It’s a frightening Tucson story many today aren’t familiar with — one involving teenagers, murder and the desert.

On June 1, 1964, the Arizona Daily Star’s headlining news was about the jailbreak that had occurred the day prior. “Seven Prisoners Stage Jailbreak In Tucson; All But One Captured” read the front page headline. Among other things in the paper that day were articles about the news in Tucson, Arizona and the world. However, not a single word was mentioned about Alleen Rowe, the 15-year-old Palo Verde High School student who had gone missing the night before. Police believed Rowe had run away after receiving a call from Rowe’s distraught mother, and they stuck with their story for over a year, finding no evidence to suggest otherwise.

“There are thousands of reasons why teenagers run away or leave home,” said Detective Sgt. Robert Wilhelm, in an article published in the Arizona Daily Star on Nov. 5, 1965. Wilhelm was head of the Missing Persons Detail of the Tucson Police Department.

According to “The Tucson Murders” by John Gilmore, Rowe was an intelligent student who worked hard and seemed to have a promising future ahead of her. She was well-behaved, got along with her divorced parents and her two brothers and seemed to be a happy teenager. Her disappearance simply didn’t add up.

Wilhelm’s article , titled “Four Tucson Teenage Girls Have Disappeared Into Thin Air,” discussed the disappearances of Gretchen and Wendy Fritz, Rowe and a fourth girl, Sandra Hughes, whose disappearance was later discovered to be unrelated. The four had gone missing at different times since Rowe vanished the year before, and while police believed otherwise, the parents of the Fritz sisters and Rowe were convinced their daughters had been murdered.

They were correct.

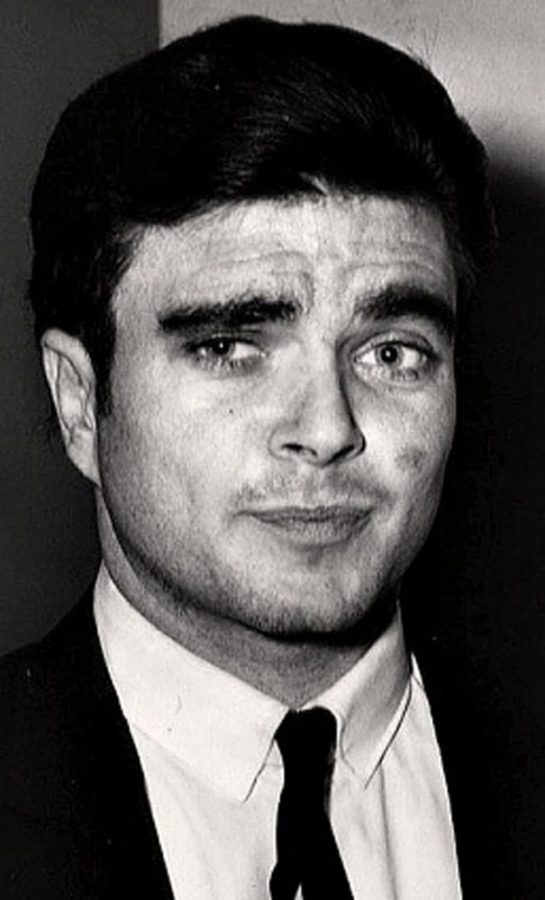

Charles Schmid was a man who, throughout high school, had always been a bit different. He dyed his hair often, wore makeup and had a habit of giving himself a birthmark on his face with axle grease. He wasn’t the best student and preferred to hang around Speedway Boulevard drinking with friends and driving around in the car his parents bought for him.

Schmid was known to be a compulsive liar, especially to women. He had lied to get girls to sleep with him, earning their sympathy by telling them he had leukemia as a child, was almost sold into slavery across the border, had a string of awful foster parents and cared for sick siblings. He was able to put on a convincing façade in front of parents; he was said to be courteous toward mothers and was considered a gentleman. There were a handful of small run-ins with the law, but nothing too severe. Other than a few eccentricities, Schmid seemed to be a relatively normal guy.

That changed after the bodies of the Fritz sisters were discovered.

Five days after the Arizona Daily Star article about them was published, the bodies of 17-year-old Gretchen Fritz and 13-year-old Wendy Fritz were discovered in the desert off Pontatoc Road after Richard Bruns, a former friend of Schmid, informed the police of their whereabouts.

Schmid had told Bruns about the murder about a month after it occurred, also confessing to the murder of Rowe. On May 30, 1964, Schmid told his friends he wanted to kill a girl to “see if he could get away with it,” according to various sources. He made a list of possible victims and decided on Rowe, then elicited help from his girlfriend and best friend, Mary French and John Saunders, respectively, to get Rowe to join the three on a double date. The four drove out to the desert where Schmid murdered her through blunt force from a large rock to the head, and Saunders helped him bury the body.

The three seemed to have covered up the murder, despite rumors circulating around the teenage crowds suggesting their guilt and Schmid’s lack of caring about being caught. A year later, while dating Gretchen Fritz, Schmid murdered her and her sister Wendy Fritz by strangulation.

After the Fritz sisters were discovered, Schmid was accused of three counts of murder and taken to trial. The Fritz sisters and Rowe cases garnered national attention. Life magazine had special coverage on the trial, and people across the nation kept up with the case. Schmid was dubbed the “Pied Piper of Tucson” by the media. Halfway through the Rowe trial, Schmid pleaded guilty to murdering Rowe and was sentenced 50 years to life in prison.

At the time of the verdict, however, Rowe’s body had still not been found, despite efforts by police, the incarcerated French and Saunders, and forensic investigators. On June 23, 1966, Schmid told the police he would show them where the victim’s remains were. He led the police out to the middle of the desert near Harrison Road, and, while handcuffed, dug up Rowe’s skull.Schmid claimed he led the police to his first victim’s body to prove he had strangled her to death rather than killed her with blunt force, but an examination of the remains showed a fractured skull.

Schmid’s sentence remained as it was, and he was originally on death row before the practice was temporarily abolished in Arizona in 1971. He made various escape attempts, one of which was temporarily successful, and continued to carry himself with an air of confidence and superiority. But his pride led to his death when he got in a fight with two fellow inmates and was found with 20 stab wounds, which proved to be fatal 10 days later.

It’s been 50 years since Rowe was murdered in the Tucson desert and 49 since the Fritz sisters suffered their fate. In that time, countless articles, fiction pieces and films have been created based on the horrific tale of the Tucson murders when three young girls had their lives cut short by a man who didn’t seem to understand his own motives.

_______________

Follow Victoria Pereira on Twitter.