocalyptic fiction in general often follows a rather succinct formula. What “War of the Worlds,” “Contagion” and “the Walking Dead” have in common is the story structure. “War of the Worlds” was written in 1898, but H.G. Wells still managed to illustrate how fear and materialism are linked in a way that is recognizable even to modern readers.

“The man was running away with the rest, and selling his papers for a shilling each as he ran—a grotesque mingling of profit and panic,” Wells wrote in the novel.

The late-Victorian story was about aliens — Cokinos noted in an email that those aliens were “killed by the common cold” — but the descent of society followed the same structure as most zombie stories and Thucydides’ historical account of the Plague of Thebes.

Among pandemic fiction and the histories that inspired them, imagery of societal descent, the deaths of health workers and mass graves are prevalent. Another common denominator is the hunt for a scapegoat, according to Selisker.

“Something about the contagion narrative is that we’re always looking for something or someone to blame,” Selisker said. “Even though we’re seeing pictures of the COVID-19 virus … it seems remarkably widespread an idea that there needs to be something to blame. I’ve seen among colleagues of mine elsewhere an uptick in slurs hurled at Asian Americans and xenophobia centered around China.”

Selisker noted the historical example of Mary Mallon, also known as “Typhoid Mary.” According to Encyclopædia Britannica, she was an Irish immigrant believed to have infected 51 people with typhoid fever after the U.S. identified her as an asymptomatic carrier. She was forcibly isolated and died in her isolation after three decades.

“Just because she was a healthy carrier, she was demonized in the media as someone who was spreading the disease,” Selisker said. “The same goes for the search for patient zero that happened with HIV/AIDS in the 80s.”

The historical accounts of governments’ inadequate responses to impending global catastrophe make their way into fiction rather easily, but Cokinos noted that the narrative of failed response is often rather uninventive.

“What the genre has not succeeded in, largely, is showing us possible paths to organize and govern ourselves at the large population scale we have,” Cokinos said in an email. “That lack may be in part because it’s more dramatic to have a plague or nuclear war kill off a lot of people and in part due to the inherent lack of narrative interest in thinking about, of all things, bureaucracy.”

The recent global response to COVID-19, as well as the U.S. response, has brought many decisions under scrutiny. Selisker believes that “epidemiologists have been telling us to do new things for quite some time,” in the wake of SARS and Ebola. But what they have to say isn’t always “good news,” Selisker said, and “policy makers seem to not always find it expedient to follow [the epidemiologists’] advice.”

Even Cokinos noted that “the failure to have a national testing strategy, to pick just one U.S. failure, results in tragedy.”

If historical accounts of the Plague of Thebes, the Bubonic Plague, the Spanish Flu, SARS and H1N1 influenced so much fiction, it would follow that there is something about disease response and cultural change that could be gleaned from reading science fiction. Selisker hopes that his students recognize that COVID-19 has a “Before” and an “After,” and incorporate this into their contemporary analysis.

According to Cokinos, the same cannot be expected of policy makers.

“It’s the case that engineers and scientists read a lot of science fiction. It’s too bad most politicians don’t,” Cokinos said in an email.

At its core, science fiction is “a literature of ideas,” Cokinos wrote. And as Selisker explained, those ideas are easier to digest from a TV screen or the pages of a book.

“I think what’s really special about science fiction is it takes historical or natural novelties and helps to digest them, to think them through,” Selisker said.

He is sure, in light of the “After” of COVID-19, that art, culture and literature will experience a natural shift as a response to the necessity of understanding this event. What can be learned from them, we can only wait to discover.

“One of the things I think about as a literary scholar is what sort of narrative frames we use to imagine and understand the impact of a virus like [COVID-19],” Selisker said. “What does this event mean to us as a culture? This genre is a way of coming to grips with what is, in many ways, a novel event in contemporary culture.”

Follow the Daily Wildcat on Twitter