I still remember the first time I dealt cocaine. The sun hung low over Aburrá Valley, and I stared out over Medellín. My partner turned up the radio as we sat in our crappy pickup truck, waiting for the buyers to show.

These types of deals are like speed dates, you don’t know what to expect. You walk in, palms sweating, worried that the person you are about to meet is a complete weirdo. Hello, nice to meet you.

One bad date doesn’t mean much, but a bad relationship can get ugly. Breakups within drug cartels usually end with more bloodshed than tears. The nice thing is that if you are the hands and feet of a drug kingpin like Pablo Escobar, people tend to be on their best behavior.

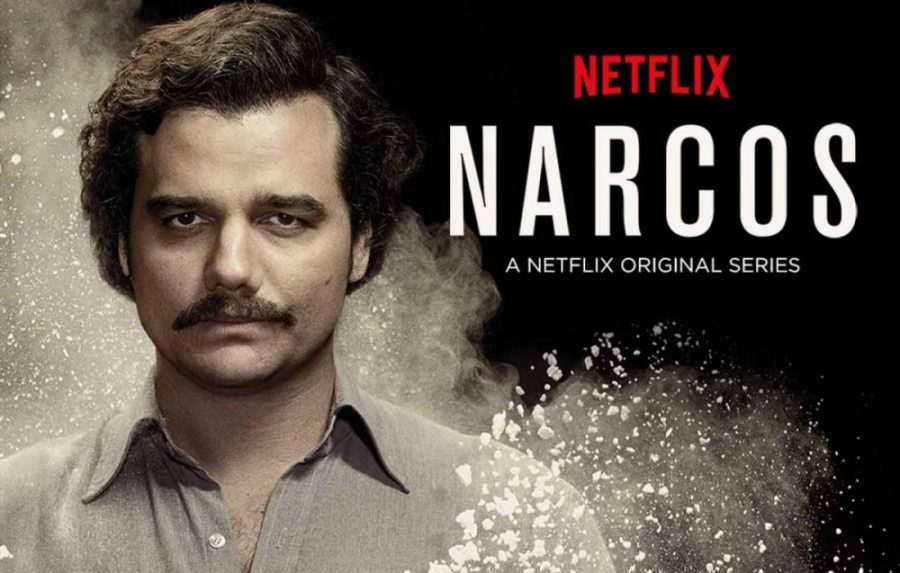

How much of this is true? Riddle me this: what are the odds of a white, American college kid getting his hands on a time machine and using it to sell drugs? On the other hand, how much does factual accuracy matter to any story? The practice of mixing together history and drama has been around forever, and has recently been popularized by the likes of “Straight Outta Compton,” true crime podcast sensation “Serial” and the HBO miniseries “The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst.” Now comes the tale of Pablo Escobar, Colombian cocaine kingpin credited with bringing blow to America. The many faces of Escobar are chronicled in Netflix’s newest (and best) original show: “Narcos.”

“Narcos” prefaces Escobar’s tale with its definition of magical realism as “what happens when a highly detailed, realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe,” a definition the show borrows from Winona State University professor and writer Matthew Strecher.

While the show recounts true events, certain characters, events and plots have been dramatized by this invasive ‘magic’. “Narcos” follows in the footsteps of other works that have been heavily invaded by this fact-and-fiction-blurring magic (e.g. the Coen brothers’ classic “Fargo”). By and large “Narcos” acts as a character study on the many identities of Pablo Escobar.

When someone mentions Escobar, the first identity that surfaces is that of a Colombian drug lord. A man whose cocaine empire at one point brought in over $60 million per day. A man who lost $2.1 billion per year because the vast amount of money in storage was eaten by rats. For the most part, “Narcos” follows Pablo’s ascension to Emperor of Cocaine. The conflict of the show comes from the battle for his identity.

Escobar’s decision to pursue one role over another drives the course of Colombian history. “Narcos” introduces Escobar well before his days of sitting on the cocaine throne. The first third of “Narcos” follows him as he listens to Drake’s anthem “Started From The Bottom” on repeat while he maneuvers his way to the top of the drug lord pecking order.

Here is Pablo, man of the people. He is not one of the aristocrats, born with a silver spoon in mouth. Pablo later admonishes an advisor, “I am not a rich person. I am a poor person with money.” The massive chip on his shoulder empowers Pablo as he creates an empire. The conflicting nature of Escobar’s identities catch up to him when he inevitably flies too close to the sun.

Escobar plays the family man one scene, yet cheats on his wife the next. A ruthless drug dealer one moment and a Colombian Robin Hood the next, Pablo’s world begins to crumble when he can no longer play both sides of a coin.

At the end of the “Started From The Bottom” phase of “Narcos,” Escobar sets his sights on no longer running Colombia from behind the scenes: he dreams of becoming president.

However, a drug dealer cannot play politician by day, no matter how much Escobar attempts to control everything. Escobar’s identities collide when his wife goes into labor after finding out about his infidelity. At the crossroads of family man and philanderer, drug dealer and politician, Pablo hears from his right-hand man and cousin Gustavo: “We are bandits, not politicians.”

Escobar believes down to his core that he can control the world with his endless supply of money. At one point Escobar paid millions of dollars for rare, exotic birds to be trained to sit in one tree all day, which is the kind of egotistical insanity only millionaires can afford.

In response to Gustavo’s ultimatum on being a bandit or a politician, Escobar takes hold of his newborn daughter and smiles as the newspapers capture the moment for his campaign.

“Narcos” is an excellent show for a myriad of reasons. Stylish to a fault, the show bleeds cool. The narrator, Drug Enforcement Administration Agent Steve Murphy, even wears a leather jacket as a universal sign that this dude, and by extension the show, is cool. Pedro Pascal, of Oberyn Martell (“Game of Thrones”) fame, is wonderful as Murphy’s rule-bending partner Javier Peña.

Greater than all of these is the entrancing study of one Pablo Escobar. Wagner Moura portrays Escobar with a gravitas that steals every scene, that underlies the battle for Escobar’s soul—his conflict between roles as drug lord, politician, husband, father, hero of the people, rich man, poor man, bandit, revolutionary, factual historical figure and fictional dramatic character.

Worth the Watch: YES

Follow Alex Furrier on Twitter.