Listening to this two-disc retrospective of the most popular and controversial British band of the ’90s (apart, perhaps, from the Spice Girls) is a bittersweet experience. Few bands achieved so much so fast, and few burned it all up so fast. As the band asked in a 2000 song (sadly not included here), “”Where Did It All Go Wrong?””

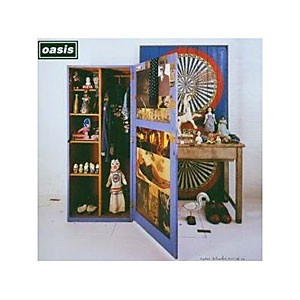

You won’t find much insight into that here, since this compilation is mostly about achievement. Sticking largely to material from the first two albums, 1994’s Definitely Maybe and 1995’s triumphant (What’s the Story) Morning Glory, Stop the Clocks makes a good case for Oasis as-when all the filler was stripped away-the best singles band of their day. In this context, even “”Wonderwall”” (their one U.S. hit, played ad nauseam in the late ’90s) sounds like a classic.

“”Some Might Say”” is a titanic rocker worthy of comparison with The Who, and the magnificent “”Don’t Look Back in Anger”” manages to combine the sound of Roxy Music with the surging spirit of Bruce Springsteen’s “”Born to Run.”” When Liam Gallagher cries, “”‘Cause I’ve been standing at the station/In need of education in the rain,”” it’s one of the most defiant and glorious moments in rock, even if the words seem like they were chosen entirely for their onomatopoeic value.

The compilation makes room for four of the band’s outstanding b-sides. The fiery “”Acquiesce”” stands with their best, and the brooding “”The Masterplan”” is close to a masterpiece.

At the time, it was hip to prefer the dim Kinks imitations of Blur or the watery prog-rock mewlings of Radiohead. It was hipper still to bluster that Oasis were mere shallow poseurs, unfit to be mentioned in the same breath as The Beatles, with whom they had blasphemously compared themselves, as if rock’n’roll had ever been about reverence for the past (did anyone object when The Beatles claimed to be bigger than Elvis?).

But songwriter Noel Gallagher had a melancholic, almost tragic temperament that was oft-obscured by the band’s brash reputation. “”Cigarettes and Alcohol,”” despite its cheerful riff (filched from T. Rex’s “”Bang a Gong””), is a despairing working-class anthem; “”Supersonic,”” their lanky, laconic first single, demands: “”You can have it all, but/How much do you want it?”” The world’s most arrogant and ambitious band seemed to realize that taking over the world wouldn’t amount to much in the end.