On a warm mid-November morning at the Tohono O’odham Community College, Leslie Luna, Tohono O’odham Legislative Council Gu Vo’o District Representative, spoke about the attrition of his language.

“In 1988, about 90% of students were fluent O’odham speakers, but unfortunately, that number has flipped. Today, there are far more English speakers than O’odham speakers in our schools,” Luna said. “Those students [from 1988] are now in their 50s, and they are likely to be the last fluent speakers of their time.”

Luna’s voice sounds saddened in the vastness of the Sonoran Desert, but the ancient wilderness doesn’t seem too concerned. The morning sun casts a charm upon the land, with birds chirping and saguaro cacti standing tall. His words, however, reveal a truth that weighs heavy not only among his people but across the world.

In 2023, the Guardian said that every 40 days, a language dies.

These findings, shared by the Endangered Languages Catalog (ELCat), reveal that since 1960 the world has lost 28 language families.

“If we compare the extinction of a language to the extinction of an animal species, the death of a language family would equal the loss of a whole branch of the animal kingdom, for example all felines,” Karin Wiecha, the author of the ELCat, said.

This report further reveals that out of the roughly 7,000 languages spoken worldwide, 3,176 are endangered; this means that 46% of all living languages are at risk of disappearing.

Among these is the tongue of the Tohono O’odham, who have long inhabited the Sonoran Desert.

Tohono O’odham, a Tepiman language, is a part of the Uto-Aztecan family of southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico. The language has been declared endangered in Mexico and severely endangered in the United States by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

According to the Guardian’s 2011 UNESCO list of endangered languages, there were only 94 speakers of O’odham in Mexico. Thirteen years later, O’odham potter and basket weaver Reuben Naranjo, Ph.D., said that “there’s less than ten people who speak Tohono O’odham in Sonora.”

Similarly, Denise Ixchel Schafer, director of La Escuela Himdag Ki: Tohono O’odham Mexico and the daughter of José García Lewis, who is the leader of the O’odham in Mexico, said that there are very few people who can speak O’odham in Mexico.

There are only approximately 7,000 O’odham people in Mexico, yet very few can still speak their native language according to Verlon Jose, the Chairman of the Tohono O’odham Nation of Arizona.

As of April 2024, there were more than 36,000 Tribal members enrolled in the Tohono O’odham Nation according to the Chairman’s testimony. Out of these 36,000, slightly less than 10,000 reside on the Tohono O’odham Nation Reservation. The rest are spread out among the San Xavier Indian Reservation, Tucson, Phoenix, Gila Bend Reservation and Mexico.

According to the Endangered Languages Project, the total number of O’odham speakers is less than 14,000. Data from 2018 has shown that only 35% of adults (18+) and 12.5% of children (5-17) speak O’odham at home. This means that through time, O’odham has gradually been spoken less, mainly due to increased contact with English and Spanish in schools and beyond the reservation.

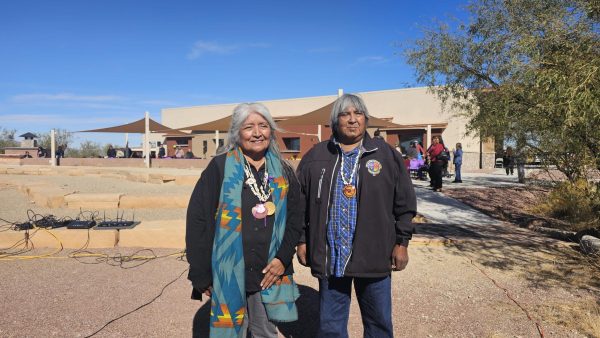

At the official opening celebration of the Tohono O’odham Language Center (O’odham Ňi’okĭ Ki:) on Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, directors Ronald Geronimo and Luna painted a painful picture of the situation of the language. O’odham is mostly spoken by older generations, with most parents who understand it but can’t speak it to their children, and children who almost no longer learn it as a mother tongue in the home.

O’odham weaver Elena Mendez, 51, didn’t learn O’odham as a child and couldn’t pass it on to her two daughters.

“My mother tried to teach us the language, but we as children thought it sounded funny because we only heard O’odham from her and a few other elders, so she eventually gave up, and now I regret that very much,” Mendez said.

O’odham Jamie Siquieros, 37, is a former student of Life Sciences at TOCC and is currently pursuing an associate’s degree in nursing at the University of Arizona. She grew up on the reservation with a mother who could understand O’odham, but couldn’t teach her.

“My mom was raised by her grandparents who came from a generation where they were punished for speaking O’odham at the boarding schools,” Siquieros said. “All that I learnt in O’odham was in my grandmother’s company.”

In her first year at the UA, Siquieros decided to study the language with Tohono O’odham professor Ofelia Zepeda because she wanted to preserve her linguistic roots and also because she dreams of practicing as a nurse on the Tohono O’odham reservation.

“It’s not only our language, but I think it’s also important for me to know some of it if I’ll be dealing with a lot of elders in the hospital,” Siquieros said.

O’odham Victor García, 34, is the owner of 3 Nations Market thrift stores in Ajo. He grew up in the village of Gu Oidak, south of Sells, Arizona.

“My grandma knew only how to speak O’odham, so I grew up listening to it, but then I began learning English in school,” García said. “So now, I can understand some O’odham, and speak little bits of it, but I’m really still learning how to speak it.”

García learns with O’odham elders.

“It’s a beautiful language that bears from the Earth,” García said.

García likes to greet people with the O’odham expression S-ke:g Si’alig, which means good morning.

The Tohono O’odham Nation encourages people like Siquieros and García to never give up learning.

“For those who are still learning, do not be discouraged, for everything you learn is a step forward in the preservation of our culture,” Luna said. “Please speak O’odham in your homes, even if just a few words, because it is in our daily conversations, around our dinner tables, in our prayers, that the language can continue to thrive.”

To fight against the loss of their ancestral language, the Tohono O’odham Nation has been making important efforts to revitalize and preserve it.

The O’odham tribal college offers an associate of arts in Tohono O’odham Studies, which includes O’odham language classes.

“The essence of TOCC and all the tribal colleges around the country is to revitalize and reclaim language and culture after over a century of federal assimilation policies that used education as a tool for cultural and physical violence, devastating native communities and ripping native families apart,” former TOCC president Paul M. Robertson said.

Until the 1970s, the O’odham language existed only in the spoken world. In an effort to document it, the first Tohono O’odham to English: English to Tohono O’odham dictionary was printed in 1983. In the same year, Ofelia Zepeda, who is now regents’ professor of Tohono O’odham and linguistics at the University of Arizona, published A Tohono O’odham Grammar, the only pedagogical textbook on the O’odham language ever written, which she uses to teach the only O’odham language classes offered at the UA.

Zepeda said she’s happy to have seen an increase in her number of students who are O’odham wishing to preserve their linguistic heritage.

“My O’odham students bring so much knowledge and experience from their families and communities,” Zepeda said.

Zepeda is also the chair of the Tohono O’odham Community College Board of Trustees and the co-founder of the American Indian Language Development Institute, which have both been involved in the establishment of the O’odham Ňi’okĭ Ki:, a 5,750-square foot building equipped with a large classroom, a recording studio, a kitchen, a library and offices on the TOCC’S-cuk Du’ag Maṣcamakuḍ.

The O’odham Ňi’okĭ Ki: also came to life in partnership with the Tohono O’odham Nation Legislative and Executive Councils, the Department of Education, the Baboquivari Unified School District and the Bureau of Indian Education Schools, among others. The building was made with the mission of cherishing, preserving, documenting and revitalizing the O’odham language by serving the entire O’odham community: the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Ak-Chin, Gila River, Salt River Pima Maricopa Indian Communities and the O’odham in Mexico.

“It serves as a place where speakers, learners [and] community members, can come together and breathe life into our language,” Luna said.

While the Tohono O’odham Community College and the University of Arizona offer language classes to adults, the O’odham Ňi’okĭ Ki wants to offer immersion programs in cooperation with schools that involve the elders of the Nation teaching the language to O’odham children.

O’odham Ňi’okĭ Ki director Geronimo realized the need for this Language Center when he first began teaching in the elementary schools on the reservation.

“I had always thought that everyone was growing up with O’odham, and learning English later in life, like me, until I started working at the primary schools, where I realized that the children were growing up with English,” Geronimo said. “The children are not learning O’odham, and if they’re growing without it, our language is going to die.”

Just like that, through the splendid and travailed journey of this O’odham teacher who dreamt of O’odham children carrying their language and Himdag (culture) into the future, the idea of the O’odham Ňi’okĭ Ki was conceived. And now, some years later, it is up and running strong.

In collaboration with the TOCC’s O’ohana Ki (the College Library), the center will store all materials related to the O’odham language and film, interpret elder oral stories and teach O’odham full-time to the children and the broader community to preserve the O’odham linguistic and cultural heritage.

“In the palm of our hands, we see our mother, father, grandmother, grandfather and so on down the generations. This reminds us that we are the continuation of our ancestors,” Luna said. “When we speak O’odham, we give voice to their spirit, keeping their memory alive and ensuring that their knowledge lives on.”