Death Cab For Cutie’s newest and eighth studio album, Kintsugi, has its moments of greatness, but remains in the doorstep more often than not. The follow up to 2011’s Codes And Keys marks a couple of changes. It’s the first record since frontman Ben Gibbard divorced Zooey Deschanel, the well-loved actress that seemed such a good fit for him. However, Gibbard’s “500 Days of Summer” have been over for a while, since the singer has reportedly given his heart to someone else.

Naturally, Gibbard’s authenticity for teenage excitement visibly suffered from the discovery of the gloomy disappointment he encountered in adulthood.

“I still see you through the eyes of a child,” Gibbard sings in “You’ve Haunted Me All My Life,” a song playing with these motifs: “You’re the mistress that I can’t make my wife.”

Kintsugi also marks the first album in Death Cab’s 17-year, eight-album career that wasn’t produced by Gibbard’s partner-in-crime and band mate Chris Walla. Weird dynamics or sad understanding — whichever sentiments accompanied Walla’s statement that he would leave the band but finish Kintsugi first — are disguised behind a wall of professional producing by the first producer from outside the band’s confines, Rich Costey, a Hollywood guy who has worked with Muse and Glasvegas before.

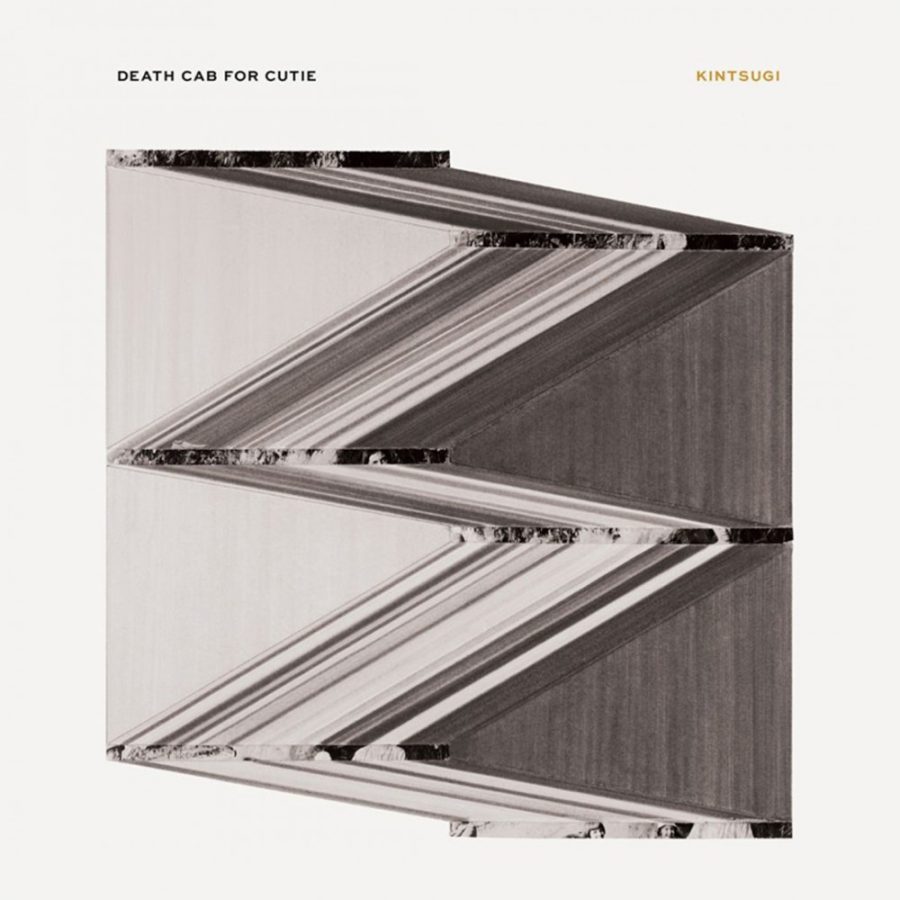

The album’s name toys with both these changes: Kintsugi derives from Japanese art, and is the act of putting broken pieces back together and building up something new and precious. However, a reinvention is not visible in Death Cab’s eighth album. In fact, Kintsugi gives more than enough “Death Cab-ness” to make fans happy. The album’s breakup theme cannot be misunderstood and feels just personal enough for the listener to want to give Gibbard a hug. It does not play out the kitsch too much, but it does not leave it unmentioned either.

The dynamic between Walla and Gibbard, most visible during the early stages of the band, seems lost for a while and finds its climax in this album. Where in the beginning, the fragility of Gibbard’s lyrics played right into the fragile production by Walla, the man that has bared his heart for the better part of his career is putting all his effort into catching the general sentiment, to make the general personal. Death Cab toes this line with clumsy grace.

That said, the album has its great moments. Pretty melodies openly admit their closeness to older Death Cab songs and provide steadiness between the album’s changing loud-quiet-big-small dynamics. “Everything’s a Ceiling” delivers unflattering 80s-synths, “El Dorado,” however, brings a moment of perfect Postal-Service-melancholia to the end of the album. With “The Ghosts Of Beverly Drive,” the band delivers a beautiful pop anthem in all its sing-and-clap perfection. Together with “No Room In Frame” and “Black Sun,” the album’s lead single, it opens the album on a strong tone.

Kintsugi is a much needed intermediate for Death Cab. Four years after its last record, Death Cab dips its feet into the novelty of losing a constant: Chris Walla. For the next album, Death Cab for Cutie will have to make do without him completely. Kintsugi is a worthy goodbye, and we’re ready to see what’s to come.

_______________

Follow Caren Badtke on Twitter.