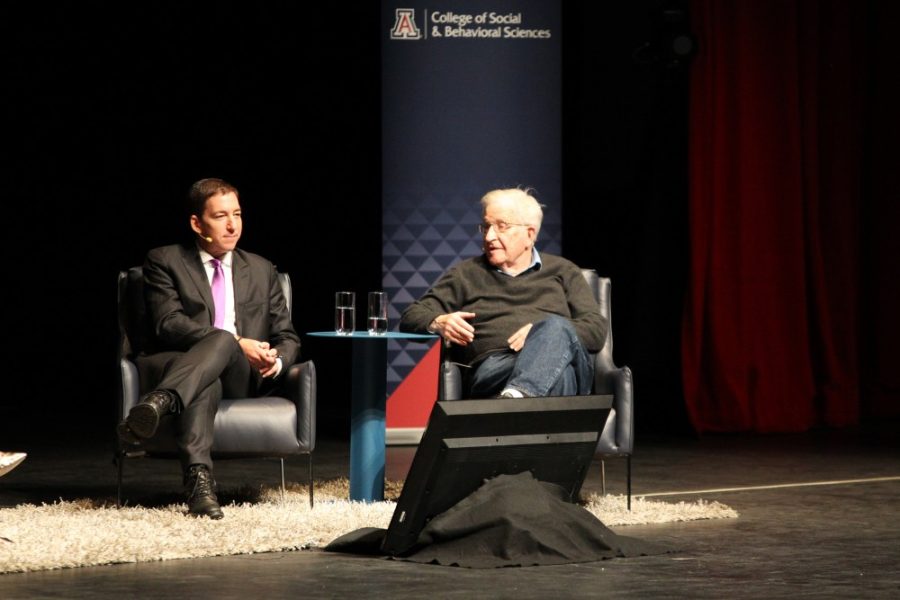

April 21 wrapped up one of the final lectures at the UA from esteemed linguistics professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and renowned intellectual, Noam Chomsky.

He cited a few of the ideas behind his latest book “Why Only Us: Language and Evolution,” which he co-wrote with Robert Berwick, professor of computational linguistics and computer science at MIT.

Theory and speculation on the evolution of language is an uncertain path for science. One theory suggests mouth movements may have initially signaled information about eating and evolved from there. With the history in mind, one might be tempted to say the book will be composed of a sort of academically written fluff.

The main ideas of “Why Only Us” are relatively straight forward: Can we study the evolution of language? What supporting evidence we can use to study this? What exactly are we studying?

Language has three critical components, according to Chomsky and Berwick.

The ways in which we create sound, the computational aspects and the meaning aspects.

In linguistics, there is a large emphasis on the phonological and conceptual aspects, mainly because a language’s phonologic structure is relatively easy to gather data on. Chomsky, however, has always emphasized the computational aspect.

“The most elementary property of our shared language capacity is that it enables us to construct and interpret a discrete infinity of hierarchically structured expressions: discrete because there are five-word sentences and six-word sentences, but no five-and-a-half-word sentences; infinite because there is no longest sentence,” Chomsky and Berwick wrote in the book.

It is this ability that may separate us from primates, according to some researchers. A famous experiment with a chimp named Nim Chimpsky showed chimpanzees lack the ability to properly interpret grammar or syntax, keeping them from constructing sentences in the same way humans do.

Chomsky and Berwick look at the possibility of there being any genetic basis for this in chapter one of “Why Only Us.”

One candidate is a gene named FoxP2, which boosts the ability to shift declarative memory, or memory of which we are conscious, to procedural memory, or the part of long-term memory that is responsible for motor skills.

In the final chapters of the book, Berwick and Chomsky map key links between the temporal and frontal lobes of the adult human brain and compare them to links in chimpanzees and human babies.

It appeared that a ring forming between two parts of the brain, the arcuate fasciculus and a fiber called STS, almost connects in the Macaque monkey. In humans, however, the ring is complete.

Chomsky and Berwick theorize this slight difference may have larger implications. They also theorize it may be an evolutionary abnormality, more or less, caused by random evolution rather than gradual adaption.

All of this combined is why our brains are different and more complex compared to our evolutionary relatives, according to Chomsky and Berwick.

If you are a fan of Chomsky or curious about the human brain, pick up this latest publication in science.

Follow Alexandria Farrar on Twitter.