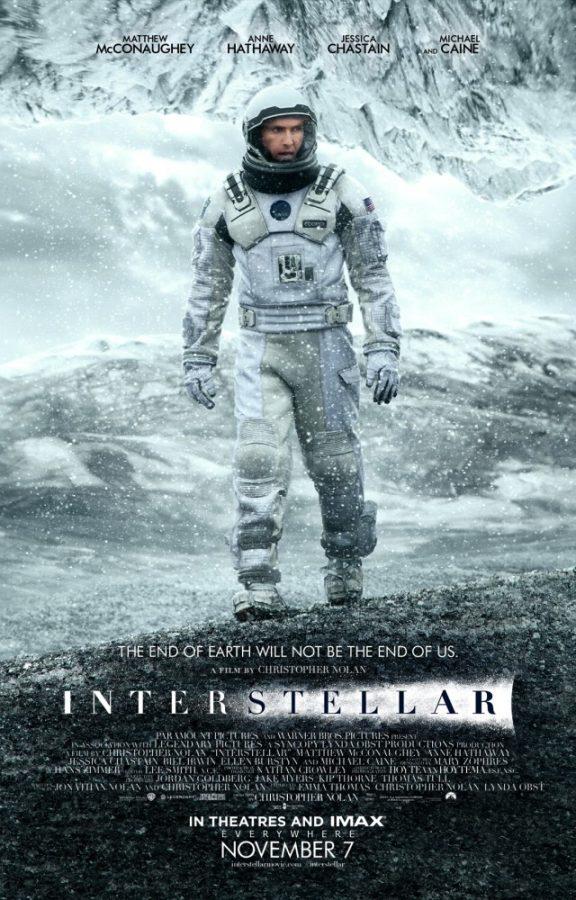

The latest from director Christopher Nolan — “The Dark Knight Trilogy,” “Inception” — has arrived, and this time he ascends to the stars. “Interstellar” is a colossal, galaxy-spanning event of a film whose monumental achievements, coupled with flaws, are starting to become as characteristic of a Nolan picture as its signature style.

The not-so-distant future presented in “Interstellar” seems vaguely prescient given the budget cuts to NASA and the disasters that have recently befallen shuttle launches. The mentality of, “Why bother about space when we’ve got so many problems to deal with here on Earth?” has been taken to its complete end. Dust — “the Blight” — suffocates the Earth and has destroyed every food source other than corn. Resources and technology go towards food production; there is no more military, and there is certainly no more NASA or space travel.

Cooper, played by a Matthew McConaughey that must bare his raw soul more than once, was a test pilot for NASA but now finds himself, like everyone else, unsatisfyingly tending the corn. His young daughter Murph, played exceptionally well by 13-year-old Mackenzie Foy, is the precocious light of his life since his wife passed away.

Through an unexplainable, anomalous event that Murph chalks up to a ghost behind the bookshelf, dust patterns on her floor lead Cooper to the last remnants of NASA, headed by Professor Brand, played by Nolan’s good luck charm Michael Caine, and his daughter Amelia, played by Anne Hathaway.

They have concluded that humans are damned to die if they stay on Earth. Like the Okies of the 1930s that were forced to traverse west to escape the Dust Bowl, humans must leave the only home they’ve ever known in order to survive.

The plan: Visit another galaxy via a wormhole that has opened up nearby in search of a planet that can be humanity’s fresh start. If there’s fuel left to get back to Earth, great; if not, the astronauts at least have fertilized embryos to repopulate humanity.

In a coincidence that is a little too convenient and compresses the first act unnaturally, it just so happens that this plan is happening tomorrow and Cooper, who’s just randomly shown up on their doorstep, is the exact person they’ve been looking for to man the “Endurance,” a spectacular, segmented spinning circle of a mother ship.

To save his daughter and not so much humanity, Cooper accepts. Cooper says goodbye to Murph, in a scene marked by the frustrated tears of a daughter who doesn’t understand why her father has to leave and the bitter tears of a father who has to abandon his daughter. It is this powerful bond, this intimate human emotion against the unendingly expansive canvas of space that makes “Interstellar” such a force.

That’s not to say that the canvas isn’t an absolute spectacle on the big screen, though. Filmed partially on 70-mm IMAX film, the visuals are of a magnitude that warrant, if not demand, the special treatment.

Dwarfing a nearby planet, a black hole holds light captive, its golden glow looking like the flowing sands of time. On an alien planet, a wave is so big that it’s mistaken for a mountain.

In Arizona, the only theater showing the 70-mm IMAX print is the Harkins Theatre at Arizona Mills, which is also the largest screen in the state. It’s worth the drive.

Having manipulated time on previous films like “Memento” and “Inception,” Nolan works on the largest scale here, employing concepts of relativity and space-time. The conceit first explored in “Inception,” which employed made-up rules about how time passed between the various dream layers, is magnified here, but with a respect to actual science. Relativity means that time doesn’t move the same way between different planets. It is a flooring realization when hours on an alien planet means decades on Earth.

Everything about this movie is large. However, the grandiose registers unnecessarily obtuse with some of the dialogue and ideas. Hathaway’s character delivers an impassioned monologue on the power of love, and it’s unsure whether she, and the film, believe that love is an actual, physical force. Indeed, it’s said that gravity, along with, yes, love, are the only two forces that transcend dimensions.

During production, Hathaway and Nolan were having trouble getting that line to register correctly. Hathaway was delivering it very powerfully and it wasn’t working, so Nolan suggested a more delicate approach. In the final version, there is absolutely nothing wrong with Hathaway’s delivery; it’s the line that’s broken.

The ending, which is not the only instance of influence from Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi classic, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” again dips into the metaphysical and the metaphorical to mixed results.

With every film he makes, Nolan doesn’t so much aim for the fences as he does aim to crush the ball out of the stratosphere. While “Interstellar” is decidedly imperfect, it is nevertheless a consummate film experience that should be beheld on the biggest screen possible.

Grade: B+

_______________

Follow Alex Guyton on Twitter.