Pluto was stripped of its planetary status yesterday in a controversial decision made by the International Astronomical Union that has raised mixed reactions among the UA scientific community.

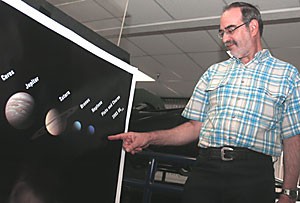

Larry Lebofsky, a senior research scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and member of IAU, said that he is “”less than pleased”” with the decision.

“”From a scientific point of view, I sort of think it makes sense. … From an educational point of view, I wonder why Pluto couldn’t be grandfathered in,”” Lebofsky said. “”I am not totally thrilled with the result. Part of it is a personal bias, part of it is from an educational perspective, but I do not think it was a good thing to do.””

Thomas Fleming, an associate astronomer in Steward Observatory who is also a member of IAU, said he was opposed to Pluto being grandfathered in on the grounds that, “”when it comes to science, there is no place for sentimentality.””

The other possible outcome of the vote would have been to give our solar system 12 planets – making Ceres, 2003-UB-313 (otherwise known as Xena) and Charon all planets and not changing the status of Pluto.

Lebofsky, who favored the 12-planet model, said part of the reason the model was vetoed was because some scientists believe this would lead to too many outer solar system objects being classified as planets. With too many additional planets, each could lose their individual significance and scientists might spend less time studying them, Lebofsky said.

Catherine Neish, a planetary sciences graduate student studying Jupiter, said the opposite could also hold true because if it is not a planet, scientists might not be as interested in studying it.

“”They won’t be like, ‘Ah, we’re going to the ninth planet.’ No, it’ll be, ‘Oh, we’re going to a Kuiper Belt member,'”” Neish said. “”But I hope that’s not the case because asteroids and Kuiper Belt objects are really important in telling us about the origin of the solar system.””

Fleming, said the decision was the right one to make because this situation has happened before.

When Ceres, an asteroid, was discovered, it was also called a planet, along with four other asteroids that were discovered later.

This lasted for 50 years, but the IAU decided there were too many planets so it decided to call them asteroids, Fleming said.

The new IAU definition of a planet is that it must be an object that is self-gravitating, spherical and orbiting a star and has a strong enough gravitational force to clear the path of its own orbit. This means any object in its orbit must either be a moon or be following in its path, but not orbiting in the same path on its own, Fleming said.

The debate over Pluto began nearly two years ago when a panel of 19 scientists met in Cambridge, England. This year, a new panel met to discuss the issue further in Paris, Lebofsky said.

All of the 9,000 members of the IAU, including Lebofsky and Fleming, were invited to Prague, but only the scientists who attended the meeting were allowed to vote.

Fleming said he thought the decision to only let members appearing in person to vote was irritating.

Lebofsky said the decision was important because there needed to be a meaningful classification, which was not in place before. This will help scientists do more concise research on objects found in the universe and their evolution, Lebofsky said.

However, this system is not like the Fahrenheit degree system or the metric system because as widely used as both of these are, they are not international. This new system is international, making it more significant.

“”Scientists are united … under one organization that makes the rules. It is not the U.S. telling the rest of the world that what we say is law,”” Lebofsky said. “”It is the IAU that oversees the naming of asteroids, comets, satellites of other planets and now planets. We all abide by these rules.””