Other than “Bear Down!”, you may have heard the University of Arizona’s harping on its status as a land-grant institution. But what does that mean and what does it look like for the UA School of Plant Sciences?

Origins

Being a land-grant university dates back to the Morrill Land Grant College Act of 1862, a few years before the University of Arizona’s establishment in 1885. This act granted states 30,000 acres of land to create colleges to “benefit the agricultural and mechanical arts.”

This means that the research done at the UA is focused on addressing the problems or needs of the state in a practical way through agriculture and mining. In the early years, most research was focused on creating an economic base. However, as the population exploded in the 20th century through urbanization, the University of Arizona shifted to address this new strain on natural resources by focusing on landscape ornamentals, which are aesthetically pleasing plants that can be grown as part of a green space in urban areas.

UA Campus Arboretum

This shift in research can be seen all around campus. When one walks around the university, it’s hard not to notice the greenery, or gravitate toward the cool shades of the shrubbery. The entire university is considered a garden of trees – an arboretum.

Each tree contributes to the UA Campus Arboretum, which has seen major changes over the years. When the university first began, the arboretum focused on seeing which cash crops could thrive in the semi-arid desert. Date palms, citrus and olive trees were proven to be successful experiments.

Then, as the population of Arizona grew, landscape ornamentals became the central focus, successfully introducing plants from around the world to campus. Researchers wanted to improve the aesthetics and minimize the impacts of the growing urban landscape. The Monk’s Pepper tree, native to the Mediterranean, and the Jacaranda tree, native to tropical regions of the Americas, were among some of the hundreds planted.

“If we have a lot of variety of living plants, it essentially means we minimize the risk,” UA Campus Arboretum Director Tanya Quist said.

This biodiversity can contribute to a resilient environment – if one plant fails due to a change in climate, there will be many others that are suited to fill the gap and pick up the slack, according to Quist.

The UA Campus Arboretum director said the garden is now entering a new, third phase with the goal of influencing sustainable practices in an urban landscape.

“We want those amazing, high-performing plants here as a model to the community about trying these plants or growing these plants,” Quist said.

Rubber in Arizona

Still, that doesn’t mean that research is no longer being done to bolster economic growth in Arizona. Dennis T. Ray, a University Distinguished professor in the School of Plant Sciences, uses the institution’s land to see which crops and products can be cultivated in the arid environment.

One plant he researches is something we’re familiar with seeing every day on our cars: the guayule plant, which produces rubber. As the population grows, there is not enough rubber being grown in areas like Northern Mexico, where this crop has traditionally been exported from. With this in mind, Ray’s research looks into how rubber yields could be improved.

In 2004, he was part of research that yielded 250% more rubber compared to the mid-20th century. Ray continues to study guayule improvement and speeding up the breeding progress of these plants today.

With this research, “huge acreages of guayule in central Arizona” may be introduced, according to Ray.

Greenhouse crops and grass

There is also research being done to improve the experience right under our feet: Mohammad Pessarakli, a research professor in the School of Plant Sciences, is continually researching the effect of stress on plants and grass.

In 2006, he set out to find what plant would be the most tolerant to stresses from climate change, like drought or salt levels. From testing 35 grass varieties, he found two were the most resilient to these changes. Now, according to Pessarakli, this research informs the type of Bermuda grass being used at the UA.

He also studies the effect of fertilizers and how much food and water plants like tomatoes, barley or wheat need.

As a researcher focused on stress physiology for plants, Pessarakli is constantly revising the Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress, as an editor of the book.

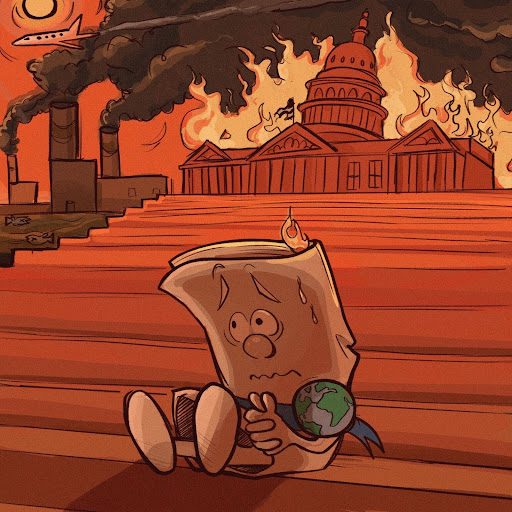

With environmental shifts due to climate change, he must now address how high and low temperatures, drought, salt content or pollution affects crops.

“Science is dynamic. Changes are all the time,” Pessarakli said.

Follow Sohi Kang on Twitter