Her glowing green phosphorous button, worn to alert passersby of her presence in the mandatory blackout of Nazi Germany, alerted the infamous Berlin serial killer, whom Adolf Hitler feared would shatter German morale, that his next victim was alone.

There were no passersby. Her potential cries would be unheard. Shining a light into her eyes, now accustomed to the dark, disoriented and temporarily blinded her. He then stabbed the unsuspecting woman in the back four times.

She lived to tell her tale of surviving the S-Bahn serial killer.

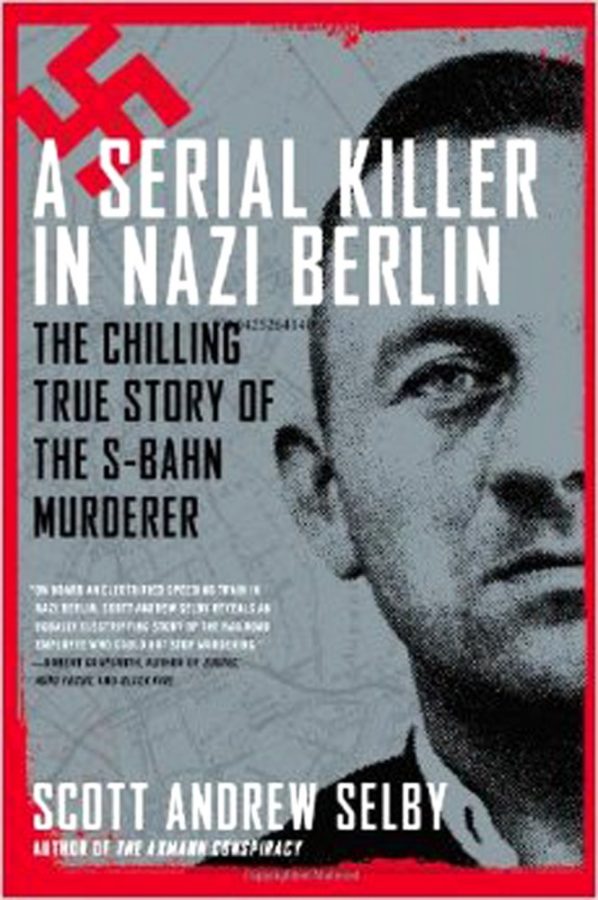

Scott Andrew Selby’s, “A Serial Killer in Nazi Berlin: The Chilling True Story of The S-Bahn Murderer,” brings Germany’s legendary serial killer to worldwide attention in his thorough account of Paul Ogorzow’s 1939-1941 path, from verbally abusing women to his insatiable need to sexually assault and kill them.

Ogorzow was seen as the quiet blue-collar neighbor — he cared for his wife and children and worked for Berlin’s commuter train, the S-Bahn. In reality, he beat his wife, kept mistresses and was a loyal sergeant in the Brownshirts, who delighted in frightening exhausted women walking home after midnight.

The reported crimes were closely guarded from the public by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi minister of propaganda. Fearing German soldiers would abandon the “Final Solution” to return home and protect their family, Goebbels squelched efforts to warn the women of Berlin.

Ogorzow’s quickly lost the original arousing effect of frightening women in the dark. His methods become more calculated, more frequent and more brazen. Ogorzow killed one woman in her kitchen as her children slept in the living room and one survivor was stabbed in the neck on the doorstep of her parents’ home.

When scaring and beating women no longer gave Ogorzow the same high, he found another means to experience his original feeling. During each sexual attack and through ridding the body from a moving train, he felt empowered, but — like a junky — the high rarely lasted long. He was constantly on the watch for petite women he could overpower.

Selby’s conservative descriptions of the attacks based on investigation reports and personal accounts convey the gravity of Ogorzow’s crimes without exploiting the victims further under the guise of “historical accuracy.” Unnecessarily graphic accounts of assault in historical nonfiction tend to be used for dramatic entertainment purposes when the true terror of another’s assault can’t be properly understood.

Selby removes the predilection to denounce the severity of assaults because the women attacked were the German equivalent to America’s “Rosie the Riveter.” The majority of the women he attacked worked in factories, so capable men could fight in the war.

It was a risky choice that paid off — to demand readers empathize for Nazi sympathizers — proving any attack of a person considered a lesser being can’t be justified.

The police were mostly Nazis searching for reasons to pin the crimes on possible Jewish citizens breaking their ghetto’s curfew. Each step to prove “the lesser humans” were responsible was unequivocally disproven.

Wilhelm Karl Lüdtke, police commissioner of the Serious Crimes Unit, was the moral detective investigating the homicides. Lüdtke is the unsung hero, having risked his life and career defending minorities, opposing Nazism and communism, and was eventually hired as a double agent for the CIA.

Ludtke’s persistence in finding the S-Bahn murderer simultaneously brought Nazi ideology into question as it became apparent that the crimes were committed by someone of the “superior race.”

The riveting cat-and-mouse game between Lüdtke and Ogorzow is truly spellbinding, shifting from moving trains to gardens and to Ogorzow’s interrogations. The epilogue wraps up the story of each character brought back to life by Selby.

Selby’s matter-of-fact writing is compelling, breezy and fact-heavy. He doesn’t linger on setting the scene. He thrusts the reader into the action, inserts forensic insight, provides closure when able and introduces Lüdtke, a hero ready for his overdue spotlight.

_______________

Follow Anna Mae Ludlum on Twitter.