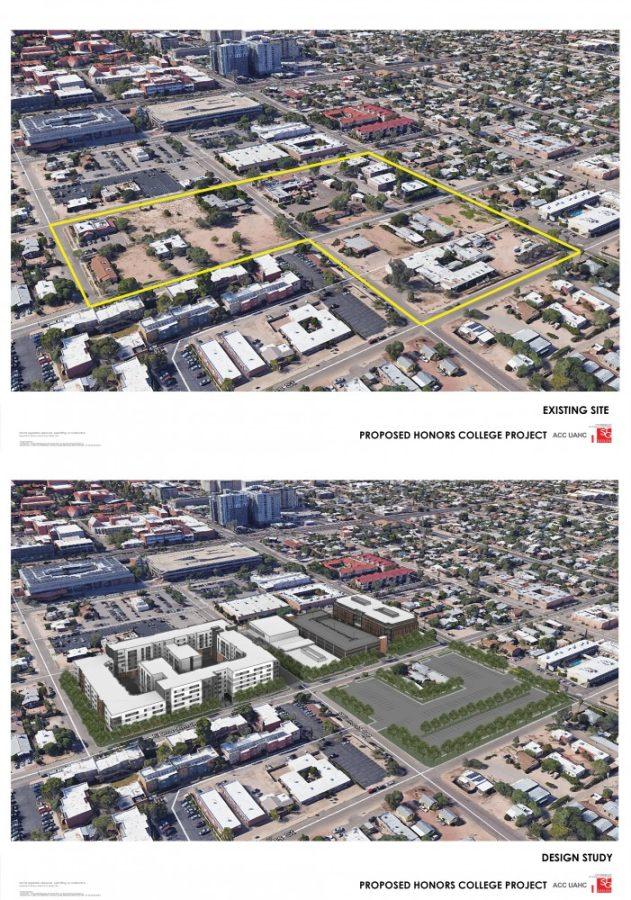

Three homes in the middle of the 1000 block on Drachman Street, between Park and Fremont avenues, were at the center of discussion during the third community meeting April 10, which concerned the development of UA’s new honors complex.

John and Jenny Sadlouskos, residents of one of the homes, sat in the front row as talk of their imminent plight surrounded them, much as the future parking lot American Campus Communities plans to build would surround their home.

But they’re not angry.

“You can’t stop progress,” John Sadlouskos, 85, said. “We hate to move, but we don’t want to live next to the parking lot.”

The Sadlouskoses have lived on the property for 65 years, but feel the representatives from ACC are taking their concerns into consideration.

Comments during the meeting indicate that other community members don’t feel the same.

The topic of discussion for the meeting was to collect suggestions from the community about design implementations to address their concerns, said UA Assistant Vice President for Planning Design and Construction Peter Dourlein.

Community members suggested everything from low-light lamps in the parking lot to moving part of the new 1,000-bed facility underground—an implementation Dourlein said would increase costs by three to four times the current amount.

RELATED: New Honors College village under debate

However, tones on each side became tense as community members began to question the process by which the ACC is attempting to develop the property.

“The meeting was a predictable food fight,” said Ward 6 Council Member Steve Kozachik. “Predictable because the way the university is going about this project, I think from the standpoint of public relations, from the standpoint of building community trust and credibility, the thing’s a train wreck.”

Amidst assurances that the university and ACC will do every they can to be good neighbors, Grace Rich, the North University Neighborhood Association president who lives on the east side of the complex’s proposed site, said the development would “basically ruin [her] life.”

“My question is—like the question of a lot of people—has this been planned and a done deal for a long time?” she said. “Are they gonna do this and just have meetings with the neighbors to say they’re having meetings with the neighbors, but actually we would not have any impact on having this project stopped?”

Rich would rather see the project halted altogether, and have resident homes built to strengthen the neighborhood. Ninety percent of the homes in the neighborhood are currently rented by students, she said.

If ACC were to develop the property without the university’s involvement, they’d have to adhere to the city’s medium residential zoning code, which limits building height to two stories. The university’s educational directive provides greater leeway.

Partnering with the university allows both parties to bypass that requirement and move ahead with the proposed four-to-six-story complex, which would include a residence hall, recreation center, dining and office space.

The university has the option to go through the regular channels of rezoning instead of working through the formal process, said Kozachik, who is also an associate director of athletics for facilities and capital projects at UA.

“Granted a rezoning would require some concessions … but pretty sure they’d get a rezoning,” Dourlein said. “There would be a development there of a greater density than what’s there now.”

Many of the meeting’s attendees were from outside the North University and Feldman’s neighborhoods surrounding the site, due to concerns about the precedent set by the development of the honors complex and the university’s public-private partnership with ACC.

RELATED: New Hub student housing will impact local businesses

“This is a concern to any neighborhood that’s surrounding campus,” Kozachik said. “That whenever the university feels like it, they’re gonna put together a memorandum of understanding with a private developer and just bypass the public process.”

Dourlein said that having the project adhere to city zoning requirements could set a different precedent.

“That would basically say that all state land in Arizona should go through city zoning processes,” he said. “That’s just not the way it works.”

Dourlein said the city’s zoning rules may not be anymore beneficial than the university’s.

“We try to build in a way that is similar to the city’s zoning,” he said. “It’s similar densities and we try to step-down a little bit as we get to neighbors.”

Additionally, neither the university nor ACC will have to pay taxes on the property under their partnership—a concern of Kozachik’s, as a half-cent sales tax increase is set to be voted on in May.

One of the meeting’s attendees called the university’s partnership with ACC a “shell game,” in reference to bypassing zoning requirements and tax obligations.

“I have some questions as to the legality of the whole thing,” Kozachik said. “If this model is allowed to move forward … then this could happen anywhere in the community.”

Kozachik currently has the development process under review by the city’s attorney.

Diana Lett, the preservation committee chair for the Feldman’s Neighborhood Association, threatened legal action against ACC.

“The problem is how it’s being done and where it’s being done,” she said. “An honors college, in and of itself, is not a bad idea, but the way this is being done, it’s deliberately structured to circumvent City of Tucson zoning and the planning process the university usually engages in when it builds something on its borders.”

According to Dourlein, the city’s rezoning process doesn’t guarantee the community’s concerns would be met, and could actually open up the possibility of higher density structures being built, such as the student-housing towers just south of the proposed honors complex site.

“To say ‘circumvent’ like that’s the whole intent—that’s not accurate,” he said. “We have our own standards and our own requirements and part of that is the community participation.”

Due to the legal threats, ACC representatives said they could not comment on the meeting’s discussion nor the development of the project.

Dourlein said design elements beyond the details of the development, such as an inner-courtyard to decrease noise pollution from students and an irrigation system that keeps 95 percent of water onsite to achieve Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification, are being implemented to make the complex as neighborhood friendly as possible.

“Comments that I made and that other people made pertaining to design issues may—may—be taken into account,” Lett said. “Maybe they’ll pay attention to some of that.”

Dourlein said the derailed topic of the meeting highlights the need to continue discussions with community members and hopefully find a compromise for continued development.

Follow Nick Meyers on Twitter.