Mary Ayala, a student at the UA College of Architecture, has been taking one class every semester for the past two years. Like many undocumented students in Tucson, Ayala, whose name has been changed to maintain anonymity, has to go to school as an out-of-state student and pay out of pocket, causing her to finish her architecture degree in about 10 years instead of five.

“My senior year I received so many scholarships, full ride scholarships that I just couldn’t take because I didn’t have a social (security number),” Ayala said.

On June 15, President Barack Obama announced that young people who meet certain qualifications would qualify for a two-year work permit that they could then renew every two years. This temporary administrative relief could provide thousands of young people with the opportunity to remain in the country after completing higher education.

Scholarships A-Z, an organization that provides students a list of private scholarships regardless of immigration status, decided to clarify the ramifications of Obama’s announcement by holding a press conference for the community. Parents, high school students and college students who attended the conference had questions about how procedures had changed for releasing someone who was detained, but was eligible for administrative relief. They also asked about the criteria for work-permit eligibility.

“We still don’t have all the information and like we have said, it’ll be case by case but the best thing we can do right now is be enrolled in school,” said Ayala.

Ayala moved to Tucson in second grade, and has since faced many difficulties growing up undocumented in the United States.

“My roots are here. My friends are here and my whole family is here,” she said.

With the help of a private scholarship, Ayala was able to attend Pima Community College full-time after high school and graduated a semester early. During her last semester at Pima, she dually enrolled at the UA as an out-of-state student, paying about $6,000 out of pocket each semester for a year.

In November 2006, voters in Arizona passed Proposition 300, a law stating that a student had to prove that they were in the U.S. legally in order to be granted in-state tuition or government financial aid.

“It doesn’t mean that Proposition 300 doesn’t allow you to go to school because that’s a misconception,” Ayala said. “But we’re just priced out of school.”

Still, she enrolled full-time, and also took a full-time job doing inventory for a small company in order to pay for school. After a year of going back and forth between work and school, she got sick. She then quit work and decided to take one class every semester, paying about $3,500 per semester.

It was hard to find money for food, gas and even school materials, Ayala said. Spending hours calculating what she could and couldn’t afford for class projects was confusing, she added.

“I’d buy the worst in materials and I had to build the best of them to get the grade,” she said.

Now a wellness coach, Ayala is managing one class per semester. She also stayed involved with Scholarships A-Z, which she said inspires her to keep going.

“So it was tough but … I know that one day, when it’s all over and I have my degree, it’s going to be something inspirational for another person that’s going through the same thing,” Ayala said.

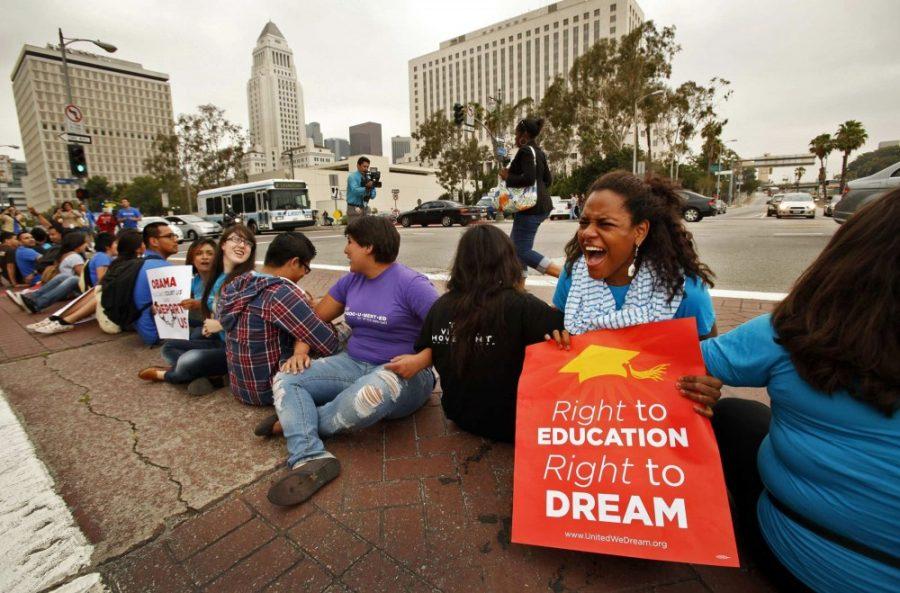

While Obama’s deferred action announcement may be a step forward for undocumented immigrants, more needs to be done so students can go to school, Ayala added. In his speech on June 15, Obama said, “This is not amnesty. This is not immunity. This is not a path to citizenship. It’s not a permanent fix.”

“It’s something that could end anytime,” Ayala said. “So basically this is just like tied to him … So what if he doesn’t get reelected? Our students and our community can’t be living in two-year increments … We still have to push for the DREAM Act.”

Denia Silva, an undocumented Tucson resident who can’t yet afford college tuition, believes the work permit is still helpful, because those who qualify can now get a better job that will help them pay the high tuition.

“Once … I get those papers in my hand that I can work, then I can just be free for two years, Silva said. “The whole time, my 22 years I’ve felt like I’ve been in a jail pretty much.”

Silva came to Tucson when she was 1-year-old. She always wanted to go to college, she said, but when she got to high school and learned about anti-immigration laws, she lost hope and stopped trying.

“I don’t even know what the border looks like,” Silva said. “I think I deserve to be here.”

Silva said she’s always been scared of police officers and any higher authority, including high school teachers. Since she was young, her mother warned her of what not to say around police in order to avoid deportation. It wasn’t until recently Silva began to drive, and when she does, she’s extremely cautious of traffic laws.

While Silva is happy with Obama’s deferred action announcement, she still thinks more should be done. Passing the act would help those living here undocumented who already consider themselves American, Silva said.

“The DREAM Act, that can’t (negatively) affect America in any way,” Silva said. “They’re getting people to go to college or to join a military branch. Which either or is a benefit to the country. It’s conditioned, which is helpful to everybody.”

Adelina Lopez, a sophomore at Pima Community College, is also looking forward to qualifying for Obama’s administrative relief.

“I will for the first time apply for a job,” Lopez said. “I will be provided a Social Security number, which I’ve never had before.”

Lopez takes one class per semester and makes some money babysitting in order to pay bills. Like Silva, she believes that a better job will help her be able to afford school.

“Of course it’s a step forward, and of course it benefits millions of people,” Silva added. “It’s a life-changing decision that he made for millions of people.”