Chemicals in Household items linked to early onset menopause

The average age of a mother at the time of giving birth to her first child was 21.4 in 1970. It is currently 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

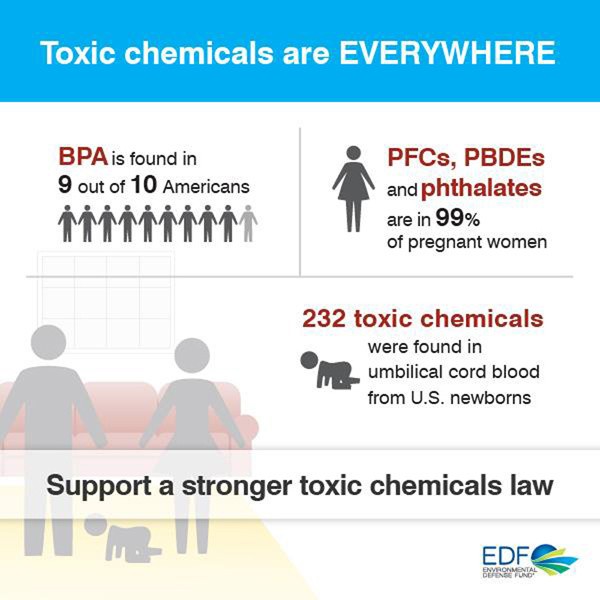

What no one expected is that the window of fertility is also shrinking because of common chemicals found in everyday products.

A new study from Washington University in St. Louis links earlier menopause with exposure to chemicals found in items around the house like cosmetics, prescription medicines and food packaging.

“These are just everyday exposures in the United States,” said Dr. Amber R. Cooper, co-author of the study and an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Washington University in St. Louis.

Understanding 45.6 million women

The study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, examined data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which the National Center for Health Statistics administered.

The researchers looked at the health data of more than 31,000 women, collected between 1999 and 2008. The team narrowed the sample down to 1,422 women who were over the age of 30, post-menopausal and had endocrine-disrupting chemicals in their blood. The sample of 1,442 women helps scientists understand the 45.6 million menopausal women in the United States.

The women in the study were then screened for 172 different chemicals. Of those, 15 negatively affected women’s reproductive health. Onset of menopause occurred from 1.9 to 3.8 years early in women who tested positive for these chemicals, even if they were not in extreme concentrations.

Early onset menopause is not only a problem for women’s reproductive health, but also for their bones. Menopause causes the ovaries to produce less estrogen, which signals the body to break down the bones. This condition, called osteoporosis, makes the bones weak and prone to fractures and often leads to chronic back pain.

Osteoporosis can also turn minor accidental falls into traumatic events.

Current phthalate experiments

The study linked one class of chemicals called phthalates to early onset menopause.

Phthalates are commonly added to plastics to increase flexibility and malleability. Manufacturers use phthalates in a huge variety of products, including medical tubing, prescription medicines, food packaging and personal care products such as perfume and shampoo, according to the National Institutes of Health.

“I truly hope [the study] doesn’t cause significant fear for women, but simply [creates] awareness and transparency,” Cooper said.

While phthalates are common in our homes, the human body can break them down and excrete them quickly, according to Zelieann R. Craig, an assistant professor at the UA studying the effect of phthalates on the ovary.

“It doesn’t matter how [well your body] disposes of [phthalates] because you are going to be exposed to it tomorrow,” Craig said.

She is trying to understand the molecular method in which phthalates can cause ovarian problems. To do this, Craig extracts follicles from mice ovaries and exposes them to phthalates with different inhibitors and growth factors. Follicles are the basic building block of the ovary. They secrete reproductive hormones and eventually release the egg.

Craig and her team also conduct animal studies where they expose mice to phthalates to confirm the results of their follicle studies.

“[In our experiments] we are using concentrations that are very close to what humans are exposed to every day,” Craig said.

Regulatory response to phthalates

Researchers have exposed cells to extremely high concentrations of phthalates, so it was difficult to make comparisons to the average person’s exposure, according to Craig.

It is hard for regulatory agencies, like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration, to create effective policies without useful data.

Some countries have laws regulating phthalate use. The European Union banned certain phthalates from children’s toys in 1999. The United States followed suit in 2008 when President George W. Bush signed into law the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act, which banned the same phthalates.

Both Craig and Cooper think we need more information to further regulate phthalates.

“I think that we’re still gathering the information and that EPA and FDA can’t do much until you can provide them sound data,” Craig said.

In addition, the FDA has recommended the pharmaceutical industry limit phthalate use in prescription drugs.

Cooper said physicians need to weigh the benefits and risks because phthalate-containing medication may be a patient’s only option to alleviate the symptoms of a serious disease.

Follow Patrick O’Connor on Twitter.