The best thing about this film may well be its title. It was a stroke of genius to call this often pointed, sometimes sentimental documentary “”The U.S. vs. John Lennon.””

The film is about exactly what the title promises: For one crazy moment in time, the United States, the most powerful nation on the planet, considered a daffy, loudmouth rock star a serious threat.

The filmmakers’ sentimentality is evident in their view of Lennon, who is depicted as nothing short of a saint. But the film’s pointedness emerges in its treatment of the Vietnam War, and the popular dissent that finally forced an end to that conflict.

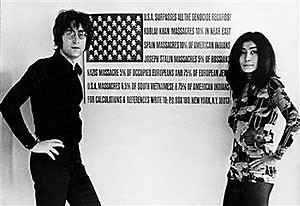

“”The U.S. vs. John Lennon”” begins in 1966, when Lennon first openly declared his opposition to Vietnam (soon after his notorious offhand remark “”We’re more popular than Jesus now””). But Lennon’s activism didn’t fully take off until he met oddball Japanese artist Yoko Ono.

Ono has (unfairly) gone down in history as the woman who broke up The Beatles. Even if that charge were true, we’re probably better off living in a universe where John Lennon wrote “”Imagine”” than a universe where The Beatles followed the example of every other great band and put out 30 more increasingly disappointing albums.

Lennon’s activism soon turned deadly serious. After moving to the U.S., he started using his fame to campaign against President Richard Nixon, who was running for re-election. It was 1972, and the voting age had just been lowered to 18, meaning Nixon would have to win over 11 million new voters at a time when more young Americans were politically active than ever before.

Lennon got the same treatment as Nixon’s other enemies. He was shadowed by FBI agents, had his phone tapped and finally found himself facing deportation. He spent three years fighting it, and his activism fell by the wayside.

The film could have been tightened up a little. We get a few too many shots of John and Yoko gazing adoringly at each other. The hard facts of Lennon’s court case are not explained very well.

But the soundtrack is littered with gems from Lennon’s brilliant solo work, from the hard-rocking “”New York City”” to the scathing “”Instant Karma!”” A haunting photo montage sets “”Imagine”” to a series of grim shots of Vietnam, reminding us that Lennon wrote his famous peace anthem at the height of a brutal and immoral war.

The film doesn’t skimp on Lennon and Ono’s early “”media events,”” which were bizarre enough to make Michael Jackson seem boring: holding an entire press conference from inside a large bag, for example, or announcing that they’ve formed their own country, “”Neutopia.””

In one memorable clip, Lennon argues furiously with reporter Gloria Emerson, who insists that his “”ridiculous”” antics are undermining the anti-war movement. One feels that Emerson had a point. But when we see thousands of protesters outside the White House singing “”Give Peace a Chance,”” Lennon’s somewhat slapdash spontaneous anthem, it’s breathtaking.

‘The U.S. vs. John Lennon’

PG-13

96 minutes

Lions’ Gate Films

8/10

You’re struck by the impact this most unlikely of heroes had on the world. It’s hard to imagine any of today’s pop stars inspiring an entire movement.

Making the case for the prosecution is former Nixon henchman G. Gordon Liddy, who boasts about using a protester’s candle to light his cigar and matter-of-factly insists that Lennon was a threat to “”stability at home.”” Liddy comes across as almost comically mean, relishing the role of the sole dissenter at the party.

“”The U.S. vs. John Lennon”” ends on a bittersweet note, with Lennon winning the right to stay in the U.S. and celebrating with his wife and newborn son. The viewer, of course, knows that this happiness will not last; four years later, Lennon was shot by a demented stalker. The film does not linger over a sad irony: If Lennon had been evicted from the U.S., he might well be alive today.

The last word belongs to historian Gore Vidal. “”He represented life,”” Vidal declares of Lennon. “”Mr. Nixon and Mr. Bush represent death.””