For people with Type 2 diabetes, nerve damage in the legs can make walking a challenging and a potentially dangerous act.

To decrease these patients’ risk of falling, and to enhance their quality of life, UA researchers are turning to a technology more commonly associated with video games than clinical studies: virtual reality.

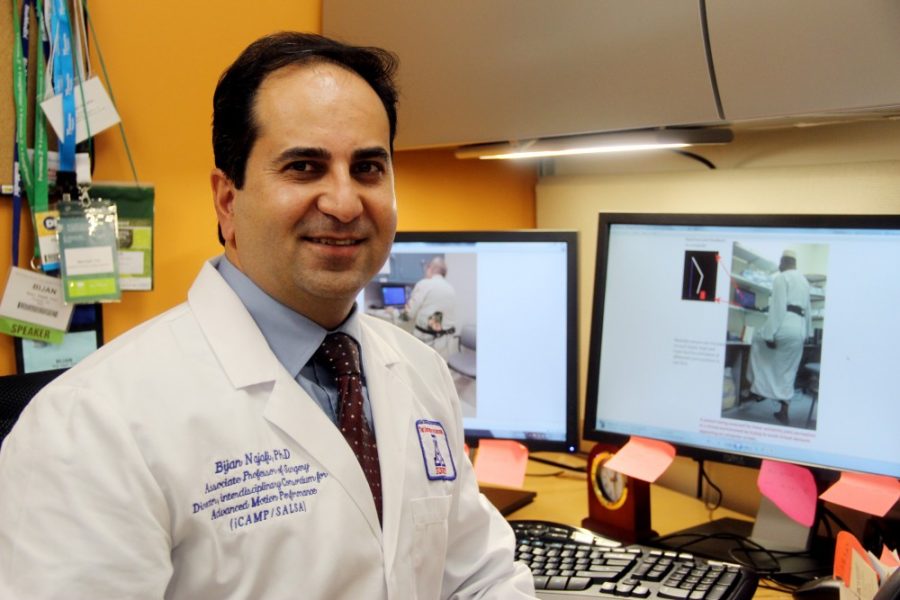

“Most of this [virtual reality technology] has been tailored just to create a game or entertainment for kids,” said Bijan Najafi, an associate professor in the UA Department of Surgery and leader of the series of clinical studies on the topic, as well as director of the Interdisciplinary Consortium on

Advanced Motion Performance. One of the studies was recently published in the Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. Najafi is currently leading another study that will be published soon, he said.

“Our question is, ‘What if we transform gaming to get some benefit for older adults … who have diabetes and a lack of sensation in the [feet]?’” Najafi said.

The goal of both studies is to use the virtual reality approach to improve the balance and mobility of patients while allowing them to engage in regular physical activity, which, according to Najafi, is crucial in managing diabetes.

“[Some patients] cannot easily navigate through their world; they cannot exercise,” Najafi said. “If we can find a way to provide them exercise that can help them enhance their balance, maybe we can help them to be more active.”

The system utilizes sensors attached to the hip and lower leg that track the movement of the subjects as they perform various tasks, such as raising one leg to avoid obstacles that scroll across a screen toward their virtual leg. If the patients don’t raise their leg high enough, or if they raise it too high, they are alerted by a sharp beeping sound.

Although the process resembles a simple video game, it is actually a powerful educational tool, said Jane Mohler, co-investigator of the current study. Mohler is also the associate director for the Arizona Center on Aging.

“It teaches them how to move in space, how to move more appropriately and it gives them feedback,” she said, adding that the instant feedback from the device allows patients to develop the “motor memory” needed to avoid obstacles in actual reality.

Patients in both studies showed significant improvements in balance and decreased “body sway” after the training sessions, Najafi said.

As for the future of virtual reality balance training, Najafi said that his team, as well as several others at the University of Arizona Medical Center, are working to expand the application of the technology to patients suffering from cancer and certain cognitive disorders.

However, computerized obstacles are just the first step.

The researchers’ ultimate goal is to prevent falls in the elderly diabetic population, said Dr. Nicholas Giovinco, the director of education for the Southern Arizona Limb Salvage Alliance. Giovinco is also collaborating with Najafi on multiple studies.

“One single fall can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and lead to major complications,” Giovinco said. “So if we can prevent the falls before they happen, then it’s totally worth it.”