ORLANDO, Fla. – With the future of its famous killer-whale shows at risk, SeaWorld Entertainment Inc. on Tuesday will resume its more than 3-year-old legal war with the federal government over whether trainers should be allowed to perform alongside the giant predators.

The stakes are higher than ever for SeaWorld, which will plead its case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, often called the second-highest court in the nation.

Orlando-based SeaWorld has asked the court to overturn a citation issued by workplace-safety investigators, who accused SeaWorld of willfully putting its animal trainers in danger and recommended that the trainers never again be permitted to perform in close, unprotected contact with killer whales.

The company, which owns marine parks in Orlando, California and Texas, accuses the government of overreaching and says the case could reverberate far beyond its orca pools.

Allowing regulators to bar close contact between whales and trainers, the company argues in legal filings, would mean giving them the power to force a company to change the fundamental nature of its business. SeaWorld likens the restriction to requiring speed limits in NASCAR races or forbidding tackling in the National Football League.

In making its case, SeaWorld lays out in unusually stark terms how much it depends on the thrills that come from putting humans and killer whales together.

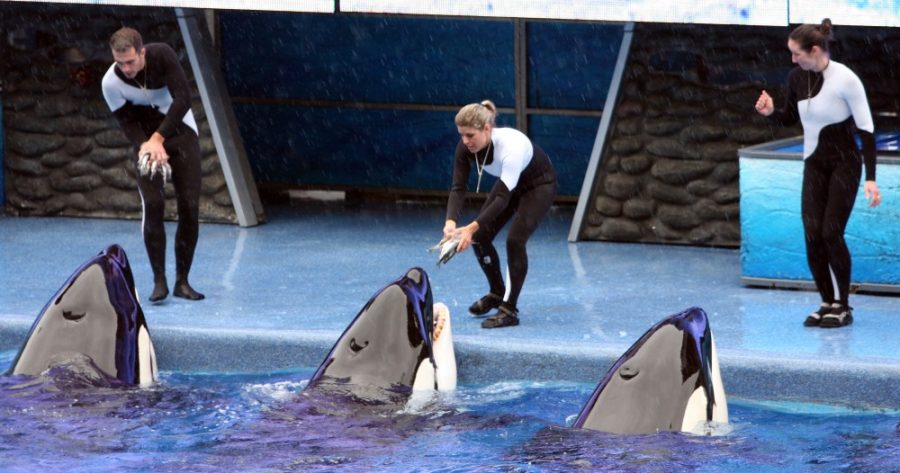

“The record in this case reveals that ‘close contact’ with killer whales is essential to the product offered by SeaWorld, and is indeed the primary reason trainers and audiences have been drawn to SeaWorld for nearly 50 years,” lawyers for the company wrote in a brief.

The case has its roots in tragedy. On Feb. 24, 2010, the company’s biggest killer whale – a 6-ton male named Tilikum at SeaWorld Orlando – pulled veteran trainer Dawn Brancheau into a tank and killed her. Tilikum had been involved in two earlier human deaths.

SeaWorld, which immediately stopped all “water work” between trainers and whales, has spent millions researching and designing new safety features, including emergency lift floors that could be used to quickly pull a trainer and whale out of the water. One has been installed at SeaWorld Orlando, another is under construction at SeaWorld San Diego and a third is planned for SeaWorld San Antonio.

But the company continues to endure scathing publicity, most notably from “Blackfish,” a documentary film that chronicles the capture and captivity of Tilikum. The film appeared in theaters around the country during the summer and has been broadcast on CNN.

And it is still battling the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which spent six months investigating SeaWorld’s safety practices after Brancheau’s death. The agency concluded that SeaWorld trainers should not be permitted to perform with killer whales unless protected by a physical barrier or sufficient distance – a standard that would make it impossible for them to swim with the animals.

The case involves some of the country’s most prominent legal figures. The three-judge panel that will hear SeaWorld’s appeal Tuesday will include Chief Judge Merrick Garland, a 1997 appointee of Democratic President Bill Clinton who was on President Barack Obama’s short list in 2010 for a nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court. The other two judges are Judith Rogers, appointed in 1994 by Clinton, and Brett Kavanaugh, named in 2006 by President George W. Bush.

To make its case, SeaWorld has hired Eugene Scalia, the son of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and a former top lawyer for the U.S. Department of Labor, the federal agency that includes OSHA.

OSHA contends that requiring barriers or distance between trainers and whales is a reasonable safety concession – and hardly something that would upend SeaWorld’s business. The agency points out that SeaWorld has already designed an entirely new killer-whale show, the 2-year-old “One Ocean,” that does not incorporate water work.

“Both measures (barriers and distance) operate under the common-sense proposition that keeping trainers out of reach of the whales will prevent whales from grabbing or contacting trainers, thus materially reducing – even eliminating – the risk of deaths or serious injuries,” lawyers for OSHA wrote in their brief.

By contesting the scope of OSHA’s power, SeaWorld is making a rare legal argument, said Arthur G. Sapper, a partner in the Washington, D.C., firm McDermott Will & Emery who specializes in OSHA law. But it’s possible the court may choose to ignore that issue and make a decision on factors specific to this case.

“The judges will probably ask themselves whether they can decide the case on a narrow ground without reaching the argument” about OSHA’s power, Sapper said. “Courts generally don’t decide unusual or broad issues if they don’t have to.”