“Should English be the official language of the United States?” Max, a volunteer for a booth at the International Mother Languages event on the University of Arizona campus, asked me recxently. I answered no, based on logic. From the experience, though, I learned how much more conviction that ‘no’ has when it is based on people. When making political judgments, we should all act on the cliché and, “step into another person’s shoes.”

My task at the tent was simple; I had to fill out an application for school. Max handed me the paper, and I scanned through it. I smiled in disbelief. The application was in the Tohono O’odham language. There were dozens of black lines preceded by words I couldn’t understand. At first, it seemed like it wouldn’t be too difficult. I had filled out applications just like this numerous times in my life, and I could guess where certain information was supposed to go.

Like at the top — I knew that’s where my name went. But I realized I still didn’t know what to do. The first blank said “M-ce:gik.” Did that mean a first or last name? Or the whole thing?

I looked up at the volunteer. He smiled at me and began speaking in Tohono O’odham. He sounded like he was trying to help me, but it didn’t get me far. At the end of his sentence, he pointed to himself and said “Max.” Thank goodness I knew his name, or I would have just thought he was making more gestures. If his name wasn’t familiar to me, I still might not know whether it was a first name, or last name, or something completely different.

We made it all the way through the application. I figured out how to put in my birthday, my phone number and even my address with the help of index cards with little cartoons on them. I felt fulfilled for the moment. The experience was a fun one.

That was the closest I had ever come to being unable to complete a task because of a language barrier (how many Arizonans feel on a regular basis). But even this was so far from reality. Most people do not have a kind volunteer equipped with notecards to help them through paperwork. Some do not even know about the resources they miss out on.

Spanish is widely spoken in Pima County. At least 63,000 Spanish speakers here speak English at a level lower than “very well.” For that reason, many organizations, including the Community Food Bank, try to provide the same information in Spanish and English. Yet, when I volunteer, I am often surprised at how little Spanish speakers know about programs that will greatly help their families. Information is still less accessible to them than it is to English speakers.

For languages less prevalent than Spanish, inaccessibility becomes even more of a problem. In Arizona, it is estimated that there are about 15,000 Tohono O’odham speakers. About 1,200 speak English “not at all” or “not very well,” and about 6.5 percent of these 1,200 are children.

United States law tries to be inclusive of people who speak native languages. The Voting Rights Act, for example, requires polling locations in some counties to provide interpreters for some Native languages. However, the inclusivity is far from guaranteed. The Pima County Superior Court provides interpreters for many African, Asian, European and Middle Eastern dialects, though no options seem to be present for speakers of native languages.

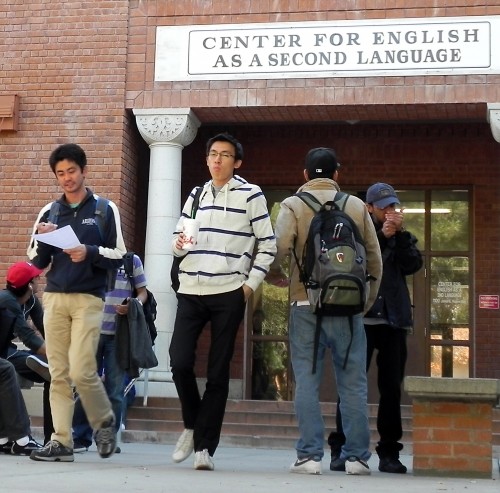

Our influence over law is often limited, but we can change the way we think about our language privilege and how we treat others in light of this knowledge. Many English speakers (me included) expect English to always be present while in the United States, and some of us don’t handle the situation well when it is not (I don’t hear the end of it when we run out of English pamphlets at the Community Food Bank.). Perhaps instead, we should remember that we are fortunate that most of the information available to us is understandable to us. Not everyone in Pima County can sign up for school, nor read this opinion piece, without assistance.

Let’s not forget why English isn’t our “official” language. Let’s not forget that just because we can understand, it does not mean that everyone can.