No figure in American history continues to stir our imaginations more than Abraham Lincoln. Schoolchildren and historians alike revere “”The Great Emancipator,”” the man who saved the United States and freed the slaves, as our greatest president.

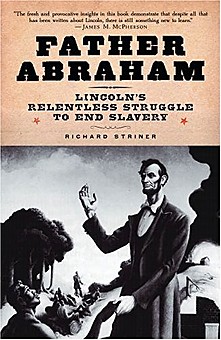

Why does Lincoln fascinate us? Perhaps because he is one of the few great leaders in history who seemed to act for good and noble reasons. In a time when even our better politicians seem stymied by a corrupt political establishment, Lincoln reminds us of our better nature. That is part of the thesis of Richard Striner’s excellent new book, “”Father Abraham: Lincoln’s Relentless Struggle to End Slavery.””

In recent years, though, Lincoln’s reputation has taken a battering. It has become fashionable to portray him as a tyrant who trampled over the rights of the Southern states and expanded the role of the president far beyond what the Founding Fathers ever imagined, paving the way for the excesses of modern presidents.

Most historians treat Lincoln more kindly, but they still downplay his heroism. As Striner notes, most chroniclers of Lincoln’s life portray him as a “”passive”” leader who had to be convinced of slavery’s wrongness. Lincoln’s sole intent was to save the Union, they insist.

Many of them point to a statement Lincoln made during the Civil War. “”If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could do it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that,”” he declared.

But remarks like these, Striner argues, give an incomplete picture of Lincoln’s beliefs, noting that he first came to the country’s attention as a firm opponent of slavery, an institution that many in the North were determined to end and the South was just as determined to keep.

As Striner shows, the Civil War could have been avoided if Lincoln had not wanted to end slavery. In December 1860, as war was about to break out, the Senate proposed a compromise which would have guaranteed the permanent existence of slavery in the Southern states and allowed it to spread, on a limited basis, among new states. Lincoln rejected it.

“”If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong,”” Lincoln wrote to a friend in 1864, adding, “”I cannot remember when I did not so think and feel.””

So why didn’t Lincoln openly admit that? Striner reminds us that Lincoln, like all democratic leaders, constantly had to justify the war to those who fought it. Like the lawyer he was, he had to bend the truth at times to convince his country that the war was worth fighting.

He also knew that, as president, he had no real authority to end slavery. But he was able to justify it as a military tactic, arguing that freeing the slaves would weaken the South. After his death, his example finally convinced Congress to abolish slavery for good.

One of the reasons Striner’s book is so convincing is that he depends largely on primary sources. He uses many of Lincoln’s letters and speeches from the 1850s to convince us of the young politician’s unshakable idealism. Striner writes: “”By itself, preservation of the Union was an empty concept to Lincoln, unless the Union remained dedicated – or could forcibly be re-dedicated – to its founding principle that all men are created equal.””

Striner’s argument is simple: Lincoln was a determined opponent of slavery who, for practical reasons, presented himself as a moderate. This strategy ultimately allowed him to do what no abolitionist had been able to do: end slavery.

But Lincoln’s strategy, Striner argues, has ironically harmed his reputation, as historians continue to insist that he was no radical.

The reasons for this myth’s lasting power are complex. In the decades after the Civil War, as racism became more widespread, Americans no longer wanted to remember a Lincoln who was opposed to slavery. They preferred to believe in a Lincoln who cared only about saving the Union.

Why do many people still accept this myth? Perhaps because we are so used to learning that our heroes are not really heroes at all, that all politicians act only out of pragmatic self-interest. But Striner’s book persuades us that there was, at least, one who did not.