Jacob bowed on one knee waiting for the angel to bless him as an observant yellow-green chicken appeared to float weightlessly overhead. Why is there a floating chicken, you might ask? This question kick-started Friday morning’s art therapy session.

The New York-based model of Memories in the Making made its way to Arizona, providing an outlet for transparency and support for those within the Alzheimer’s disease and dementia community.

Marc Chagall’s 1967 lithograph of “The Fight of Jacob and the Angel,” currently on exhibit at The Tucson Museum of Art, was viewed by the participants from the program, coordinated by the Desert Southwest Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

Chagall’s painting shows the angel’s arm crooked above Jacob’s head. Similarly, each caregiver rested their hands on the shoulders of their loved one.

The image of the floating chicken triggered laughter echoing in the early hours of the museum when many recalled childhood memories of growing up on ranches and learning to slaughter chickens — sometimes resulting in bleakly humorous, failed attempts.

Kelly Raach, regional director of the Alzheimer’s Association in Tucson said the organization aims to advocate for an initiative to provide research and resources for those diagnosed with Alzheimers disease, as well as their caregivers.

Alzheimer’s disease starts in the hippocampus, located in the temporal lobes of the brain, progressively attacking different areas and shutting down the individual’s body.

“Some people may die from other complications like pneumonia or failure to thrive,” Raach said, “but the reality is their disease causes them to progress to that point.”

Mary Pittinger, a Tucson Museum of Art volunteer, said she hopes the sense of community provided by MIM will draw others out of living in secrecy and shadows due to social stigmas surrounding the disease.

“Sometimes, people want to hide it or are ashamed of it,” Pittinger said.

This reaction can quickly turn caregiving into isolation, as individuals living with the disease tend to withdraw from social events that create feelings of anxiety and unease.

The MIM program creates new ways for families with loved ones living with Alzheimer’s disease to communicate and express themselves in safe settings.

“If you look around this room, everyone is talking with each other and laughing and are engaged in a new way,” Raach said.

Pittinger worked in memory care units, seeing firsthand the benefits of art and social interaction. Some individuals experience great difficulty in putting sentences together, but when given a microphone and headphones with music playing, they can sing along.

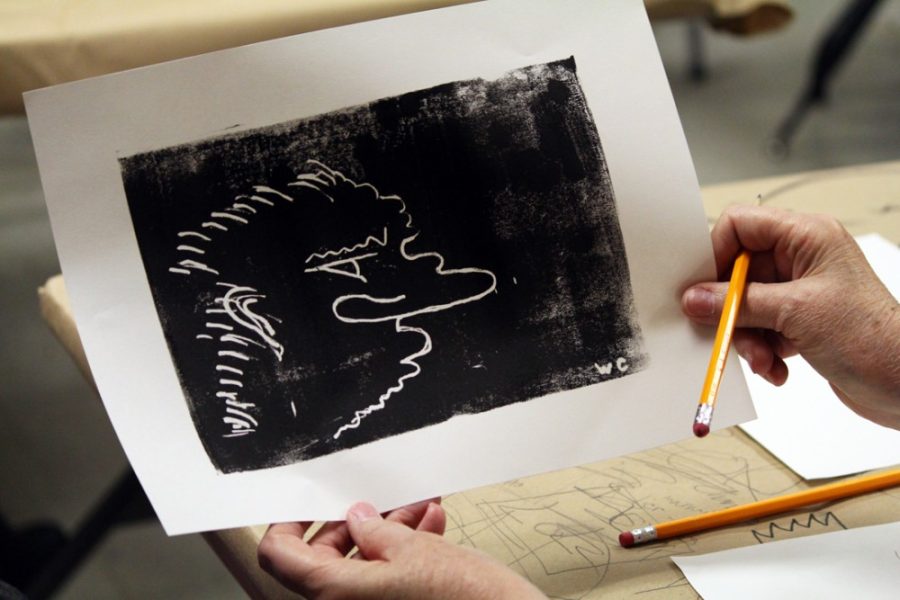

Wayne Collins sat beside his wife, Peggy Collins, as they completed a lithograph-inspired project created by artist Susan Kay Johnson. Wayne Collins’ deep voice described a rich life filled with stories of joining the Coast Guard and working as a BBC stringer in the South Pacific; his career as the face of broadcast news in post World War II Honolulu; and working with Edward R. Murrow before retiring from the UA’s Environmental Research Lab.

Peggy Collins proudly finished each story her husband began telling at his request. As Peggy Collins described how beneficial MIM is for caregivers like herself, Wayne Collins interjected and said he gets to attend when he behaves. The corner of his mouth twitched up in a smile, and Peggy Collins shook her head, smiling.

Chagall’s painting of Jacob and the Angel wresting isn’t so dissimilar with the daily battle to find balance in one’s life, a constant search for relief after a life-changing diagnosis.

Each person living with the disease in attendance had someone battling through this journey with them and an organization advocating on their behalf.

_______________

Follow Anna Mae Ludlum on Twitter.