A study conducted from 2005 to 2007 by UA researchers showed that permanent residents of the U.S. sometimes faced discrimination by local authorities in communities near the U.S.-Mexico border. Nearly 10 years later, the situation in these border communities may not be changing for these residents.

Dr. Samantha Sabo, an assistant professor in the department of health promotion sciences in the College of Public Health and the lead author of the study’s manuscript, said that “things haven’t improved” because there have been more anti-immigration laws passed since the conclusion of the study.

“I can’t say for sure, but I can only say that there’s been more severe laws that have been put into place and there’s been more money allocated to the Department of Homeland Security in terms of border immigration control,” Sabo said. “I would only assume that these things exist today.”

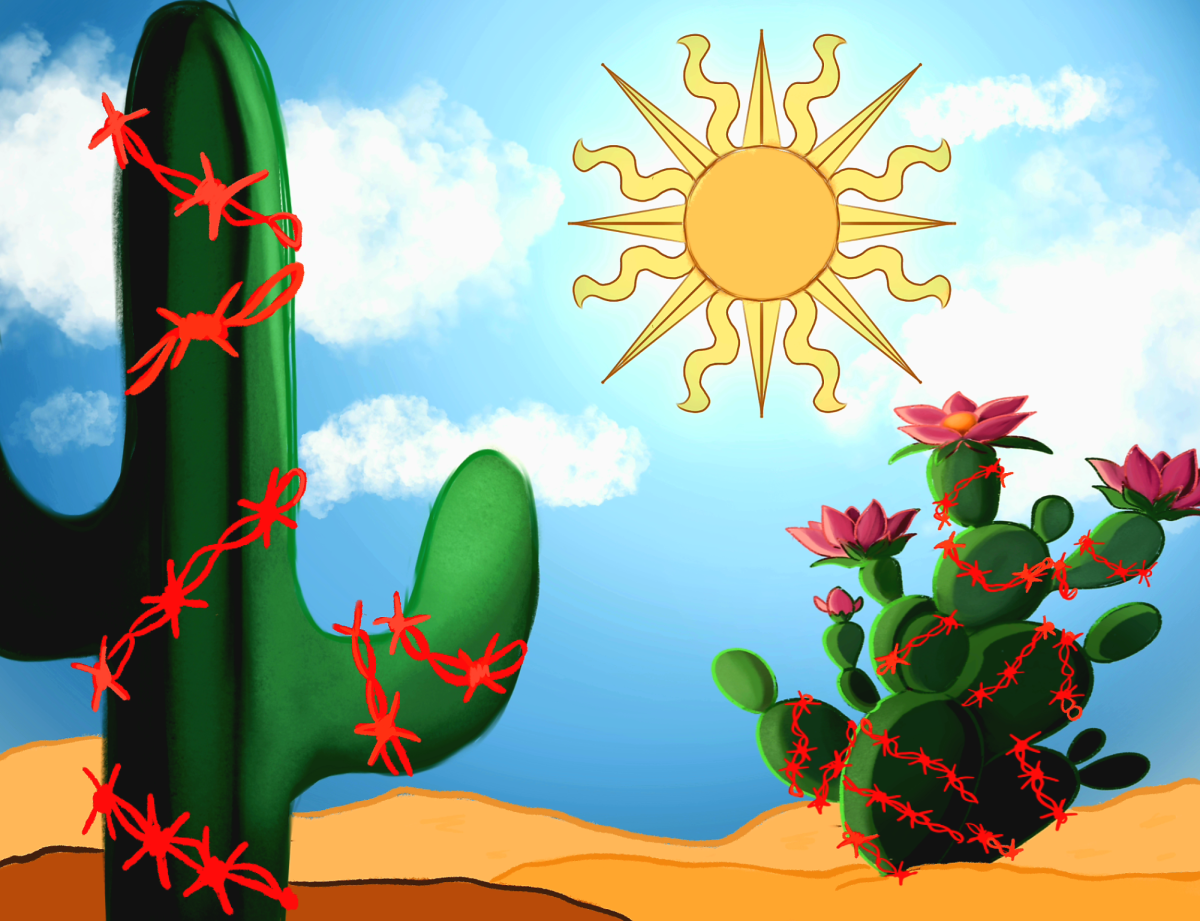

Sabo conducted the study, titled “Everyday Violence, Structural Racism and Mistreatment at the U.S.–Mexico Border,” with other UA faculty. The study focused on the health of migrant farmworkers in the border regions, which also included a look at the militarization of the border with things like racial profiling and immigration-related violence. During the time the study was conducted, several policies concerning immigration were passed. These policies allowed local police forces to ask community members questions regarding their immigration status, Sabo said.

Sabo said that through the study they found that these policies, which are directed at undocumented people, “spillover” into the citizens and permanent residents of these border communities — many of which are of Mexican descent. The study, she said, focuses on the concept of “everyday violence” happening to these people “just because of what they look like.”

“That’s a really big issue because in that paper, you might have seen that there were several instances of verbal abuse, emotional abuse and even physical abuse that were occurring to people that were not at all in violation of a law,” Sabo said. “They were living their daily lives. They were working, they were going to school, they were going to the grocery store.”

No less than 30 percent of the participants in the study experienced “immigration-related mistreatment,” according to Sabo. The participants in the study were predominantly U.S. citizens and permanent residents of the country, and Sabo said that they had lived an average of 15 to 20 years in the U.S. prior to the study. This mistreatment included racial profiling, being pulled over or stopped at the border, being detained for hours and, in some cases, verbal or physical abuse, according to Sabo.

However, this ability to “stop and ask people questions based on the fact that they look like they might be immigrants” is actually written in the constitution in one of the amendments under the Fourth Amendment called border exceptions, according to Anna O’Leary, the department head of Mexican-American studies and an associate professor in the department.

These exceptions come into play a certain distance from the border, where for roving stops “officers may inquire into [people’s] residence status, either by asking a few questions or by checking papers … so long as the stops are not truly random” and officers have reasonable suspicion that “an automobile contains illegal aliens,” according to an online document about the Fourth Amendment by the United States Government Publishing Office.

“It’s an interesting point of fact that is quite disturbing, which is why when there’s lawsuits against Arizona or anybody for racial profiling;there’s little that anybody can do about it,” O’Leary said. “A high percentage [of those in border communities] are U.S. citizens with every right to conduct business and to live here and to work here, yet they are always subjected to detention because they look like they’re Mexican.”

When discrimination-related issues occur within this region — which O’Leary said is often called the deconstitutionalized region by immigrant rights groups — those who are discriminated against are often afraid to file a complaint about their treatment, according to Sabo.

“Most people said that they would not make a complaint out of fear that they would be deported, even though they’re citizens or permanent residents, or that somebody would come after their family or that they would lose property,” Sabo said. “So even though people have all of these rights, they’re still very, very fearful to push against the system that exists.”

In order to solve this problem, Sabo recommended increased transparency within the Border Patrol. She said that she listed several policy recommendations in a different study that she worked on with Alison Elizabeth Lee, titled “The Spillover of U.S. Immigration Policy on Citizens and Permanent Residents of Mexican Descent: How Internalizing ‘Illegality’ Impacts Public Health in the Borderlands” and published online in June 2015 on the PubMed Central website.

These policy suggestions include a “transparent, community-centered oversight system to document and monitor immigration-related victimization” and creating a plan for accountability for law enforcement “to systematically report and respond to community concerns of corruption and excessive use of force,” according to the study.

O’Leary, who has been a coordinator for community organizations involved in research concerning farm worker populations in Yuma, said that civic engagement could create changes in these border communities.

“Those who can mobilize politically should do so in defense of those who can’t defend themselves because they’re constantly being targeted or discriminated,” O’Leary said. “Elections have consequences, and those of us who care what our country looks like have to take steps to be civically engaged to improve the world so that it reflects our values.”

Follow Ava Garcia on Twitter.