Juno, a NASA probe launched in 2011 from Cape Canaveral and now in orbit around Jupiter, completed a flyby — its closest yet — of the gas giant’s Great Red Spot on Monday. The spacecraft recorded close-up photos of Jupiter’s well-known high-pressure zone and captured data which will better our understanding of the planet and by extension the solar system.

Juno entered Jupiter’s orbit on July 5, 2016, and has been gathering data ever since. The probe was first proposed to NASA by a team of investigators lead by Southwest Research Institute physicist Scott Bolton. The group had to design a resilient probe that could survive millions of miles away from the Earth.

“The biggest challenge was making sure the spacecraft had reliable power,” said William Hubbard, UA Lunar and Planetary Laboratory professor emeritus and Juno co-investigator. “When you send spacecraft all the way out to Jupiter, the sunlight is not very strong.”

RELATED: Headlines from space: Possible planet in the Kuiper belt?

To counter this Juno was given massive solar panels — which additionally provide stability for the craft, essential for the precise gravity and magnetism measurements it needs to take. It was also designed to run all its major features with minimal energy consumption.

“The actual power output is the equivalent of several 100-watt light bulbs,” Hubbard said.

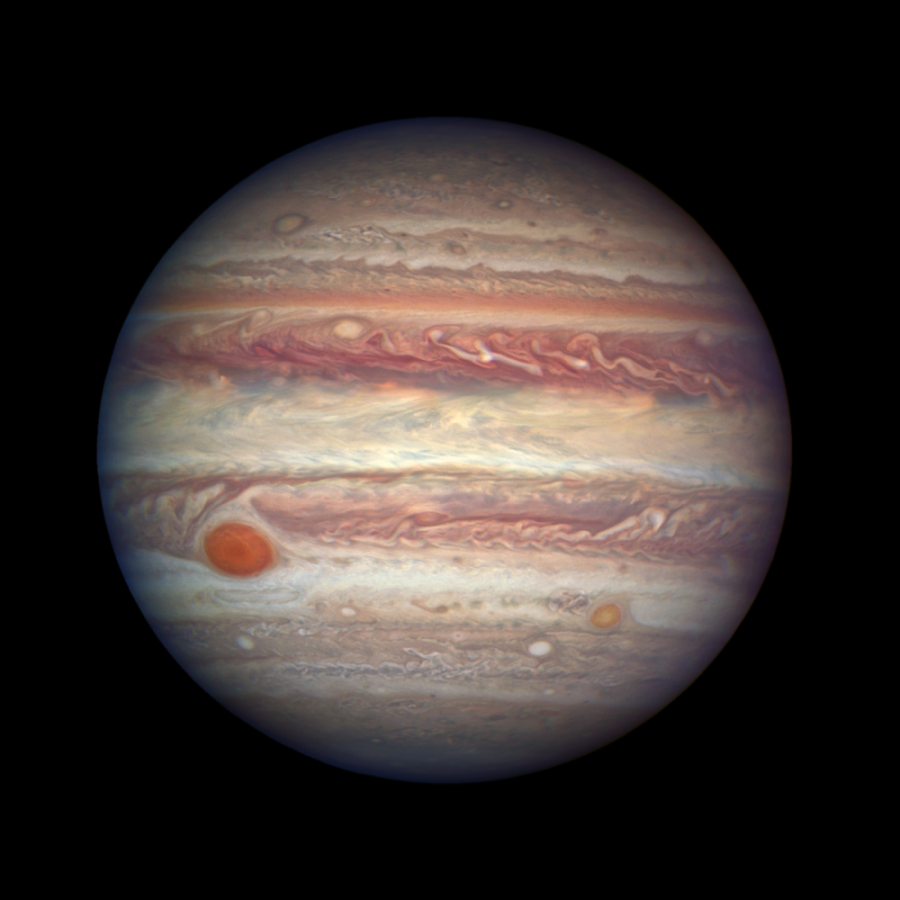

What made this flyby special was the Great Red Spot’s perfect alignment with the probe. Drifting in longitude, the massive storm has been a feature on Jupiter for several centuries and has been observed ever since people began peering through telescopes at the planet.

“Records show that the storm is a high-pressure region, unlike a conventional hurricane which is a low-pressure region,” Hubbard said.

The GRS rotates counterclockwise, and its color has been observed to occasionally change hues. Observations have indicated that it is shrinking. Records from the 20th century show it was more elliptical in shape, but the long-axis has been shortening, making the spot more circular.

“We’re quite pleased, as the GRS was in the right place at the right time, and we got high resolution images which will let us look at the structure of the storm,” said Planetary Science Institute senior scientist Candice Hansen, JunoCam designer and Juno co-investigator.

Since the most uncharted areas of Jupiter are around the poles, the team put Juno in an orbit around them. “We picked a width of our field of view as 58 degrees, so we could cover the whole polar region in one image,” Hansen said.

One issue with photography is that Juno is constantly spinning, which would normally make pictures blurry and useless. To counter this, a detector was added that could sense and move the camera to match the rate of spin, providing clear photos that have revealed previously undetected features.

RELATED: UA researchers building greenhouses for space

This flyby, also called a perijove, was the seventh to occur since Juno reached Jupiter. The probe will continue to make these flybys until approximately 2021.

“The main challenge was Juno was out of contact with the Earth because of how [the probe] was oriented,” Hansen said. “So all of our data had to fit with the on-board memory storage, which was challenging because we wanted to take lots of pictures.”

The camera with which Juno took these pictures was an add-on. “We wanted to have a camera, but because it wasn’t required for the science, we said, ‘let’s make it an outreach camera,’” Hansen said.

“The main challenge with this flyby was the radiation exposure. Every time Juno comes in close to Jupiter it gets exposed to harmful radiation,” he added. The radiation builds up over time, but Hubbard confirmed everything is working fine so far.

Follow William Rockwell on Twitter.