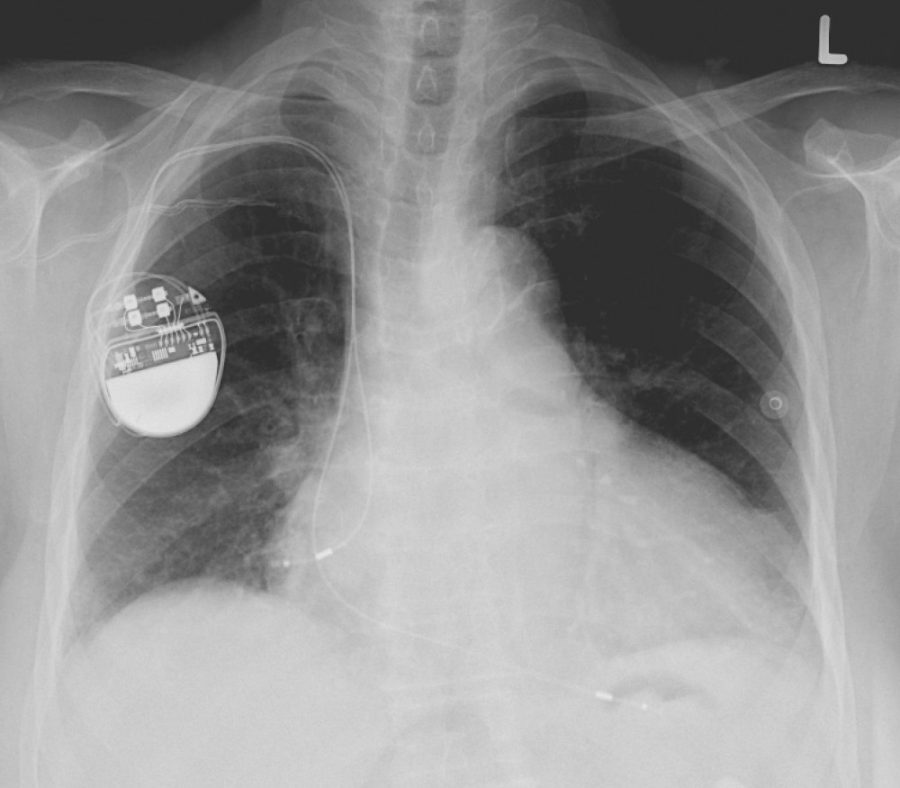

Dr. Christian Dameff and Dr. Jeff Tully, graduates of the UA College of Medicine in Phoenix, recently hosted a summit on the threat of computer hacking aimed at hospitals and medical devices. With modern medicine relying so much on technology like insulin pumps, pacemakers and electronic medical records, an instance of malicious hacking could be lethal.

While hackers are often perceived as lone malcontents in hoodies furiously typing away on computers in darkened rooms, Dameff cautioned against applying the stereotype universally.

“In actuality, hackers are individuals who understand the system to such a degree that they can identify weaknesses,” Dameff said, explaining that he identifies as a hacker. “When I was young, one of my friends got a computer, and he started showing me this whole new world, and when I look back now it’s the foundation of why I call myself a hacker.”

The hackers we have to worry about are called “black hats.” They’re individuals with malicious intent who hack things for their own personal gain. “White hats,” in contrast, hack to expose security vulnerabilities so that computers and networks can be toughened, before being released susceptible to exploitation for nefarious purposes. Dameff became interested in this kind of ethical hacking.

RELATED: Healthcare in the age of Trump: Your medicine and you

From an early age, Dameff immersed himself in hacker culture and knowledge.

“I lived two lives, where my formal education was in medicine — and because of this, I was able to take my knowledge of hacking and apply it towards medicine,” he said.

A specific incident spurred Dameff’s thinking about hacking and medicine. “I was listening to some 911 calls on cardiac arrest for some of my studies, and I thought to myself, what would happen if 911 went down?”

Dameff and Tully decided to start researching the viability of hacking 911, only to realize it isn’t as difficult as it should be. After presenting their work at DEF CON, a yearly hacking convention held in Las Vegas, Dameff decided to merge his two worlds of hacking and medicine.

Dameff described the difficulty of dealing with instances of medical hacking.

“If measles breaks out in Tucson, the Centers for Disease Control will be there in less than 10 hours,” he said, “but we don’t have any system to determine whether or not medical devices have been hacked.”

We know that hacking of pacemakers and insulin pumps is possible because New Zealand hacker and computer security expert Barnaby Jack demonstrated it. So, while no hacking of these devices has been reported outside of his tests, we know it can be done. And there have already been other types of medical hacking incidents reported across the globe.

In May, the United Kingdom suffered a ransomware attack that crippled their health care and hospital systems. A simple virus attached to an email locked critical files and information on computers and demanded $300 in bitcoin from each user. This simple Trojan horse shut down dozens of hospitals across the country.

The malware used to get into the hospital systems was actually an exploit discovered by the NSA that got leaked and weaponized. Microsoft had fixed the problem in a patch, but many organizations are either slow to apply updates or run their computers on older versions of the Windows operating system.

“This is the case that has received the most attention, but this is not the beginning,” Dameff said.

RELATED: CRISPR gene editing tech brings countless opportunities and challenges

California’s Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital was hit with a ransomware attack last year in February, eventually paying $17,000 in bitcoin to the attackers. The hospital was shut down for days as a result, and several patients were deprived of health care.

“Health care is fragile, patient care is fragile, because we rely so much on technical infrastructure” Dameff observed.

Dameff and Tully believe that hospitals need more updated equipment running later and more secure operating systems — as well as experts dedicated to keeping all the technology in check.

“I work at a hospital, and say I need a CT scanner. If I don’t have the money, I’ll buy a scanner that’s 6 or 7 years old,” Dameff said.

These older pieces of technology may run on older operating systems, making them vulnerable to attack.

“I don’t want people to not get pacemakers, not get insulin pumps, and not go to the hospital because they’re afraid they’ll get hacked,” Dameff said. “But we need to raise awareness without being alarmist, and get the attention of policymakers.”

Follow William Rockwell on Twitter.