At 4:30 a.m. last August, Brian Seastone received a life-changing phone call. The voice on the other end of the line informed the University of Arizona chief of police that Woman-Ochre, a painting stolen from the UA Museum of Art over 30 years ago, had been recovered at a location just three hours away.

“I woke up really quick after that,” Seastone said. “I think there was a smile that broke out ear-to-ear. I don’t think I had ever had one quite that big. All I could say to myself was, ‘It’s finally coming home.’”

RELATED: Bookstore is the spine of campus

The day after Thanksgiving, 1985, a nameless pair — a man and a woman in a headscarf — entered the UAMA as it opened its doors. The woman chatted with the security guard while her partner went upstairs. No more than fifteen minutes later, they left in a hurry with the painting rolled up beneath a coat.

They escaped in a copper-colored car and disappeared with the painting.

It was not until after the fact that the museum staff discovered Willem de Kooning’s “Woman-Ochre” to be missing, cut from its frame.

Seastone, who had been a lead investigator on the case, and the UAPD immediately called in a large team —local agencies, the FBI and even Interpol, due to the very real chance that the piece had left or would leave the country — to investigate. The work did not last long.

“We did as much as we could for a week,” Seastone said. “[The case] didn’t have any leads; All we had was this [copper] colored car that was seen leaving the area. It was really just something out of the movies and it went cold very very quickly. Sometimes you just can’t connect all the dots.”

No fingerprints were left behind, no trace evidence. All the investigators had were a description of the thieves and a car that ultimately led nowhere.

“Woman-Ochre” is valued at approximately $100 million, but according to UAMA Curator of Exhibitions Olivia Miller, de Kooning paintings are not a rarity.

“It’s not like [de Kooning paintings are] rare,” Miller said. “He lived into his 90’s, so there are a lot of surviving de Kooning paintings. It’s not the same as Vermeer, who only has 30 paintings in the world.”

“Woman-Ochre” is oil on canvas, painted between 1954 and 1955. It depicts a highly abstracted, gestural woman with broad shoulders, small legs and pronounced breasts. While the brush strokes are heavy and the figure is darkly lined with black, the painting has a lot of color — orange, yellow, turquoise, magenta.

According to Miller, “Woman-Ochre” is, like many of de Kooning’s paintings, purposefully ambiguous.

“De Kooning painted a lot of women; he returned time and again to the female figure,” Miller said. “His work has often been compared to the Venus Figurines of the old stone age.”

De Kooning lived in a post-World War II era, when the center of the art world had moved house from Paris to New York City. Miller believes this fragile timeline may be why de Kooning’s work is valued so highly.

RELATED: UA cultural centers embrace campus diversity

Miller said that de Kooning stands apart from other abstract expressionists because, while many of them created purely abstract artwork, de Kooning found a way to fuse abstraction and representational art in a way that was eye-catching.

“De Kooning is just a technically brilliant artist,” Miller said. “His style is truly, uniquely his own.”

However valuable, though, “Woman-Ochre” remained lost.

There were theories. According to Seastone, some of these included two male perpetrators, one of them dressed as a woman. Miller imagined the painting made its way to Saudi Arabia or another far-away land. Without any leads, the investigation largely ceased, but Seastone himself never lost hope.

“I didn’t know when, but there was just this gut feeling I had that someday it would be home,” Seastone said.

The museum never forgot the tragedy, instead transforming it into a learning opportunity. According to Miller, UA professor of art and anthropology Irene Romano teaches a regular class on art crime and takes her class to the museum every year to view the empty canvas.

It wasn’t until Lauren Rabb, the former curator of art at the UAMA, began doing research into art crime files at the museum nearly 30 years later that the case was put back into the limelight.

“[Rabb] was the one who really got us all excited about the painting again,” Miller said.

Rabb contacted the FBI and asked if they were still working on the case. In 2015, the UAMA commemorated the 30th anniversary of the theft, reminding the public to keep searching.

A little over a year and a half later, “Woman-Ochre” was found at an estate sale in New Mexico, in the home of the late Jerome and Rita Alter, a retired music teacher and pathologist from New York, respectively.

“Of course it’s only three hours away,” Miller said.

David Van Auker, the owner of Manzanita Ridge Furniture and Antiques in Silver City, New Mexico, bought the painting for $200. When Van Auker put the painting on display, a few customers brought the piece’s value to attention.

After doing some research into “Woman-Ochre” and the story of it’s theft, Van Auker promptly contacted the UAMA. Van Auker affirmed he only hoped to safely return the painting to its rightful home.

“Art is found by accident a lot, either somebody dies, it shows up on the black market somewhere, something. That’s what happened in this case,” Seastone said.

Miller was speaking with UAMA Interim Director and Chief Archivist Jill McCleary when the museum got the call from Van Auker. She overheard a conversation over walkie-talkie between a security guard and Jim Kushner, the head of security.

“Jim, I have a man on the line that says he has our stolen painting,” the security guard said.

Miller and McCleary stopped what they were doing. Miller actively tried to keep herself together, not giving in to false hope.

Van Auker said that the painting had creases on the canvas as if it had been rolled up. Miller was ecstatic.

“Are we going to remember this moment for the rest of our lives?” McCleary asked.

McCleary immediately texted Kristen Schmidt, the UAMA registrar, while she was in Germany retrieving a painting loaned to a museum. It was late, Schmidt having just finished eating in the airport cafeteria.

“Here I am in an airport motel at midnight,” Schmidt said, “screaming about the FBI and the UAPD.”

While Schmidt took the long flight from Germany to Tucson, other museum staff members gratefully retrieved the painting in a crate from Van Auker in Silver City. Yet, when the painting had finally made it home, the crate went unopened.

“When travelling artwork, when we get it to its destination, we don’t open it right away,” Schmidt said. “We let it acclimate. Like when you buy a fish and you set it in a little bag in the aquarium so that water slowly turns to the same temperature so you don’t shock the fish. It’s the same with artwork. We didn’t want to shock the painting with the environment.”

The crate was not opened for several days.

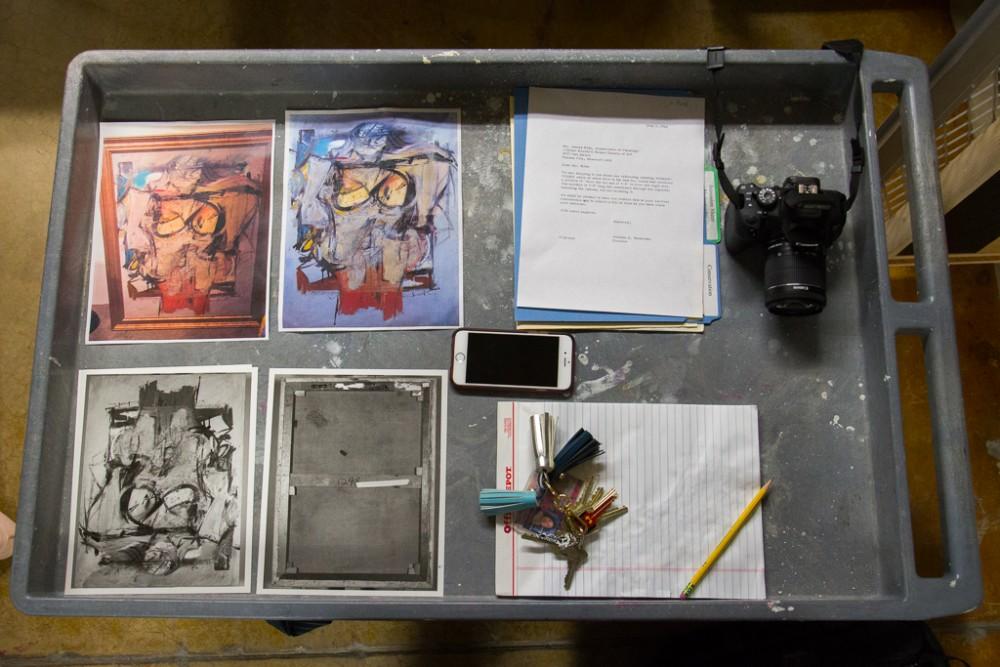

Nancy Odegaard, a renowned objects conservator at the Arizona State Museum, was invited to inspect and authenticate the painting. Meanwhile, McCleary was documenting everything.

“We all knew it was the painting, but obviously we couldn’t just say we knew it was the painting,” Miller said. “You have to have people back you up on that.”

When Odegaard finally unpacked “Woman-Ochre,” she first inspected it facedown, prolonging the wait by what Schmidt referred to as “agonizing minutes.”

Schmidt had been skeptical, at first, but no longer.

“I think I was definitely a believer by time we opened the crate,” Schmidt said. “If you can imagine the greatest thing that could ever happen to you in your career, that would be that moment.”

RELATED: Get to know Tucson’s music scene

Odegaard inspected the painting thoroughly and non-invasively, using black lights and raking light to check its condition. Then the staff uncovered the original frame to see if the painting matched the empty canvas.

“The only proof we really needed to prove it was our painting was to lay it on top of the fragment. Our staff has always held on to the original frame and the original stretcher from which the canvas was cut,” Miller said. “We layed in on top. The cut lines perfectly matched; there were paint strokes that had been sliced through so you could match it. It was like a puzzle. I will never forget it as long as I live.”

The painting is still incredibly fragile, according to Miller. The museum took “thousands” of photos, Schmidt said, and packed the painting away in a drawer, away from prying eyes and the harshness of the environment.

In the year since the painting’s recovery, the FBI case is still open, meaning “Woman-Ochre” is still considered evidence. Thus, the painting cannot be repaired or put on display.

“We’re really at a standstill until the FBI closes the case,” Miller said.

For now, the staff has been conducting conservation science to determine the painting’s damage and what steps the conservator will need to take in future repairs, endeavors in which the museum staff has received much help from both the Arizona State Museum and doctoral students.

RELATED: Centennial Hall

“This painting has been gone for 30 years and it has missed out on 30 years of scholarship,” Miller said. “The best we can do is turn this horrible theft into a learning opportunity.”

There have been celebrations in Tucson and in Silver City and UAMA has set up the De Kooning Fund to raise money for the continued care of “Woman-Ochre.”

The museum staff has been exploring the possibility of putting the painting on view before its repairs. Even after repairs, though, “Woman-Ochre” will likely remain changed forever.

“It will never be the same. The damage that it’s undergone; that damage will always be there. Its history will always be there. There are layers of meaning that were never there before. It will never escape that,” Schmidt said. “But will it go up on the wall and have the same effect on visitors and the study of art history? I have hope that it will. I have hope that you would be able to see it up on a wall and not see where we had to sew it back together.”

The staff has remained optimistic that the painting’s case will be closed soon. However, according to Schmidt, investigators have been “a month away” from solving the case for around a year.

Theories are still piling up. The potential involvement of the Alters, who were in Tucson visiting family the day of the theft, could possibly answer many questions, while opening up many more.

“If this painting could talk,” Seastone said, “she has an incredible story to tell.”

Follow The Daily Wildcat on Twitter