On the campaign trail, Donald Trump promised to deport the 11 million-some undocumented immigrants living in the United States. At his 100-day mark, he still has yet to fulfill those promises.

On January 25, he signed an executive order meant to increase Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s capacity to arrest undocumented immigrants who enter the United States illegally.

Within weeks of his inauguration, immigration arrests rose 32.6 percent, according to The Washington Post. Arrests included not only immigrants with criminal records, but also those who were otherwise law-abiding.

Trump’s early intentions for immigration reform was primarily limited to arrests and deportations and deportations, reexamining Obama administration programs such as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and, of course, building a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border.

DACA is a policy created by Obama that began in June 2012 that protects undocumented immigrants who meet certain criteria such as entering the country before the age of 16 and not being convicted of any significant misdemeanors or felonies. These protections include relief from deportation and the granting of a Social Security number and a work permit. More than 750,000 undocumented immigrants are currently protected by this policy.

However, Trump expressed mixed feelings for the so-called “Dreamers” protected under DACA when he spoke at a press conference on February 16, 2017.

“DACA is a very, very difficult subject for me… you have these incredible kids, in many cases not in all cases,” Trump said. “In some of the cases they’re having DACA and they’re gang members and they’re drug dealers, too… The DACA situation is a very difficult thing for me as I love these kids, I love kids, I have kids and grandkids and I find it very, very hard doing what the law says exactly to do and, you know, the law is rough. It’s rough, very, very rough.”

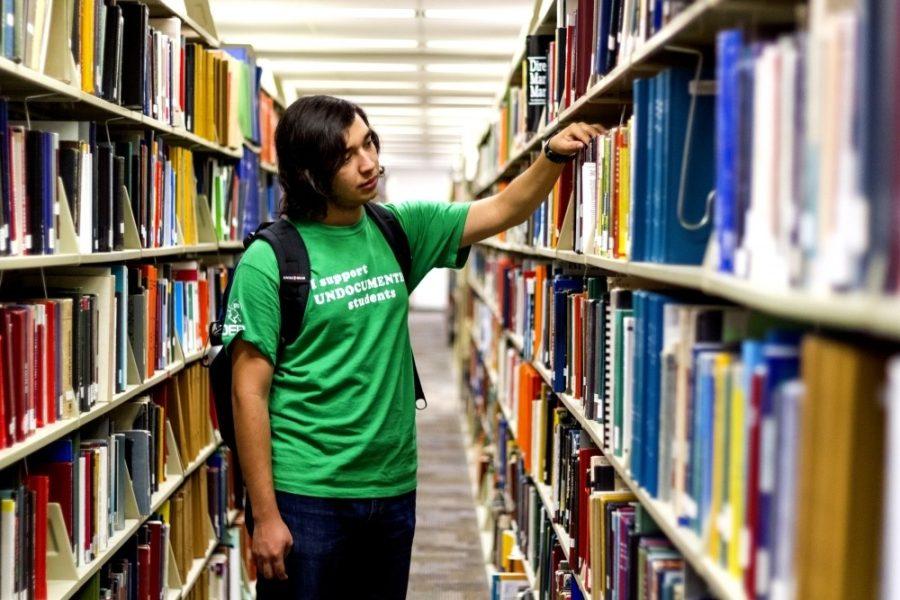

Noemí Salazar Mata, a junior studying journalism and Spanish for translation, came to the United States in 1995, when she was one year old. She and her brother, who was eight months old at the time of immigration, applied and received DACA status in 2012.

Before coming to the UA, she was at Pima for three years because she couldn’t move on.

“In order for me to go to the U of A I had to be international,” she said. “I couldn’t be international because I didn’t have a student visa, so it was impossible. And I couldn’t be out of state because I wasn’t a resident, so I had to wait.”

Another pre-DACA issue included the tuition rate immigrants had to pay. Through an organization called Scholarships AZ, a United We Dream affiliate, DACA students fought to change Arizona Board of Regents policies and won in-state tuition at Pima Community College in 2013 and public universities in 2015.

However, due to other policies set forth by the ABOR, some DACA students feel like the university has not taken their needs into consideration.

“The U of A has kind of set us aside,” political science freshman Ana Laura Mendoza said. “Even though we’re students who are paying, I think that they haven’t really made us feel like students.”

An additional consideration for the university is another policy created by the January 25th executive order, which declared sanctuary jurisdictions across the United States unlawful, citing them as causing “immeasurable harm to the American people and to the very fabric of our Republic.” If the university were to declare sanctuary status for DACA recipients, the federal funding for it could dry up.

UA President Ann Weaver Hart pointed out in a support statement on November 24, 2016 that the university does protect DACA students without having to declare sanctuary status, because as students they are protected under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA, which prevents the sharing of student information. Also, beginning in August 2016, the Immigrant Student Resource Center was created and is funded by student fees.

“Our support for them is unequivocal… The University of Arizona has welcomed and provided DACA students with all the support we can within our authority,” Hart said.

Despite those efforts, DACA students worked together with the National Immigration Law Center and came up with nine policies that universities could do within their jurisdiction, such as not allowing Border Patrol officers on campus, having “Know Your Rights” resources for families, and creating a safe space for students and their families.

“Although President Hart has come out with a support statement, it’s just words that are not followed up by actions, and I think that students now more than ever need actions to defend them rather than pretty words,” Mendoza said.

“At the end of the day, sanctuary is just a title that you use to make a statement that this is a safe area,” she added. “It’s not so much as a title as it is implementing actual policies that would guarantee students a safe place, which I think every student is entitled to regardless of status.”

The Immigrant Student Resource Center cited by Hart is run by eight students and a grad assistant and primarily focuses on two functions: providing resources to students and training to faculty and staff.

Mira Patel, who serves as a College Navigator, indicated that the center has served its community well.

“Before, I had never really met anyone who was [either] undocumented or documented, which made me feel more isolated,” she said. “So I think having a place like this has been very helpful.”

RELATED: Law professors give advice following Trump’s immigration orders

According to Mira Patel, at least half of the 70 DACA students on campus have visited to facilitate its resources.

The biggest fear that many DACA students have is that of family separation subsequent to their parents getting deported.

“With the raids going on, you never know if you’re going to go home to your parents, if they’re going to be there or not,” Mata said.” Or if they leave the house and they get stopped or pulled over or detained or deported, that’s what scares me.”

If someone is arrested by ICE, the Tucson community of immigrants and allies will rally to get them free, sending letters and calling the ICE to let them know that they are not criminals, they have US citizen children, they work, they contribute and pay taxes, according to Mata.

This alliance and unity among the community is a positive consequence Laura sees as a result of the Trump administration.

“[The new administration] was a wake-up call, a cold wake-up call, but it’s definitely there and it’s caused a lot of movement,” Mendoza said. “It’s shown an uprising of resistance, not being submissive and not conforming to what they’re doing.”

There is a lot of confusion surrounding the future of DACA under the Trump administration.

“Even though he says DACA will not be affected, I feel like there’s always that possibility,” Mira Patel said. “Also, even if it’s not revoked, what does that mean for my family, or if there’s nothing beyond DACA, how do I progress in this country?”

Mendoza agrees.

“[It’s] almost like a limbo,” she said. “You’re not in a position where DACA is revoked and your status is now undocumented, but then again you don’t know if it’s truly going to stay or if the next day it’s going to be eliminated.”

That limbo idea is perpetuated by the April 18 deportation of Juan Manuel Montes, a young man who was sent back to Mexico even though he should have been protected by DACA, which would make his the first case of its kind.

“It’s just something I’ve seen happening with this new administration, how they’ve just… instead of actually helping and taking steps, their only solution is to deport,” Laura said.

Patel said she does not regret being a DACA student because it’s helped her become all of who she is now and strengthen her sense of identity— one that would be totally different if she weren’t. She’s more informed on pertinent issues and is proud of being born in Mexico. To Mata, her origin shouldn’t be the issue, it’s the rhetoric and dialogue.

“I don’t think a number and some documents should determine if I can stay here,” Mata said. “You’re allowed to have your human rights, your social rights. A paper and a number, to me, doesn’t mean anything.”

Follow Rocky Baier on Twitter.