UA astronomers are using a state-of-the-art telescope to hunt for planets orbiting nearby stars.

Funded by NASA, the team is studying the interstellar dust around the stars as well as the dust that planets create as they orbit around stars. Currently, there are two such projects underway at the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) on Mt. Graham, near Safford, Ariz.

The Hunt for Observable Signatures of Terrestrial planetary Systems (HOSTS) will survey about 50 nearby stars and is slated to operate through 2017. The project will observe each star’s “zodiacal” disk, which is the cloud of dust that accumulates around a star due to collisions of nearby asteroids, among other things.

The LBTI Exozodi Exoplanet Common Hunt (LEECH) will also look at the zodiacal disks around other stars. LEECH will also seek to identify exoplanets which are planets that orbit stars other than our sun, namely gas-giants like Jupiter. The two projects will work simultaneously by using different science cameras on the LBT.

“The reason we want to detect such dust around extrasolar systems is because it can mask a planet inside,” said Denis Defrère, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Astronomy who is involved with both projects.

“One of the main goals of NASA over the next decades is to find an earth-like planet, and this dust is a show-stopper,” he said. “If the dust is too bright, we will not be able to detect earth-like planets inside the system.”

Which is where the cutting-edge technology of the LBT comes in handy.

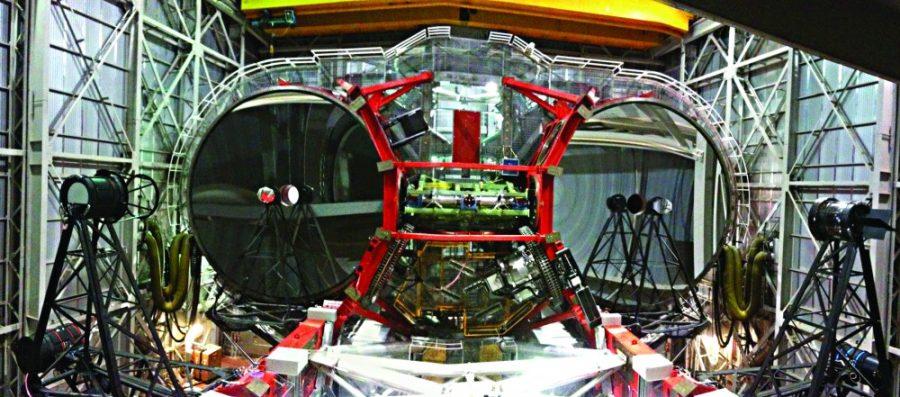

The telescope utilizes two 8.4 meter mirrors that were made at the Steward Observatory Mirror Lab on campus. The mirrors are positioned side-by-side like a pair of binoculars.

“The basic concept is, you spread the imaging portions of two telescopes and you get a much larger telescope,” said Tom McMahon, project manager for the Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer (LBTI), which is the instrument that combines the light from the two telescopes.

This technology allows astronomers working with LBTI to image the dust clouds with unprecedented resolution, he said.

“This is the only telescope in the world like this,” said Andy Skemer, postdoctoral researcher and principal investigator of LEECH. “Using LBTI, it turns this into the biggest telescope in the world.”

In addition to its resolving power, the LBTI is also capable of manipulating the incoming light in such a way that it cancels out much of the glare from the nearby star, making it possible to image very faint disks.

The information gathered from both HOSTS and LEECH will help astronomers to better understand not only the formation and composition of extrasolar systems, but also the composition of our own, Skemer said.

In addition to their short-term goals of observing exozodiacal disks, identifying gas-giants and studying the interaction between the two, the projects are also assessing the technology for application in a space-based telescope, McMahon said.

For now, the state-of-the-art LBT is the cheap alternative to a comparable space-based telescope, which would cost up to $5 billion dollars, Skemer added.

Although astronomers cannot yet image earth-like planets directly, the people at HOSTS and LEECH are gradually approaching that milestone, while furthering knowledge and understanding of the universe along the way.

“For me,” Defrère said, “It’s based on my curiosity and the will to learn and to discover new things.”