Current Tucson Police Department Composite artists Jessica Romero and Krysta Kittoe did not join TPD knowing they would become composite artists creating sketches of crime suspects.

Kittoe initially joined TPD in the records department and underwent training to become a crime scene specialist as well. Romero, who graduated from the University of Arizona with a degree in studio art, initially joined TPD as a crime scene specialist documenting crime scenes and collecting forensic evidence.

“I didn’t really know too much about that [composite art],” Romero said. “I grew up in a small town where they didn’t have those resources available. They didn’t even have crime scene specialists. So, when I got into the job [crime scene specialist] and working for the department, I started seeing flyers for composite drawings and I thought they were really cool. That’d be awesome to be able to do that, especially having an art background.”

RELATED: Incarcerated artists find hope in creating an art exhibit

Both learned of the job opening through the retirement of crime scene specialist and composite artist Phyllis Gasparro, who graduated the UA in 1990. Unlike Kittoe and Romero, Gasparro began her involvement with TPD knowing what she wanted to do since college.

“A fellow student asked me, ‘So, what is it that you really want to do?’ I had the art background and a curiosity about investigations because I had always read murder mysteries when I was a kid and watched shows like that,” Gasparro said. “And so I said to the fellow student, ‘I would love to be a composite artist one day, but you probably have to be a cop first, and I don’t want to do that.”’

After Kittoe and Romero underwent around 160 hours of training each under Gasparro and others, they became certified composite artists.

However, the process of drawing a composite of a suspect was the most dependent on the victim, not the artist.

“After we start drawing, [the victim will] be there with us the whole time. They’ll look at the drawing and say, ‘OK, that looks good, but the nose was slightly higher than in the drawing.’ So, we’ll adjust the drawing accordingly,” Romero said. “It’s very much the victim or witness drawing, we’re just putting it on paper for them.”

RELATED: Forgery to thievery, a brief history of art crime at the UA Museum

According to Kittoe, the process of finding a witness or victim that could describe the suspect is not easy.

“Our detectives or officers always have to ask the three leading questions; one, ‘Would you recognize them if you saw them again;’ two, ‘Could you describe that person;’ and three, ‘Could you describe the details of their face,'” Kittoe said. “Because a lot of people will say yes to the first one, obviously they’ll say yes to the second one, but what people don’t seem to realize is that yeah I could describe let’s say my grandmother, but actually sitting down and verbally describing somebody even like that, that you love or that you see frequently, is much more difficult than people realize.”

Another common misconception about composite art, according to Kittoe, was that composite sketches could be used as strong evidence to convict a person.

“A lot of times [victims or witnesses] get in there, and they are nervous that the way they’re going to describe the person is going to be incorrect and the wrong person is going to get arrested and we would never arrest them [based on that],” Kittoe said.

After police find a witness or victim that they believe could describe the suspect in detail, the composite artists begin their work with an interview.

“We’ll start off with the interview. The interview is just allowing them to talk to us not necessarily of the crime but the [suspect’s] features they remember,” Romero said. “Even if it’s clothing, accessory items like glasses, hats, bandanas, anything like that, we’ll just let them talk until they’ve exhausted their recollection of the person.

Then the composite artists begin to get more specific features like eye or hair color.

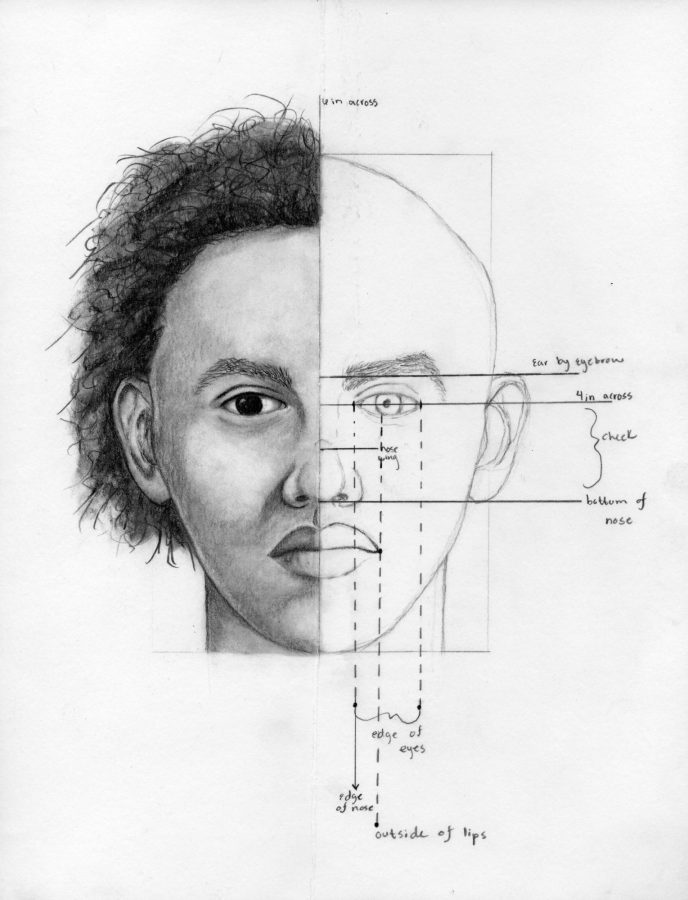

“And then, apart from that, we break down the face even more by having a section where we have reference material because someone’s recollection or idea of a certain shape may be different than somebody else’s,” Romero continued, “ It just gives a baseline so we know exactly what they are talking about.”

RELATED: OPINION: Criminalizing compassion

However, victims or witnesses of crimes could have a difficult time recounting a suspect due to trauma.

“The worst part of it was the emotional part,” Gasparro said. “On occasions when victims would become emotional or cry, that can affect my emotions also. I can not necessarily disconnect completely when that occurs.”

Despite the difficulties of the job, each composite artist discussed how there were positive outcomes.

“We’re able as composite artists to help the victim or the witness to help themselves because they are able to take a little bit of whatever power was taken from them in that situation back by them verbalizing, creating, helping us put this face down on paper,” Kittoe said.

In her own life, Kittoe’s career in composite drawing has reminded her not to judge someone’s character from their face and physical appearance.

“There’s been a couple times during drawings — where one [case] I had that was a pretty violent sexual assault where she said he had kind eyes, like he didn’t seem like a bad guy,” Kittoe said. “She was looking at his face when she was saying this. Obviously he ended up doing this horrific thing to her. People can put on a false face. More than their eyes, more than their face, I take people’s actions when I take my measure of someone is more based on actions as opposed to anything physical that they have or do.”

Follow Ella McCarville on Twitter