After learning about migrants’ struggles, Jody Ipsen felt compelled to find a way for the community to honor and never forget those who have died crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. The Migrant Quilt Project was her response.

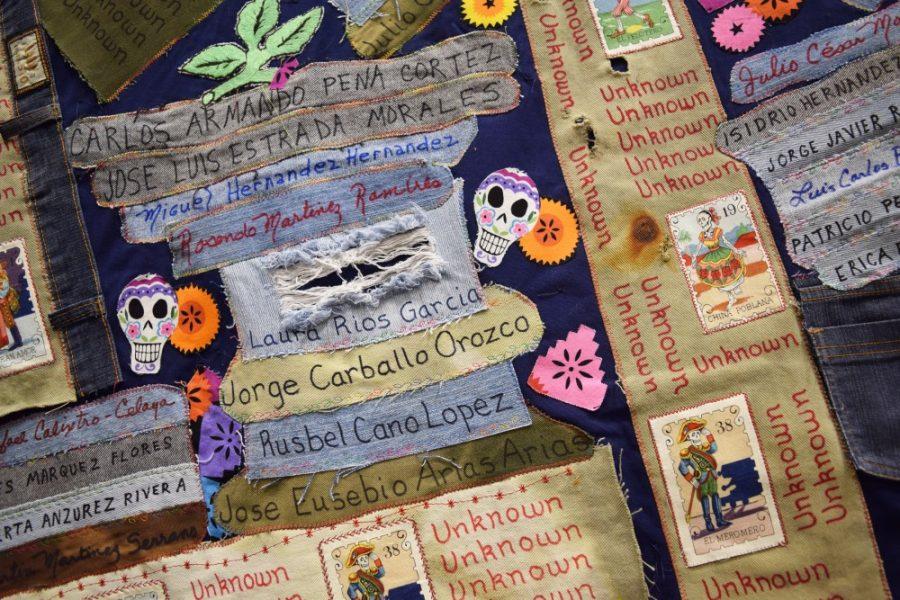

Volunteers with the project clean up sites throughout the desert along the U.S.-Mexico border where they find the possessions migrants have left behind while crossing. They take the clothes and create quilts embroidered with the names of the migrants to which they once belonged. When they can’t find the name, they simply embroider “desconocido”—”unknown”.

“It really spoke to me on a visceral level, like, ‘oh my God humanity is out there in the desert dying without food, water or medical care,’” Ipsen said.

When Ipsen was young, her mother would cross the border to take Ipsen and her brother to get braces in Nogales.

“We had this back-and-forth relationship with Mexico, and I grew up with a lot of Latinos and Hispanics and befriended them and went to quinceañeras,” Ipsen said.

Despite living in Tucson her entire life, Ipsen only started to hear of people dying in the desert while migrating to the U.S. in 2005.

RELATED: Column: U.S.-Mexico border sees fewer arrests, despite President Trump taking no action

The project stemmed from the non-profit organization Los Desconocidos, which Ipsen started in 2007. Ipsen’s mission is to remember the thousands of migrants who have succumbed to the dangers of the desert since 2000. She does this as a way to bring people’s attention to U.S. policies that lead many migrants to their deaths.

Sonia Arellano, a UA doctorate student studying rhetoric, composition and teaching English, is one of the volunteers with the Migrant Quilt Project. Her involvement with the project started when her dissertation director told her about the quilt showing at Tucson Meet Yourself in 2014.

Initially, Arellano only wanted to see the quilts. She thought to study other quilt projects but ended up just focusing on the work of the migrant-quilt making.

Many of the materials they recover are torn and stained with blood. Some migrants even leave children’s clothing behind.

“I wasn’t expecting to make a quilt myself,” Arellano said. “I couldn’t understand how a material product could affect U.S. immigration policy. I wasn’t expecting that to show the deeper, real issues that show our immigration policy.”

Between 1990 and 2012, the majority of identified undocumented immigrants—82 percent—were of Mexican origin. Guatemalan and Salvadoran immigrants composed 7 percent of undocumented immigrants, and 2 percent were Hondurans according to a 2013 Binational Migration Institute report at the UA.

The report suggests that the undocumented migrant death rate has increased in Southern Arizona, possibly doubling between 2009 and 2011.

While Arellano doesn’t think one quilt alone will make a difference, she believes the display of the collection of quilts will.

“Just like individuals may not make a huge impact, but collectively they do,” she said.

She thinks there’s a huge lack of awareness with the local population about the reality of the border. She’s always shocked when she encounters people who visit or are from Tucson who are unfamiliar with migrant issues.

Quilts serve as a material way to learn and interact with the narratives of migrant issues and their lives. Traditionally, quilting has reflected social justice issues dating back to slavery.

“It was just by happenstance that I wanted to do something with these clothes in the desert and it occurred to me to make quilts from the desert,” Ipsen said. “Historically they play a significant role in social justice issues as a medium for speaking to the larger issues on hand.”

Arellano’s mother was a seamstress, so she learned some techniques as a child. Arellano later earned a grant to take a quilt class but says she still feels new to quilting. So far, she has completed one small quilt and is working on another for the Migrant Quilt Project.

“It’s interesting because it’s not a traditional quilt in any way,” Arellano said.

The hardest part is the time and labor-intensive process it takes to piece together what is left from a person whose life ended in the desert.

“I never understood the amount of labor that goes into making a quilt, “ Arellano said. “The difficulty is immense. You’re working with blood-stained clothing or self-mended clothing. It’s emotionally exhausting and it’s physically difficult piecing that many things—it’s tough.”

The emotional labor was not something Arellano anticipated. Because she is a rhetorician, she carefully thinks about how to construct the quilt in order to send the message she wants.

Although her quilt will not count as part of her dissertation, she recognizes the research that goes into a quilt. One of her dissertation chapters talks about the act of quilting as a research method.

The focus of Arellano’s dissertation lies in analyzing the quilts to understand their rhetorical function, in this case, their intended message is to raise awareness about immigration policy and issues.

The greatest reaction Ipsen has seen has been from the people who see the quilts for the first time and are moved by the enormity of the quilts and number of names. Each year, approximately 170 to 175 names are on the quilt, according to Ipsen.

Through Ipsen’s years as an activist, the shift in consciousness for humanity and how fragile it is, especially to those disenfranchised, is what she has learned the most.

“I really feel consciously I have had a major shift in my perception of the border issues and of U.S. policy that has created this funneling of lives to really remote parts in the desert that people succumb to,” Ipsen said.

Follow Angela Martinez on Twitter.