Last week marked the passing of 399 years since William Shakespeare, writer of two epic poems, 154 sonnets and 38 plays, who is quoted like the final authority on any subject and circumstance, died at 52.

His writing is almost biblical because his epic stories never shied away from the rawness of human nature easily fraught with hatred, love and unbridled wants and the moral laws that inevitably come into play.

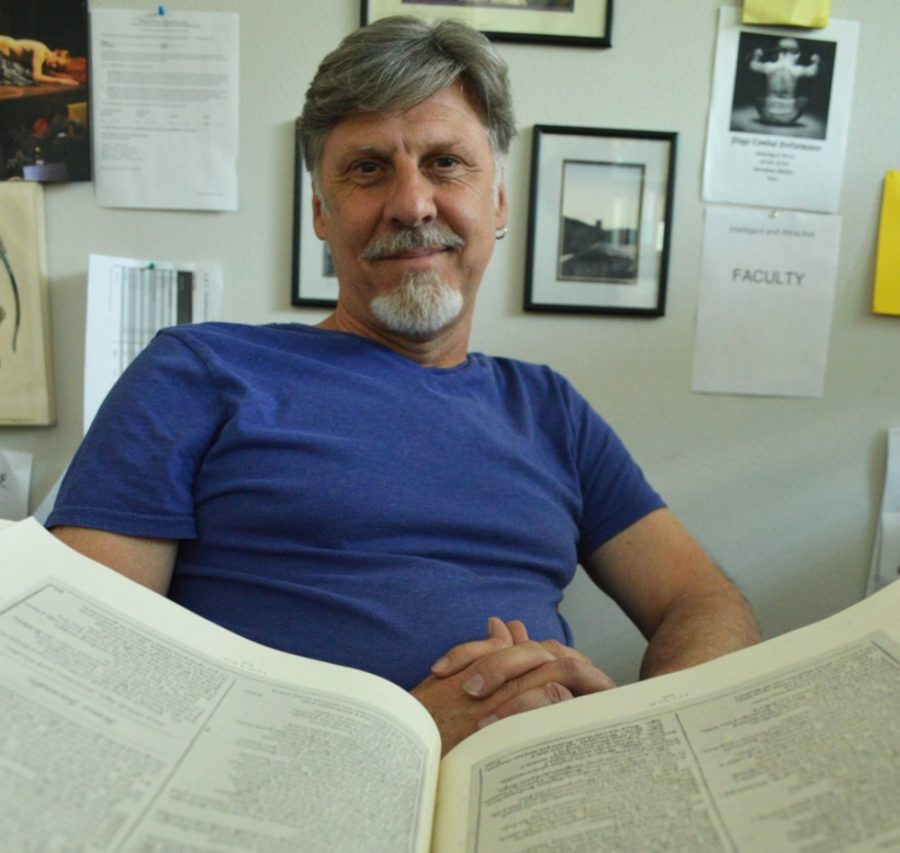

“He’s given us — through poetry — concrete ways of understanding things,” said Brent Gibbs, Arizona Repertory Theatre artistic director.

Despite these universal themes, Shakespeare has been trapped in the genre of classic literature, used and abused by politicians and even middleweight boxer Jake LaMotta, all quoting him in an effort to rebrand their image and sound wise and credible — as if Shakespeare would have approved them and their platform.

By the 20th century, Shakespeare was no longer deemed the writer for the everyman, instead being cast as pretentious and inaccessible.

Chris Okawa, a musical theatre senior, proved himself adept in bringing the words of Shakespeare’s “Othello” to life under Gibb’s insightful direction, with a commitment to do justice to Shakespeare’s writing.

Without losing any poetic language, these two men succeeded in reminding their audience what it must have been like to see this production when it was contemporary writing.

“Shakespeare gives you everything you need, but you have to relax into it,” Gibbs said. “Don’t fear to realize that just because something isn’t easy, doesn’t mean something isn’t worthwhile.”

Okawa acknowledged he struggled with Shakespeare’s language, like most people, but with the enthusiasm of his high school theater teacher, he gained a deeper appreciation of the bard.

“There is a whole thing about haberdashery in ‘The Taming of the Shrew,’ and I was like, ‘That’s not even a real thing anymore,’” Okawa said. “Then I drove past, the other day, Heavenly Hats and Haberdashery in Phoenix.”

Gibbs was also introduced to Shakespeare in high school when assigned to adapt a scene from “Macbeth,” replacing the Scotsman’s murder weapon with poisoned tater tots. Deeply passionate in making Shakespeare accessible and humanizing the man put on a pedestal, Gibbs teaches his students how everyday lexicon, ideas and concepts originated with Shakespeare in an effort to minimize the distance between modern society and the timeless writer.

“I connect with the plays, and I connect more and more deeply with them the more I study them and the more I teach them,” said renowned Shakespeare scholar and UA English professor Frederick Keifer of the time and patience required to guide his students to find joy in Shakespeare’s work.

The difficulty can be found in Shakespeare’s uncomfortably relentless need to make his audience question what they believe to be true when based on experiences, the age in which you live, the place you reside and the influence of those around you.

“What he always does is show you this is the price you pay when you do stuff like that,” Gibbs said, describing Othello’s abuse of the innocent after falling prey to a lie cloaked as truth. “There is a moral ramification for it.”

Of course, his writing often reveals he was a man of his era, seen in the caricatured Jewish money-lender Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice.”

Despite this, for Okawa, it’s the many aphorisms in his writing that illuminate Shakespeare’s value.

“To me, those are just direct eternal truths,” Okawa said. “If you can retain one of those from attending a production, I would say that’s worth the value of a ticket.”

Despite those truths, Shakespeare’s job was to entertain. Quoting “Hamlet,” Keifer’s favorite play, he succinctly concluded why Shakespeare’s work remains resilient: “The play’s the thing.”

_______________

Follow Anna Mae Ludlum on Twitter.