UA faculty members are looking for ways to preserve and revitalize endangered languages in an effort to help students of minority cultures keep their heritage alive. The purpose is to break a cycle of knowledge loss that occurs when children enter schools and learn English, instead of their traditional languages.

Nutritional science junior Liz Francisco’s mother used to speak O’odham, a language traditionally spoken by the Tohono O’odham tribe. However, she stopped speaking it at her grandmother’s request.

“Tradition is mostly lost,” Francisco said. “The only real tradition I know of is storytelling and round dancing.”

In an effort to regain her sense of culture, Francisco enrolled herself in a Tohono O’odham related course.

Now, UA faculty members are trying to help students like Francisco immerse themselves in their heritage. It is challenging in today’s busy modern world, but UA began the critical languagesprogram to increase the number of students learning less common languages.

RELATED: UA continues working to include large Hispanic community

Malcolm Compitello, head of the Spanish and Portuguese program, notes learning an endangered language can make students more employable in the future and advises students to combine what they want to learn a language.

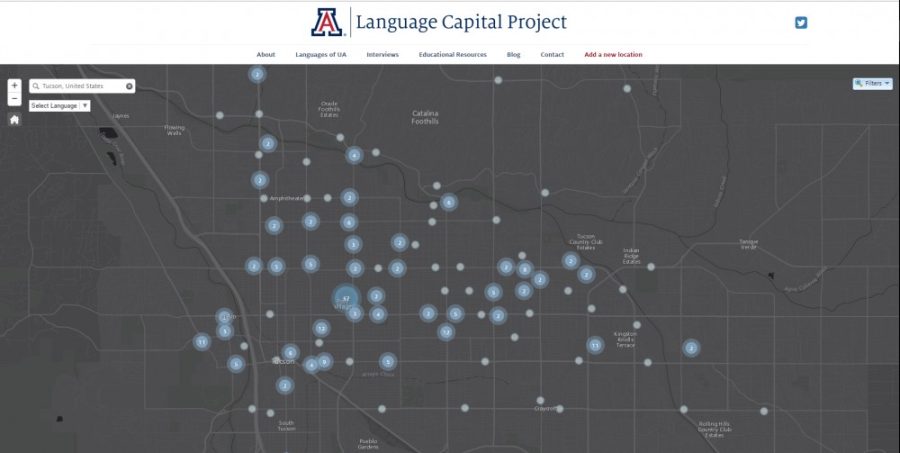

When learning a minority language, finding others to learn with may be a challenge, however, Christian Ruvalcaba, graduate fellow with the UA Confluencenter for Creative Inquiry, started the Language Capital Project which is a website to connect nonnative speakers to one another.

The goal is to change the trend by giving uncommon languages a bigger spotlight, while encouraging American-born students to learn a language. All members of the UA community can participate.

“We want to highlight the language and cultural diversity that thrives here,” Ruvalcaba said.

Ruvalcaba also said the languages available in media can send subtle messages to speakers, which can contribute to cultural dissolving.

“We can go an extra step and possibly have columns or whole newspapers dedicated to the news utilizing different minority languages,” Ruvalcaba said. “Our university online news sites only use English language and have no options for other language viewing.”

RELATED: Arizona State Museum unveils new Native American basketweaving exhibit

According to Ruvalcaba, acknowledging and using other languages may help keep minority languages relevant.

“Parents can designate their heritage language as the sole language used within the home,” Ruvalcaba said. “Maintaining and holding firm to language policies in the home is very effective.”

Languages have difficulty surviving in other countries where they are not traditionally spoken. Ruvalcaba said this is due to the perception of a language’s country of origin and speakers of minority languages’ eagerness to adopt English.

“While a parent might value the heritage language, they also want to make sure their child is able to succeed in this country as fast as possible,” Ruvalcaba said. “[An] important issue is figuring out a way to dispel the idea that multilingualism is un-American or unusual.”

Ruvalcaba said any time is the right time for someone to immerse themselves in a culture and that knowing a language is not a prerequisite to be a part of that culture.

“‘Catching up’ is the wrong way to look at both language and culture,” Ruvalcaba said. “It suggests that they are not already practicing their culture.”

Compitello said he looks at endangered languages the same way he does Spanish: as a skill that anyone can learn. However, he advises students to take foreign language seriously and to do what is best for them.

“Expand your knowledge in a way that will allow you to make an impact on other people,” Compitello said.

Follow Phil Bramwell on Twitter.