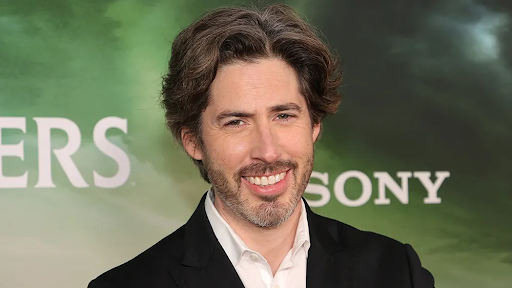

On Friday, March 25, UA’s College of Social & Behavioral Sciences sponsored a lecture entitled “A Conversation on Privacy,” in which privacy hotshots Edward Snowden (who participated via video from an undisclosed location in Russia); Dr. Noam Chomsky, a linguistics and philosophy professor at MIT; and Glenn Greenwald, a famous lawyer and journalist, discussed cyber security in the digital age.

The line to get in Centennial Hall’s front doors curved out along the sidewalk as eager students, faculty and Tucson community members awaited their turn to have their bags searched and find their seats. Once everyone had settled in, the moderator and CEO of the Center for Democracy & Technology, Nuala O’Connor, steered the discussion towards the power of the press as a governmental check. The opening segment revolved around the whistle Snowden blew: the truth about the National Security Administration’s (NSA) PRISM program, which was revealed to have been secretly collecting private communications since 2007.

All three panelists agreed that privacy is a right, whether the foundation of that right goes back to the requirement for probable cause in the constitution, historical Supreme Court rulings, or the fundamental right to one’s self. The panelists also agreed that the U.S. government had not only overstepped its constitutional authority, but was beginning to “jog” with the PRISM surveillance program.

But, that begs the question: what exactly is privacy?

Chomsky suggested that privacy is the ability to be alone, without the pressures of society, to think and form one’s own opinions. He noted that this space is integral to free thought and individualism. Greenwald added that people act differently if they think they are being watched—if they know they are being observed, they are far more likely to act in lockstep with societal expectations. The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist referenced George Orwell’s “1984,” one of the most famous novels on governmental intrusion gone awry, noting that in the book’s fictional world the government did not constantly analyze each citizen, although they had that capability. Similar to data collection with PRISM, “1984’s” “Big Brother” could watch citizens at any time, but there was no way to know whether one was being monitored. The mere threat of surveillance at some point in time was enough to make citizens act as if they were being watched constantly. That is the threat presented by programs that indiscriminately collect our private communications.

But when does security become more important than privacy? And if less privacy means more security, is that a worthy tradeoff?

If larger surveillance means a dramatic drop in the number of violent attacks by extremist groups, citizens may happily give up their right to a private Internet conversation. But, more invasive and widespread data collection does not necessarily mean better information. Not one panelist objected to targeted surveillance of terrorist suspects or advocated publishing the names of every individual under surveillance. Instead, they argued that the sheer mass of data collection “unconstitutionally” done by the government was too extensive and that more data collection was not addressing the root causes of insecurity. Snowden said that the data collected by the NSA did not dramatically drop the number of terrorist attacks, although he did note times where sexually explicit photos from private citizens were intercepted and passed around the NSA, times where the data was used for monitoring of human rights organizations like Amnesty International, and instances when they monitored the porn-watching habits of non-violent non-terrorist radical thinkers.

When O’Connor brought up the recent tragic attacks in Brussels and San Bernardino, the panelists suggested that increased surveillance is not the answer to preventing future attacks. Greenwald pointed out that in all of the hubbub following the Brussels attacks, he had not seen a single TV reporter ask why the attacks had happened. Not one person asked why people were willing to trade their lives to destroy westerners, particularly Americans.

There are other democratic, non-Muslim countries that are not the focus of terrorist attacks. He reasoned that the explanation lies in a 2004 report issued by the Defense Science Board Task Force, which noted the root cause of terrorism is not a loathing of America’s democracy or religious preferences. It is based on the perception of the U.S. in the Arab world, which is overwhelmingly negative because of past actions to keep tyrannical regimes in power, one-sided support for Israel, and U.S. occupation in the Middle East. This public attitude was cited as one of the most important “underlying sources of threats to America’s national security.”

Both Greenwald and Chomsky argued that if we want to stop terrorism the answer is not to broaden surveillance programs, but rather to lessen the desire for terrorism and address the root causes of what drives people to violence.

Judging by the timing of audience applause and the standing ovation for Edward Snowden, the crowd in Centennial Hall on Friday was largely pro-privacy. And yet they all allowed their private bags to be searched on the way into the talk without a fuss. There is clearly a tradeoff between security and individualism; some privacy must be sacrificed to allow the U.S. government to keep Americans safe. That said, citizens should have a say in how much privacy they are willing to trade for security. And if citizens are truly concerned about stopping terrorism, the debate must go beyond privacy.

Follow Julianna Renzi on Twitter.