Movie producers love to annihilate great works of literature. Words that took decades to shape are compressed into two hours of film: Now a debacle at a theater near you.

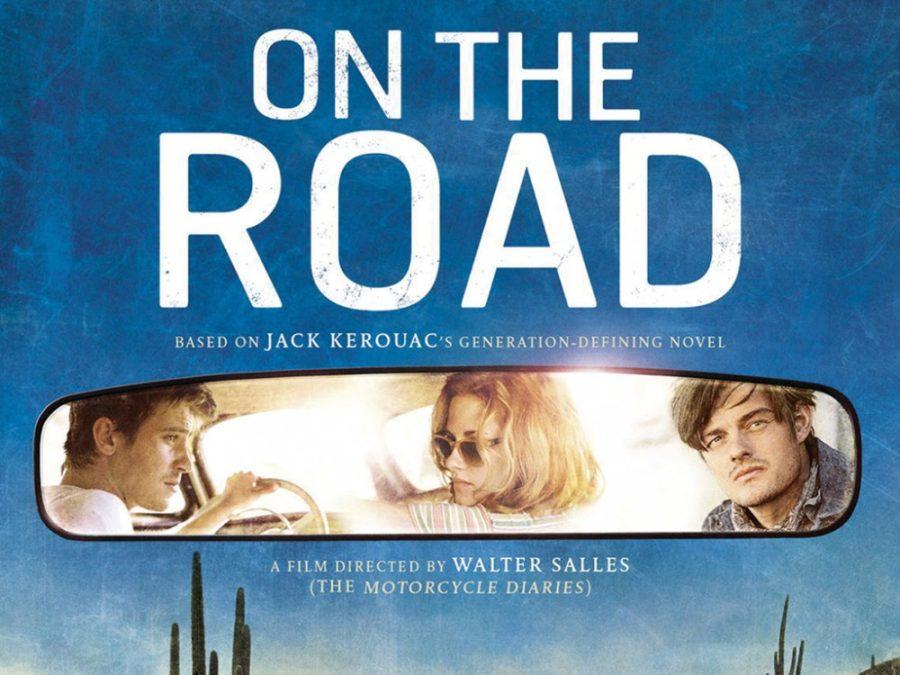

Adaptations can be acceptable sometimes — entertaining, even. But with the recent nationwide release of “On the Road,” a film based on the book of the same name by Jack Kerouac, it’s time to mourn the mangling of another novel.

Published in 1957, On the Road details the youthful abandon that Kerouac captures in his tale of wild cross-country travels. It is a story of frenetic drug use, inner turmoil, perpetual displacement and a fierce desire to live. The book is stark and raw.

The movie version is not remotely comparable.

“On the Road,” the film, feels like a yawn-worthy preview for some grand cinematic adventure yet to come. It is essentially the story of Dean and his relationship with Sal, but it lacks the visceral substance that can only come to life through Kerouac’s prose.

Beneath the overt themes of loveless sex, daddy issues and abandonment is a solid soundtrack and National Geographic-worthy stills. While the stills shine, the cinematography itself fails to capture the essence of Kerouac’s writing.

The film does, however, retain some semblance of the characters that fueled its creation. Tom Sturridge as Carlo Max, whose character is based on Kerouac’s friend Allen Ginsberg, delivers the most riveting performance the movie has to offer. Sam Riley plays Paradise, who is based on Kerouac himself, and Garrett Hedlund is the vivacious Moriarty, who Kerouac based on his actual companion on the road, Neal Cassady.

As a supporting actor to the antics of Paradise and Moriarty, Sturridge embodies the Ginsberg who graces the pages of the novel. His tumultuous soul comes across onscreen as the foil to Cassady’s underlying voice for the mad wanderlust that grips Kerouac and his friends.

However, the movie all but crams its erratic depiction of Moriarty down viewers’ throats. Anyone who hasn’t read the novel could easily miss that Moriarty is intended to embody the Beatnik generation.

Even with its inaccuracies, the movie does manage to convey these characters’ lost inhibitions and sense of abandonment. And to be sure, one of the film’s only redeeming quaities lies in its cinematic landscapes. Director Walter Salles lends rose-tinted glasses to life on the road as Kerouac and his pals drive wildly across the sprawling countryside.

One scene encompasses the movie’s atmosphere perfectly: Outside of Tucson, as the crew drives into the sun, the camera pans across the faces in the car. The trembling croon of one passenger breaks the silence, and in a rare moment of great acting, Kristen Stewart blinks back tears as Marylou. It’s endearing, capturing the sad and constant leaving behind that accompanies a life on the road. The movie is wonderful here — perhaps because no one is talking.

While this makes for a fine display of the film’s imagery, the vivid and radical description that Kerouac injected into On The Road is lost everywhere else. The basic characters and themes remain, but while the driving force of the book is its presentation of a vast American beauty, viewers of the film are left with little more than the occasional pretty picture.