Correction: The Dec. 1 story “”Genome project traces human history”” misused the word “”genome”” in the headline, as The Genographic Project does not deal with genomes. The story also erroneously referred to the “”Anderson”” sequence as the reference for sample DNA. The reference sequence used is actually the Cambridge reference sequence (CRS). The Daily Wildcat regrets the errors.

While reporting on The Genographic Project at the UA’s Arizona Research Laboratories, Daily Wildcat reporter Carly Kennedy was given the opportunity to have her own family history traced through genome sequencing.

Our name, our hair color, our native language, our ethnic heritage, our inherited family name and other basic characteristics differentiate each human from the other.

Although we are different at first glace, just scratch the surface a little and modern DNA testing can unveil an individual’s connection to the entire human family tree.

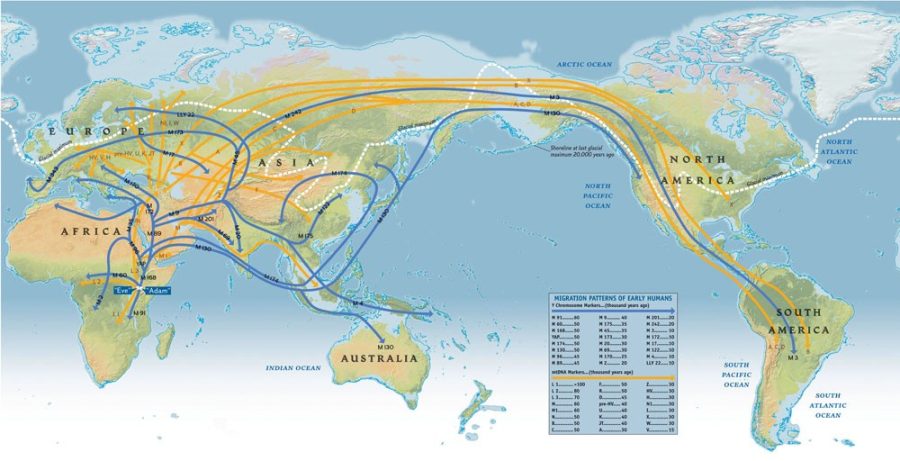

It is widely accepted in the scientific world that each human on earth is the relative of a group of people who lived in Africa — as recently as 2,000 generations ago.

Fifteen years ago, researchers began compiling DNA samples around the world to help obtain the ambitious goal of piecing together the human family tree and our ancestors’ journey out of Africa.

They modeled their research after the work of geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, the grandfather of human DNA testing. Sforza knew that remote populations, like isolated tribes in Africa, Asia and Australia, could provide a clearer picture of the human family tree.

After traveling the world to remote areas and taking blood samples from the native peoples, geneticists have traced our ancestors’ movements throughout the world, and the time frame for each migration.

National Geographic has since opened up the human DNA testing to the public, an effort known as The Genographic Project, and the UA serves as the organization’s human testing lab. The UA has been doing human DNA testing since 1999, and was chosen by National Geographic because of it’s proven expertise in the area.

Given that the resources were close and The Genographic Project is so intriguing, the opportunity to participate was impossible for me to pass up.

Arizona Research Labs provided me with a kit containing two swabs, two containers filled with a clear liquid and instructions.

It was simple enough: I rubbed the inside of my cheek for several seconds with the swab and removed the tip of the swab into the liquid-filled container.

Next, I chose what lineage I would like to follow: my mother’s or father’s. I chose my mother’s so I followed my mitochondrial line. I then shipped off my package of materials to National Geographic and waited for my samples to be received in the lab.

After the batch is received by the lab, the cells in each sample are broken open by an enzyme that chews up the protein and exposes the DNA, and then incubated at 55 degrees Celsius overnight, explained Taylor Edwards, assistant staff specialist at Arizona Research Labs.

The next day, the samples are placed into deep well blocks for DNA extraction performed by a robot. DNA likes to stick to a chemical known as silica — so the robot attaches silica-coated iron beads to the sample. The DNA sticks to it, and it is pulled out using a magnet attracted to the iron.

Once the DNA is separated from the silica beads, the DNA is then moved to additional testing stations. Different chemicals are added to target different regions of the DNA, and after the samples are heated and cooled, they are loaded into the capillary electrophoresis machine.

“”The capillary electrophoresis machine reads the DNA and each base pair gets a different color,”” Edwards said. “”From this, we are able to actually visualize a single strand of mitochondrial DNA.””

Using a computer program, lab staff analyzes 500 base pairs of DNA to find the differences when compared to a sample DNA strand — known as the Anderson DNA.

Edwards explained that Anderson is not an actual person, but it’s the average “”white-guy”” DNA. Scientists use Anderson to help analyze the received samples because researchers need something to help judge the amount of mutations, or glitches in the strand. This will in-turn help them place the sample into a haplogroup.

Because of the large amount of DNA samples the lab receives each day, it takes roughly 10 days after receiving the DNA to get it to analysis, said Edwards.

After researchers confirm the amount of mutations I have from Anderson, my results are posted.

My results: My mitochondrial DNA differs from the reference sequence in the following places: 16153A, 16311C. Meaning my DNA is two mutations away from the Anderson DNA.

The mutations in the mitochondria, are passed down from mother to daughter for generations — and geneticists use the mutations as markers to help construct the mitochondrial family tree.

The two mutations make me a member to the branch of the family tree known as Haplogroup HV*.

My family’s journey: about 30,000 years ago, my family moved from what is present-day Turkey, over the Caucasus Mountains into Europe. Better weapons, communication skills and resourcefulness helped my ancestors out-compete the Neanderthals that originally inhabited Europe.

When the ice sheets that covered northern Europe began to recede 15,000 years ago, groups of human populations began to move up from warmer climates, like present-day Italy, and colonize northern Europe. My family was part of that migration.

The H and V lineages make up 75 percent of all European DNA lines, the Genographic results explained. My DNA results agree with my German/Scottish heritage — so, Genographic team members were right on the money.

The Genographic Project can be found at Nationalgeographic.com and testing kits can be sent to an individual on demand.

“”The Human Genographic Project shows us that although we look different, we all come from the same family tree,”” said Edwards. “”Which really is quite unifying.””