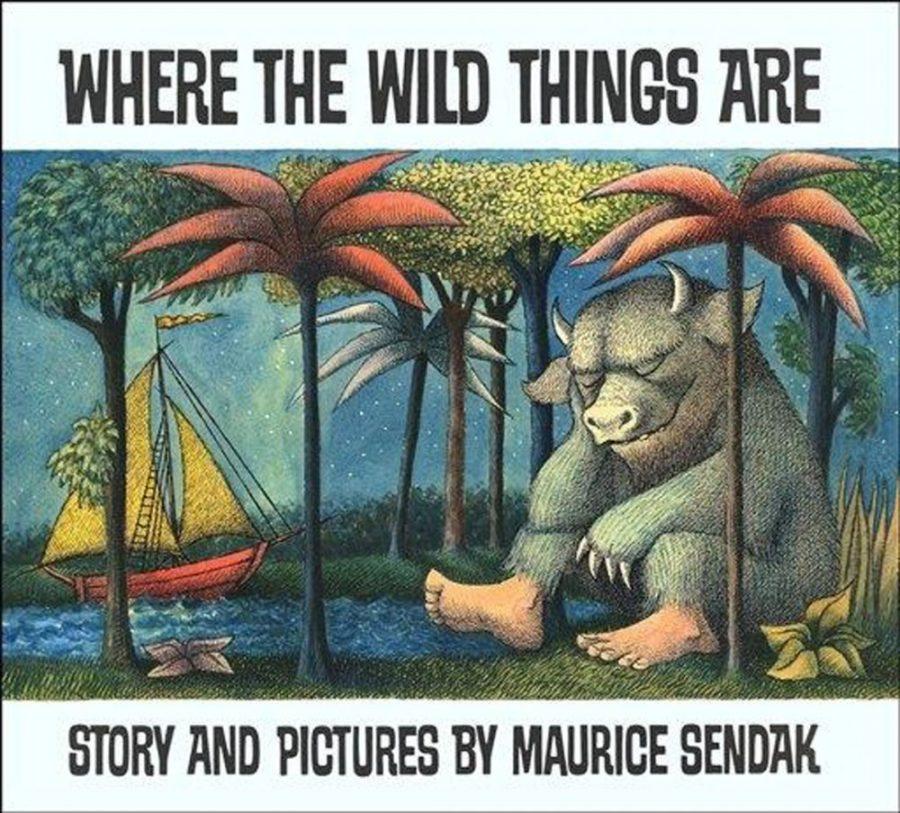

In 1963, Max was considered dangerous, disrespectful and accused of delving into witchcraft. Fearing these behaviors could be psychologically damaging to other children, complaints were filed. Fifty-two years later, Max’s creator, Maurice Sendak, won many awards for his book “Where the Wild Things Are.”

The picture book, with minimal text, is considered a brilliant depiction of a child’s perspective of resistance and a redemptive return to his mother from his fantasy escape. Sendaks’ work is known to have influenced other artists and is even a personal favorite of President Barack Obama.

The Tucson Festival of Books will bring Helaine Becker to the Sunday panel, “Banned Books: Why We Should Let Kids Read What They Want,” to discuss the importance of allowing children the freedom to choose their own reading material.

Having authored over 50 books for children and adults, Becker is slated to discuss why protecting children from literature might not be preparing them for real-life situations.

Children develop coping strategies as they read books about characters going through difficulties, giving children perspective, rather than being protected from literature’s difficult scenarios only to be unprepared when difficulty arises in their own lives, said Kathy Short, a UA professor, director of World of Words and co-chair for the children and teens author committee.

A common belief is that if banned books were put in elementary school libraries they would, essentially, be complicit in providing pornographic material to innocent children. This is not quite the case. Not every book that has been comprised in the increasing list of censored books to be kept far from children is on par with E.L. James’ “Fifty Shades of Grey” or would have made Henry Miller blush.

“Teachers and librarians are very aware of what is appropriate literature for children at different age levels, so they’re not going to be bringing in books that are inappropriate to the curriculum to what children of that age level and thinking can deal with,” Short said.

Technically, a book needs only one complaint to be considered for censorship; when it comes to anything regarding children, no complaint is taken lightly.

“While parents always have the right to say that their child as an individual should not read a particular book, they don’t have the right to say no one can read it,” Short said.

“Bridge to Terabithia” author Katherine Paterson, whose work has not been immune to banned books lists, will be at the Tucson Festival of Books along with other authors of books deemed in need of censoring.

Despite misconceptions that banned books all contain sexual content, it should be noted that banned literature has a history of including “Where’s Waldo?” and even the “Little House on the Prairie” series.

The American Library Association awards the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award every two years to children’s authors or illustrators who have made a significant impact in children’s literature. The award is highly prestigious and honors Ingalls’ contribution to American history and literature, despite her own famous literature reported to be banned for writing unflattering depictions of Native Americans. Despite the ban on Wilder’s “Little House on the Prairie” series, her canon is included in the Library of Congress and included on lists of literature that shaped America.

From the dictionary to “Little Red Riding Hood,” censored books have played an integral part in children’s lives, whether their judicious parents realize it or not.

Helaine Becker will discuss “Banned Books: Why We Should Let Kids Read What They Want” Sunday in the Education building in Room 333 at 2:30 p.m.

_______________

Follow Anna Mae Ludlum on Twitter.