This August marks the 40th anniversary of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, one of the most culturally romanticized and idolized fixtures in recent American history — and everyone knows once anything celebrates a decennial anniversary it’s fair game to be labeled as trendy again.

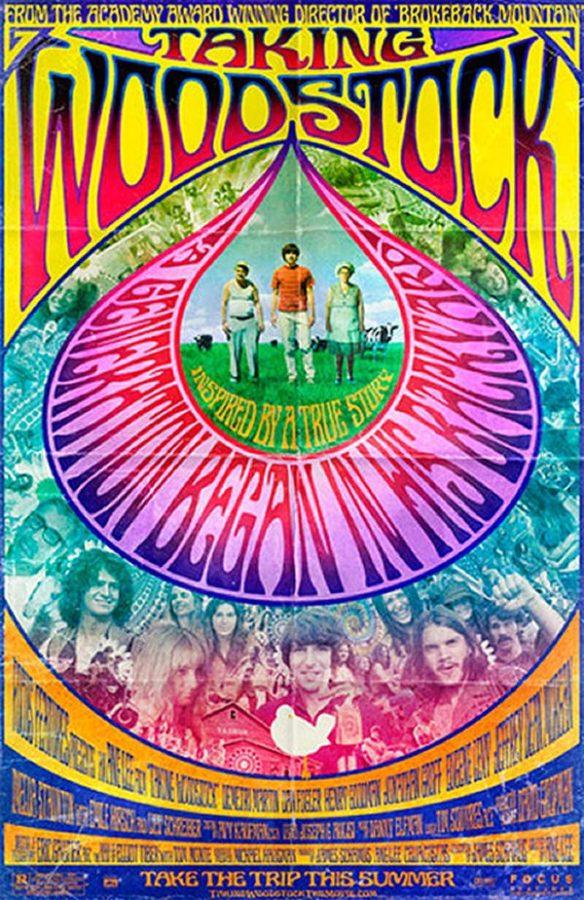

Seizing this opportunity to instigate some nostalgia (or residual acid flashbacks, as the case may be), hit-or-miss cultural critic Ang Lee presents his newest film, “”Taking Woodstock,”” a stereotyped pastiche of 1969 based on the book of the same name by Elliot Tiber, a man instrumental in the organization of the acclaimed concert.

It is important to distinguish right away that Lee’s “”Woodstock”” is not a sensory-shaking retrospective of this most influential and celebrated music festival. The director includes not a single scene of live music being performed, but rather focuses on the overall flavor and ideology behind the impromptu community of more than 500,000 flower children, rights activists and gurus of self-medication who converged on Yasgur’s Farm for three mud- and drug-soaked days in upstate New York.

If it’s the music of Woodstock you care most about (and, with a lineup featuring Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Creedence Clearwater Revival and The Who, why wouldn’t you?) then don’t waste your time with this oversimplified counterculture caricature. Rent the Martin Scorsese-edited 1970 documentary instead.

But if, like Ang Lee himself, you weren’t around New York to experience the surge of Woodstock at the time, and are more interested in a sweeping impression of the young, drug-addled festival-goer mindset, get ready to turn on, tune in and drop out.

“”Taking Woodstock”” tells the story of Elliot Tiber (born Elliot Teichberg and so referenced throughout the film), which is no doubt an interesting one despite allegations of fabrication.

Through the veil of a disappointingly drab performance by hipster funnyman Demetri Martin, Tiber’s life is recalled in exaggerated detail from his involvement in the Greenwich Village gay scene (yep, Demetri’s gay in this one — sorry ladies), to his role as Bethel Chamber of Commerce president and co-owner of the squalid El Monaco Motel, to his fortuitous poaching of the Woodstock Festival after it had been railroaded out of Wallkill, N.Y. by anti-hippie reactionaries.

Determined to build commerce for Bethel, Tiber directed Woodstock promoter Michael Lang (a vest-adorned flower child played expertly by Jonathan Groff who rides around on a white horse when not riding around in a helicopter) to the 600-acre farmland of Max Yasgur (a veritable chocolate milk alchemist played by Eugene Levy in one of his most refreshingly toned-down roles to date). Tiber wanted only to raise enough money from the event to prevent the foreclosure of the highway motel run by him and his cartoonishly Jewish parents, but what he got was a legitimate cultural revolution, coalesced from a countrywide smattering of love- and freedom-touting travelers.

The driving narrative of the film is the ill-omened organization of the festival and Tiber’s attempts to accommodate both his parents and the gargantuan exodus of hippies at the El Monaco Motel and surrounding farmland, but the emotional impetus is Tiber’s slow discovery of personal happiness during selfless attempts to save his parents’ livelihood. By dropping acid, engaging in orgies with strangers, and befriending flower-wearing cops and patrons alike, Tiber eventually finds that he is as much a part of the free-thinking Woodstock culture as he is the locally-maligned force behind it.

The aforementioned scenes of drug use, sexual experimentation and general hippie tomfoolery reflect the film’s greatest strength: the artful portrayal of the primary hippie dogma that powered Woodstock — the pervading sentiment of community and nonviolent liberation that made the festival such a significant cultural moment.

Where this film fails, however (aside from totally glossing over the music, without which there would have been no event) is its lazy writing and reliance on outmoded cultural stereotypes. Tiber’s parents are overt, almost offensive Jewish stereotypes, his Vietnam veteran buddy is a one-note war-addled wreck, his transvestite security chief (played by the muscle-y Liev Schreiber) is a shameless parody of him/herself, and the stuffy regime of Bethel elders are utterly detestable prudes.

Overall, “”Taking Woodstock”” is a panoramic snapshot of a landmark cultural happening taken by a man who was never there, and it shows. Lee succeeds at staying on point as far as the progressive ideology of the festival’s fraternal fan base is concerned, but comes close to compromising this utopian vision by peppering the cast with tired 1960s stereotypes and clichés. Give it a try if your ideal concert experience involves trippin’ in a Volkswagen bus and losing yourself in an ocean of fellow flower followers; otherwise, you’ll be duly disappointed when the bands never show up.