UA researchers are using the side effects of a pain reliever, which raises body temperature to prevent anesthesia-induced hypothermia in the operating room.

“Currently there is not a single drug like this that can reverse the anesthesia-induced body temperature drop … so this would be a first in class,” said Dr. Amol Patwardhan, a practicing anesthesiologist and UA assistant professor of pharmacology and anesthesiology.

The proposed solution to preventing body temperature drop caused by anesthesia in patients is known as TRPV1.

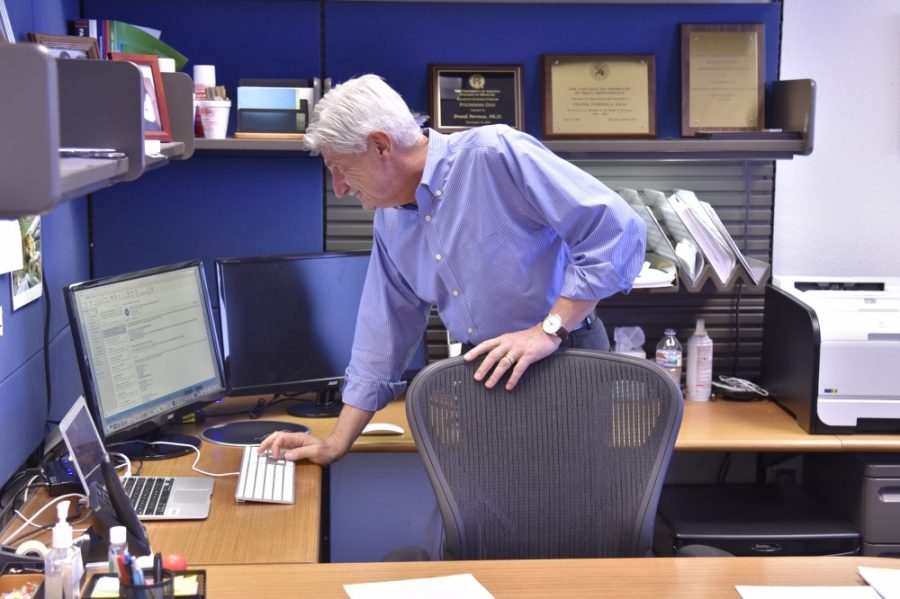

TRPV1 is a receptor that produces a sensation of heat when it is activated by outside stimuli, said Frank Porreca, a professor of anesthesiology and pharmacology, a pharmacology associate department head and Patwardhan’s research partner on the project.

TRPV1 was first discovered as a pain receptor and attracted the attention of pharmaceutical companies hoping to develop it as a potential analgesic or pain reliever, Patwardhan said.

However, the development of the drug was soon halted when it was discovered to produce fever-like symptoms in patients.

RELATED: UA professor honored for achievement in pain management

The TRPV1 channel is activated whenever it encounters stimuli in the environment that could be potentially dangerous, specifically in regards to heat, Porreca said.

Imagine if you were to bite into a jalapeño or take a sip of hot coffee, Porreca explained. The sensation of heat and subsequent pain comes from the activation of the TRPV1 channel.

“Companies thought, ‘Well, heat produces pain, if we block that channel we can make a drug that produces analgesia or pain relief, so we can use it for [a] therapeutic purpose’,” Porreca said.

Unfortunately, the drug yielded unexpected results during clinical trials.

The fever-inducing side effects of the TRPV1 drug made it too dangerous to be used as a pain reliever. But Patwardhan saw this as a potential solution to a serious problem facing anesthesiologists across the globe.

“Here’s a drug which is potentially pain medication, but which also reverses body temperature, which is dropped under anesthesia,” Patwardhan said. “In one hand you can get two results, both of which are highly desirable under anesthesia.”

“This is where Dr. Patwardhan, who is a practicing anesthesiologist but also a Ph.D. pharmacologist, had this marvelous idea where basically you take the side effect of a drug and use it as the main therapeutic effect,” Porreca said.

The adverse side effects of the TRPV1 drug which raised body temperature could now potentially be used to reverse hypothermia during surgery.

RELATED: Green means go: Emerald light a natural painkiller

Patients suffer from hypothermia in the operating room for two main reasons.

During surgery, incisions in the skin can result in large areas of the patient’s body being exposed, which can drop body temperature, Patwardhan said. Anesthetic gasses can also contribute to hypothermia.

Some of the dangers associated with low body temperature in patients include increased infections and bleeding, as well as shivering and poor wound healing in the postoperative period, Patwardhan said.

Currently, the methods of preventing hypothermia in the operating room are limited.

One way of warming the patient during surgery is keeping the operating room very hot, which is uncomfortable for the surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists who may need to work in the room for long periods of time, Porreca said.

Another option is to wrap the patient in blankets, Patwardhan said. This isn’t always effective, especially during surgeries where there are multiple wounds or a large area of the body is being operated on since the blankets cannot be placed over the incisions.

The necessity for a solution to this problem, combined with the limits of the existing methods, led Patwardhan to search for a more effective treatment.

“As an anesthesiologist, this is what I fight every day,” Patwardhan said.

One of the major benefits of using TRPV1 to prevent hypothermia is its potential to reduce the need for opioids post-surgery.

While working with rat models, Patwardhan said they discovered that the rats who received the drug during anesthesia didn’t require as many opioids to deal with pain after surgery.

Other than a potential decrease in opioid use in the post-operative period, this medication could have several other benefits.

“It would help to minimize pain, get the patient out of the recovery room faster, and maybe decrease the time of wound healing, all of these could be big advantages,” Porreca said.

Currently, the TRPV1 medication has only been tested with rat models.

Before the medication can be used in humans, it needs to pass through a series of toxicology tests and clinical trials to ensure its safety, Porreca said. The drug would only be applied in a highly-controlled setting under the supervision of anesthesiologists.

Both researchers remain optimistic this medication will revolutionize the way anesthesia-induced hypothermia is treated.

“There’s a great opportunity to really improve the way the patients are being treated and improve their outcome from surgery,” Porreca said. “So that’s what we’re hoping, that we can really impact how these procedures are done and the positive outcome in patients.”

Patwardhan and Porreca’s start-up business, Catalina Pharma, is conducting this research in partnership with the UA.

Follow Hannah on Twitter.